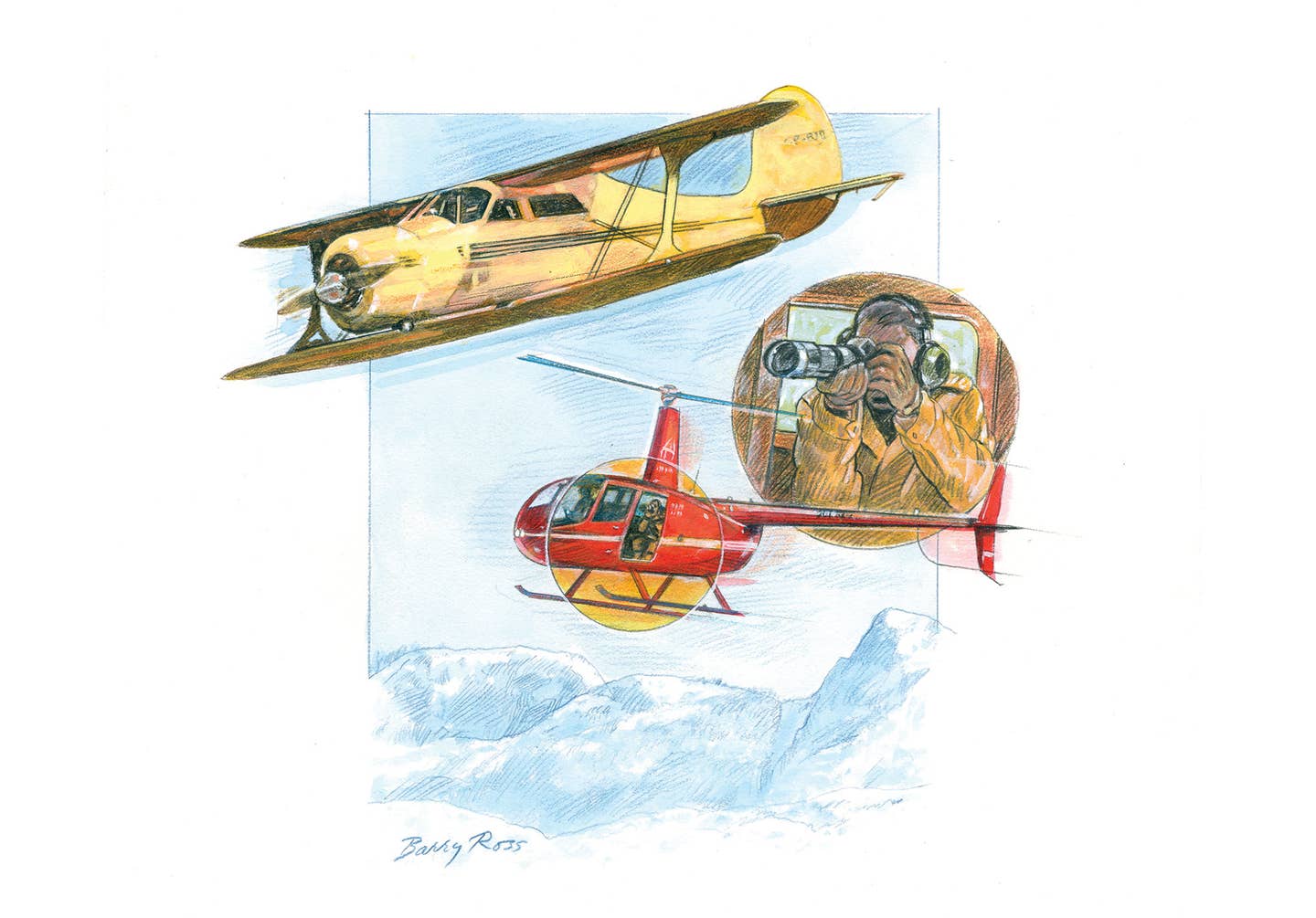

Most of my flying was in the 1960s and ’70s, long before many of you reading this were born, but they were good years.

Though being a pilot had been a dream since childhood, my adult 42-year career was as a teacher of French, primarily in junior and senior high schools both in the U.S. and internationally. Aviation was a very enjoyable pastime from age 17 to 65 or so, and teaching allowed me a lot of time, especially during summer and winter school breaks, for aviation.

Not a bad combination.

Spare time was often spent reading aviation books and magazines or browsing through the aviation-related journal Trade-A-Plane, where I one day came across a very intriguing, very short ad. It read something like, “Pilots wanted. Must have commercial license, 1,000 hours minimum, taildragger and no-radio cross-country time,” and there was a phone number.

That was it. There was nothing about where the job was, what kind of aircraft were involved, and not a word about the pay. It almost made me wonder if it might involve something illegal, but curiosity got the best of me, so I called the number shown.

Hank Koenig answered and said he worked for the Ferry Service Company in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania. I knew that was where Piper had its factory, where all of its planes were manufactured at the time. Some years later, a flood of the nearby Susquehanna River resulted in considerable damage to the factory, and it was decided to move the manufacture of many of Piper’s planes, especially twins, to a new factory in Vero Beach, Florida.

Koening explained that ferry pilots were needed to deliver new planes to their owners across the country. But personally, I prefer the term “delivery pilot.”

Naturally, I was interested and told Koening I had a commercial license, a tailwheel endorsement, and no radio time, but I had only logged about 700 hours. He was apparently satisfied with that or was rather desperate for pilots because, before that initial phone call ended, he had offered me the opportunity to deliver a brand-new Piper Pawnee crop duster/spray plane from Lock Haven to Nogales, Arizona.

That is nearly completely across the U.S., and I had never flown a Pawnee. In fact, I wasn’t real sure I knew what one looked like but, for better or worse, I accepted the job I had not even applied for and was now a part-time delivery pilot.

Things like that make me wonder how much more God works in our lives than we usually think. If someone else had answered that phone, they could have said, “Sorry, you are too far from the minimum flight time required,” and that would have ended the conversation. But Hank was different, he was willing to take a chance on my experience, and it turned into a five-year-long relationship that was far more interesting than I could have imagined.

Since I was single at the time, leaving on a trip on very short notice was not a problem. For the first trip, I flew commercially from Denver to Pittsburgh, then took a Greyhound bus to Lock Haven. On later trips, to save some money, I would take a bus from Fort Collins, Colorado, to Lock Haven, a two-day trip, sleeping on the bus but still an adventure.

For the first trip, Koening introduced me to the Pawnee and showed me the kind of preflight inspection he used. Since there was only one seat, there was no checkout flight. He assumed I knew what I was doing to fly the Pawnee safely, and I appreciated his confidence.

The trip went very well, the key and paperwork were turned over in Nogales to the airport manager, who would give them to the pilot who would come to take the airplane across the border to Mexico, where it would be put to work. The second delivery flight a very short time later, was a repeat—a Pawnee to go to Mexico.

The boyhood dream of being a pilot was coming true.

Now fast-forward to delivery No. 15, another Pawnee to near El Centro, California, also on the Mexican border. But this was a winter flight over Christmas vacation from teaching, and it was a completely different adventure.

Pawnees are made for agricultural summer work, not for winter cross-country trips, so they had no heater, and winter in Pennsylvania and other Northern states can be very cold and nasty, so extra-warm clothing was the order of the day.

It was December 22, my birthday, when I departed Lock Haven. It was also the second shortest day for daylight in the year, so flight time would be limited. Night flights and instrument flights were not allowed on delivery flights for insurance purposes. The weather was marginal but flyable and definitely cold.

Theoretically, it would get warmer as the trip proceeded southwesterly, but the Northern states were firmly in the grip of winter. Later, poor weather grounded this trip for two days.

At the end of the day on December 24, I was only in Bedford, Indiana. At the airport, I explained to the manager what a crop duster was doing flying around in winter, and I asked him about finding a motel for the night. He wouldn’t hear of such a thing, not on Christmas Eve, so he insisted I go home with him and spend the night with his family, which I did and greatly appreciated. Aviation has led me to meet many very fine people. The next morning, he drove me back to the airport, and I was soon on the way again.

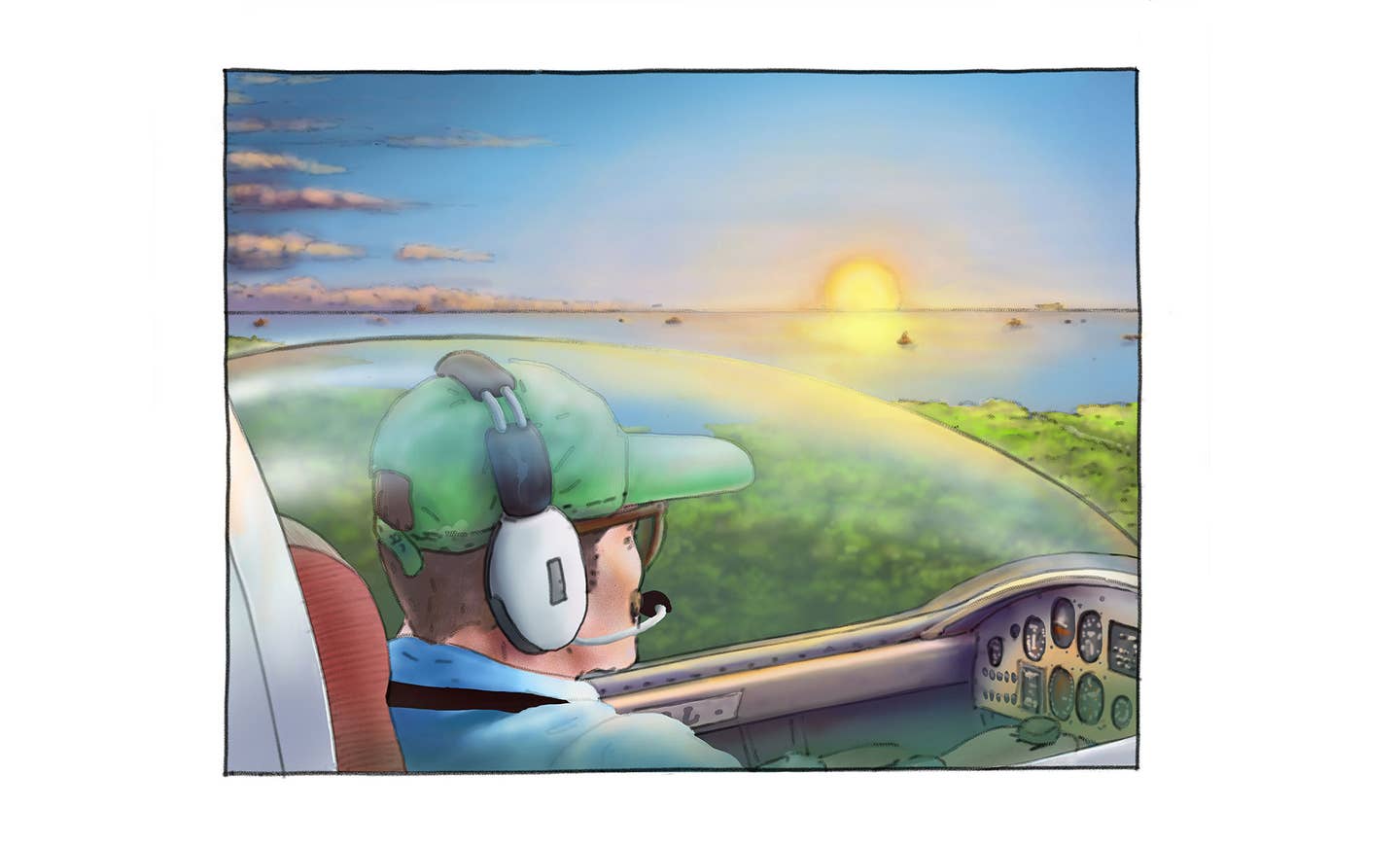

Later, over southern Arizona, it was still quite hazy, and I could see that the haze could possibly become a fog problem, and VFR flight would only be possible at rather low altitudes. Though I was certified for IFR flight, the Pawnee certainly was not equipped for it and insurance prohibited it.

At this point, my concern was growing. There was no fear, but I really didn’t want to make an off-airport landing in the desert where the only terrain around was rough dirt and sand, small and big rocks, cactuses, and sagebrush with not much more flat open space than enough for a helicopter.

So I was preparing mentally to put the airplane down with as little damage as possible to it or myself. It seemed a good time to have a little chat with God to explain the situation and ask for some help. I figured if the plane was not on the ground in the next 15 minutes, I would be aloft with zero visibility.

Within about another minute or so, something appeared directly ahead that was totally out of place and amazed me. I was looking at what appeared to be some dirt roads or streets in a grid-like pattern as if for some housing or commercial development. But there were no buildings at all, no fences or telephone poles or power lines anywhere in my vision, just beautiful straight dirt streets—my own private airport.

I selected one for a runway, flew low alongside it, looking for any obstacles and, seeing none, circled quickly and landed. I doubt that 10 minutes elapsed before a very dense fog rolled in to envelop the area. The weather was fairly warm and all was quiet.

After a sincere “Thank you!” to the Lord, I took a book from my travel bag and made myself comfortable on the wing to read and wait for the fog to clear, which it did in an hour or so. The trip continued, with neither the plane nor myself any worse for wear.

Near Yuma, Arizona, the fog returned, and I’d had enough for the day, so I landed there and explained the situation to the airport manager and left the keys with him. The fog was forecast to last a few days, and it turned out to be the worst occurrence in 50 years. I phoned the plane owner to explain the situation to him, and he was happy to have his plane so close and in perfect condition.

On the bus back to Colorado, reflecting on the trip, there was a good feeling that the mission had been completed in a professional manner. Koening sent me a check for the entire trip, which was much appreciated.

A truly good pilot will put safety before ego and make correct decisions that will allow him and his passengers to fly again.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox