The Sugar Beet Field

Recalling a long-ago microburst that forced a firm farm landing in Colorado

Aviation has been a major interest in my life since I was a youngster, but I’m not sure where that came from. My dad learned to fly a Piper J-3 Cub in a farmer’s field near our hometown of Haxtun, Colorado, in the early 1950s, but I never knew that until some years later.

Shortly before my 16th birthday, he drove me to the airport in Sterling, about half an hour away, four times for half-hour lessons in a Cessna 120 and 140. After one of those sessions, before the drive home, I overheard him tell my instructor, Ron White, a former military pilot, “He knows what they’re made of all right.” It made a huge impression on me and whetted my appetite for more. However, Dad gave me a choice: either a used car or flight lessons, but not both. The car was the choice because it could be used every day, and flight lessons could be picked up at a later time.

After graduating from high school at 17 in 1956 and attending two years of college at the University of Colorado in Boulder, there was little feeling that anything substantial was being accomplished in the academic world. My parents suggested that I transfer to the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley and pursue a degree in education, as my mother had done in Nebraska. What I had to show for two years at CU, however, was a private pilot certificate earned at the Boulder airport (KBDU).

While at Greeley, flight time accumulated slowly, including getting checked out in a Piper J-3 Cub. From Greeley, I moved to Fort Collins, where I was hired as a French and social studies teacher. Teaching had never even been considered as a career but, in hindsight, it must have been what God had in mind for me because it turned out to be enjoyable and lasted 42 years, including a total of nine in foreign locations—Canada, England, Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands of the western Pacific, and Seoul.

But private flying, as we know it, did not exist in those places. Fort Collins, however, had a small single-runway airport just at the edge of town where a lot of time was spent earning additional licenses and ratings.

At that time, I was attending First Baptist Church, just across the street from my school. One Sunday after a service, a young man about my age approached me and introduced himself as Dana Jeffries, a band teacher with the same school district I was in. He had heard I was a pilot and said he was interested in learning to fly but had not yet been up in a plane. I said we could take a flight together the following Sunday after church so he could see what flight in a small aircraft was like.

I told Dana I could rent a Cessna 172 at the nearby Fort Collins-Loveland airport (KFNL), and since the 172 could carry four people, I said I would invite two others to go along. He agreed and I reserved the 172.

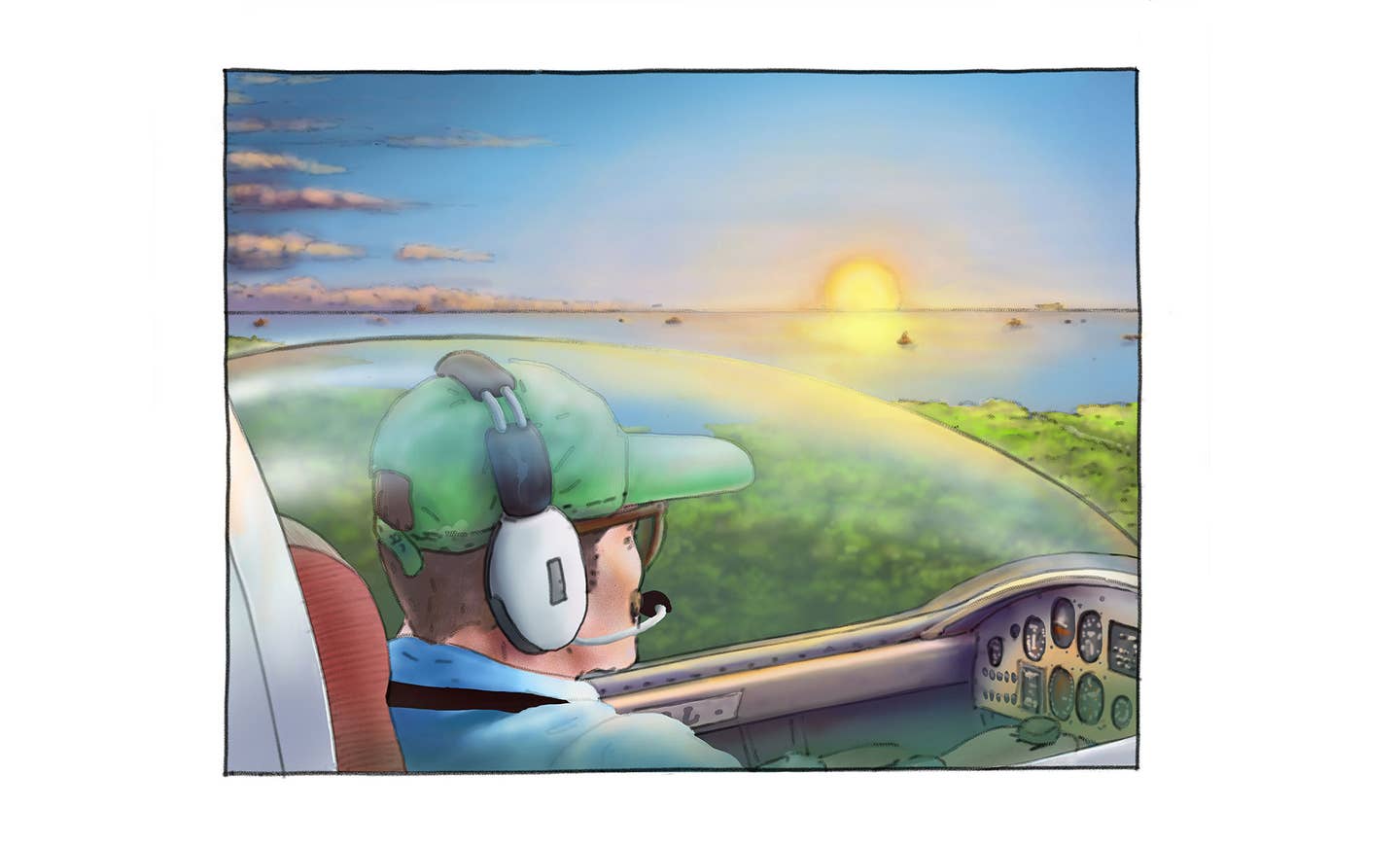

The next Sunday, the day began with a typical clear blue Colorado autumn sky. The airplane was ready, and I first had Dana follow me around it as I did a preflight inspection, pointing out that it was a procedure all careful pilots followed so that all the important items had been checked. We then boarded the plane and, since I wanted Dana to have some control part of the time, I gave him the front right-hand seat, and the other two people got comfortable behind us.

As we taxied to the runway for run-up and departure, I explained what was happening at each step so Dana would feel a bit involved and more at ease. Takeoff was normal and, after gaining some altitude, I helped Dana learn a bit about controlling the plane with some straight-and-level flight, and a few gentle turns as well as climbs and descents as we headed toward the Greeley airport only about 25 miles away. He seemed quite interested and did a good job.

As we neared the Greeley airport, I took control again and pointed out the various steps in making a landing. The four of us spent about 30 minutes looking at the other planes then agreed it was time to start back to the Loveland-Fort Collins airport.

By this time, typical early afternoon clouds were beginning to build along the foothills of the Rocky Mountains immediately west of Fort Collins, and it was quite common to have some occasional downdrafts, as they were all called then, ranging from mild to moderate to severe. I don’t think the term “microburst” even existed at that time.

Because of the possibility of encountering a downdraft, I explained to the passengers that I would use a slightly modified takeoff in which I would hold the plane on the ground a bit longer than normal to gain a little more speed and then pull it up slightly abruptly in case any downdrafts were present, a normal procedure. The takeoff was quite normal, and we began a standard climb, turning slightly westward toward the Fort Collins-Loveland airport.

Soon, I noticed that the Cessna seemed to have stopped climbing and was, in fact, beginning to go down as if a giant hand was pressing on the wing. We had flown into an invisible microburst, and the Cessna was unable to climb but was certainly being forced toward the ground. Since the winds are invisible, there was no way of knowing which way to turn to escape the situation. I had also read too many articles about pilots having engine problems and trying to turn back to the airport from a low altitude with disastrous results, so that option was quickly discarded.

Straight ahead, not too far, was a row of fairly high trees, perpendicular to our flight path, which I knew I could not climb over if the descent rate continued, so that choice was also scrapped. The view out the left window was not any better with a huge junk pile parallel to our line of flight. Trying to land in that spot would only save people later from having to move the wreckage there after the crash.

Looking out Dana’s window on the right revealed what had to be our best chance for a reasonable landing. It looked like a fairly open, flat, harvested sugar beet field, but it had furrows in it running 90 degrees to our line of flight. Sugar beets are a common crop in the Greeley area, and we were now too low to look for other possible landing sites, so I told the passengers to be sure their seat belts were tight, made a quick turn to line up parallel with the furrows, and just a few seconds later we touched down just a bit harder than normal since we were still in the grip of the microburst.

The brakes brought us to a fairly quick stop, the engine was shut down, everyone exited the plane, and nobody suffered even a small scratch, for which I was quite thankful. I don’t recall actually giving God a word of thanks for any part he might have played in the drama, but I like to think he or at least a couple of his angels were present to guarantee a safe outcome.

Immediately, I noticed a car stop at the edge of the field, and the driver jumped out and ran to see if everyone was safe. Strangely enough, I recognized the man as a local Greeley pilot nicknamed “Skipper,” whom I had seen fly aerobatics in the area a time or two. He congratulated me on a good landing and, coming from him, it meant a great deal.

Skipper said he had also been caught in a downdraft a day or two earlier and had been fortunate enough to fly out of it. He was gracious enough to offer us a ride to the airport where our cars were. He was just that kind of a guy, and he corroborated my account of the incident as I told it to the airport manager. The manager said he and a mechanic would drive there and, if they determined the plane was flyable, it would be flown back to the airport, which is what happened.

Because the damage to the landing gear was slight, it was not considered an accident and did not need to be reported to the NTSB, so I never heard another word about it.

Oh, yes, the two passengers in the back seat who were part of this little escapade? Who else but my mom and dad! They did accompany me on other flights later, so I felt they had confidence in my pilot skills.

And Dana? He did take lessons, earned a private pilot certificate, and later was my partner in ownership of two planes, a Cessna 152 and later a Piper Cherokee 180 that we owned for years with no major problems. We flew the Cherokee over much of the U.S., each of us logging PIC time only when actually piloting.

From Fort Collins we flew the Cherokee south to visit Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico, one trip to San Diego via the Grand Canyon to visit my sister and her husband, then a second trip to visit them in Seattle with a little detour into a bit of Canada. Other trips from Fort Collins included Glacier and Yellowstone national parks and a long one to the Florida Keys. Other trips to minor destinations kept the Cherokee quite busy.

Finally, after eight pleasurable years, we sold the Cherokee, with pretty high time on the engine, for the same price we had paid for it.

Now, at 85, I look back with great satisfaction through my several logbooks on many enjoyable adventures and a good partnership with a close friend.

Image: Adobe Stock

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox