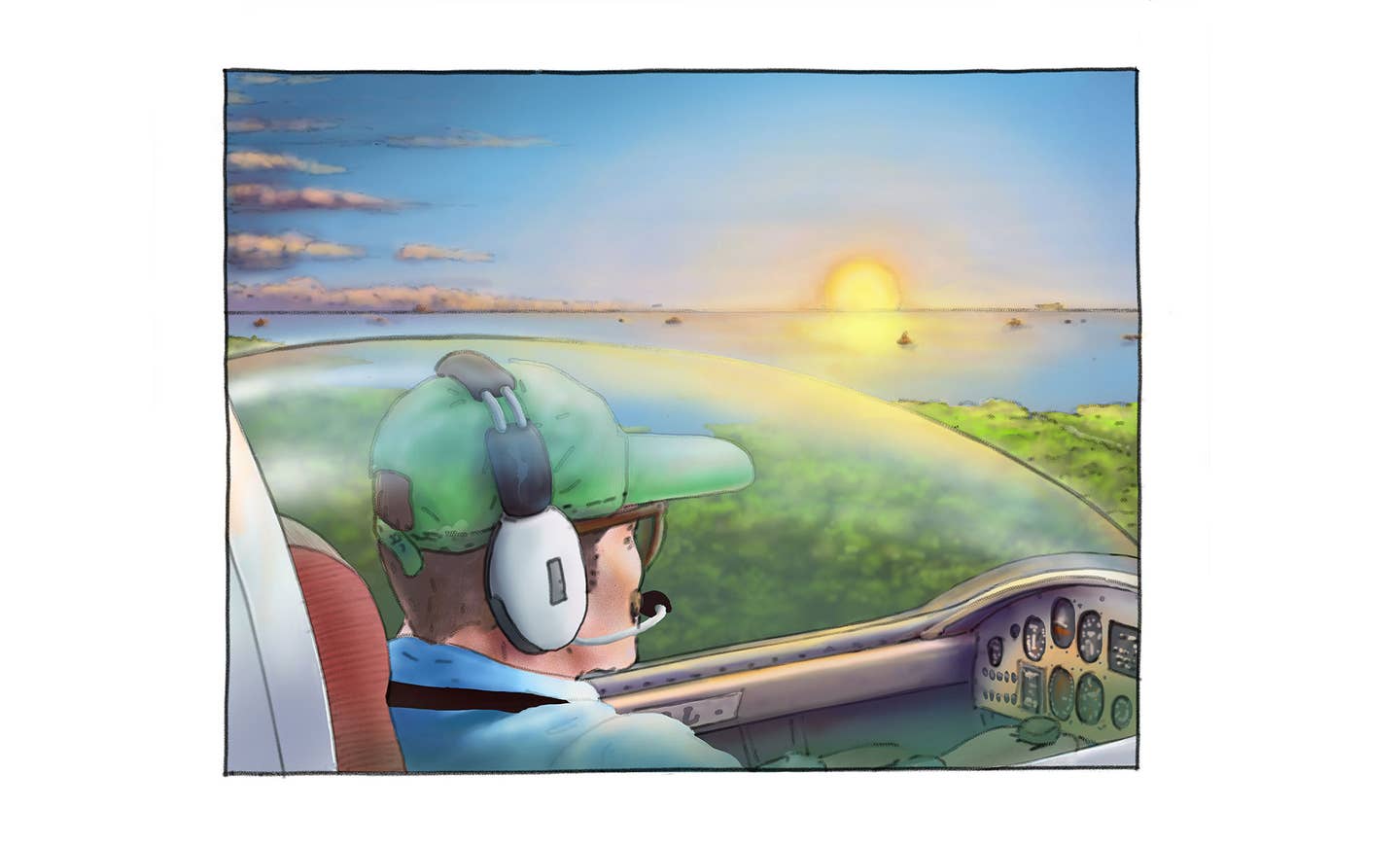

Silent Flight

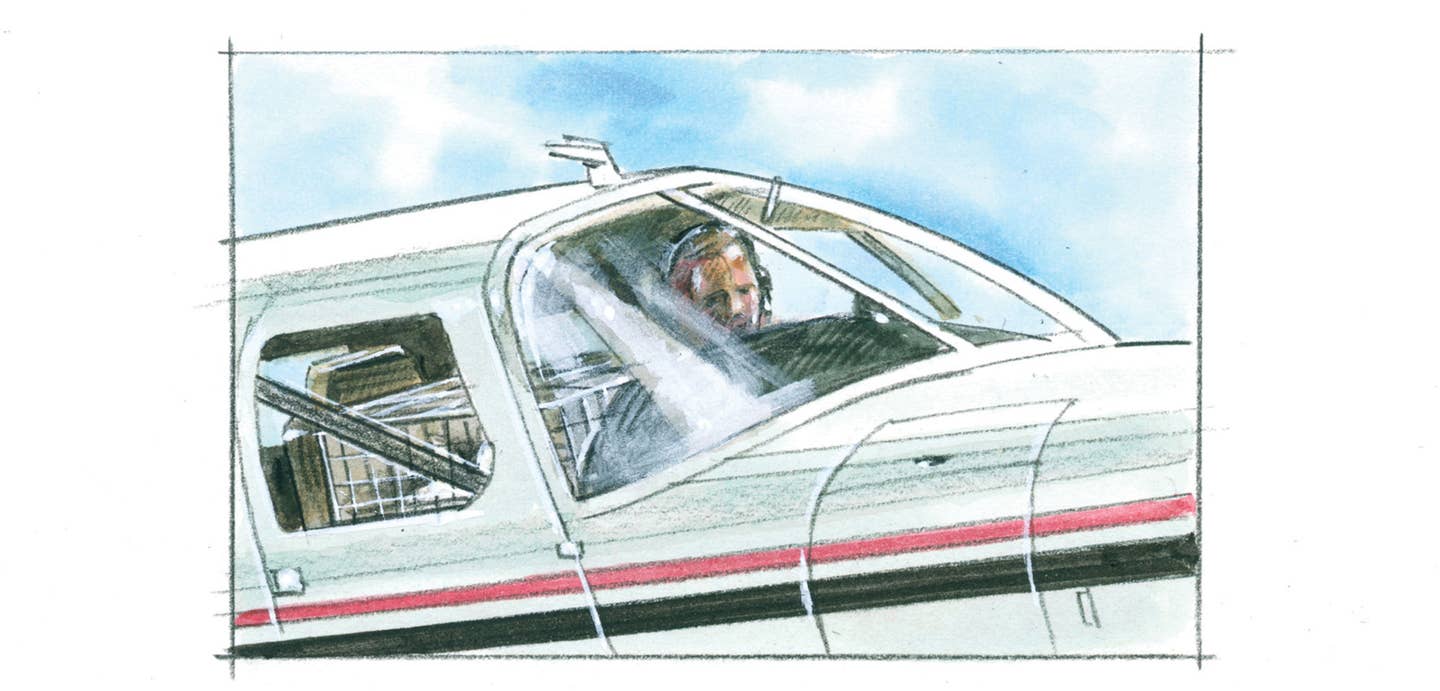

Ferrying lab rabbits to Denver in a Piper Lance got a little hairy in the ’60s.

Illustration by Barry Ross

Being a pilot has been a life goal since childhood, but my primary career for 42 enjoyable years was as a U.S. and international secondary-level teacher, primarily of French.

While a junior and senior at the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley, I worked part-time washing dishes in The Little Chef café, just a block from where I lived across the street from the campus.

A woman who worked in the university job placement center often came to the café for lunch and, over a period of time, we became good acquaintances. Near the end of my senior year, she said, “Jim, when you get ready to graduate, come to my office and we’ll talk about your plans.”

What plans? I didn’t have any. Being a teacher ranked far behind a pilot, but she told me, “I know the principal of Lesher Junior High [School] in Fort Collins. If you like, I’ll arrange an interview for you.”

The “interview” was hardly worthy of the name. The principal, his assistant, and I just had a friendly, get-acquainted chat for a short while. I kept wondering when the job interview would begin when the principal said of the woman from the placement office, “Well, anybody she recommends, I’ll hire.” And so I had my first job. The others during my long career were mostly just as easy to obtain, pretty much “on a silver platter.”

Besides teaching in Fort Collins, a favorite pastime was flying as much as possible from the local airport, Valley Air Park (VAP), just at the edge of town. A friend and fellow teacher in the same district, Dana Jeffries, and I owned a Cessna 150, a bit unusual because it was equipped for IFR flight, so that advantage was used to begin training for an instrument rating.

After a couple of years, we upgraded to a four-seat 1967 Piper Cherokee 180, N975J (November niner-seven-five-Juliet) in which I obtained a commercial certificate, which basically meant one could fly for profit instead of being required to share expenses with passengers.

The Cherokee was a wonderful airplane in which we traveled over much of the United States. A few major trips from Fort Collins were to Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico, San Diego, Seattle (plus a bit of Canada), Glacier and Yellowstone national parks, and even to the Florida Keys. After eight memorable years and almost totally maintenance-free flying, we sold that airplane for the same price we paid, a reasonable investment for a fantastic way to see our country.

Because Valley Air Park was my home airport, among my acquaintances, there was the airport manager, Elliot Ray, a couple of instructors, and other local pilots. VAP-based pilots had recently begun making flights of about 30 minutes to Denver and the old Stapleton airport, the forerunner of the Denver International Airport (KDIA). Usually, there were also passengers waiting for a return trip to Fort Collins.

…After letting them ooh and aah a bit, I confessed that, in my case, TWA stood for ‘Teeny Weeny Airline.’… But I was flying…and happy as could be.

One day, a totally unexpected phone call came from Ray wanting to know if I would be interested in flying some of the Denver trips on a part-time basis because he knew of my teaching job and commercial certificate. His offer was like asking a kid if he would like to work in a candy store for pay and free candy. It pleased me to be offered a pilot’s job I had not applied for, and the offer was accepted without even asking how much it paid.

Ray gave me a checkout in a six-seat Piper Lance, one of my favorite planes, and all of a sudden I was an official airline pilot, albeit for a very small airline. In fact, when people would ask which airline I flew for, my straight-faced answer was, “I fly for TWA” in reference to Trans World Airlines, a very large and prestigious carrier of the 1950s and ’60s. After letting them ooh and aah a bit, I confessed that, in my case, TWA stood for “Teeny Weeny Airline,” but I was flying one, two, or even three trips a day either after school or in the evenings and weekends and happy as could be. About 75 hours were logged in the Lance alone.

Only 50 round trips later, and just as they were preparing to add a couple of twin-engine planes to the Denver runs, all operations at VAP closed permanently. Of those flights, 49 were very routine, but one trip still remains quite vivid in my mind, even to this day.

The airplane for that particular trip was the Lance, and all five passenger seats were occupied. We had a standard safety rule just before takeoff of switching to the fullest fuel tank, so I reached down to the selector lever, more by feel than sight, and moved it one notch to the right to put it on the right main tank. Takeoff was normal, and soon we were climbing southbound above Interstate 25.

Because these were short flights, we did not fly high but cruised at only about a thousand feet above ground level—and all was going well. Suddenly, there was a very loud silence as the engine just stopped running. It didn’t run rough or lose power gradually as an engine might do in case of something like ice forming in the carburetor. It just quit running.

None of the passengers said a word, not even anything like “What happened?” or “Are we going to crash?” or “I’ll report you to the manager if we get to Denver!” The cabin was just as quiet as the engine.

This trip quickly turned into one of those Ripley’s Believe It or Not stories. Of all the trips I had made to Denver and back to Fort Collins, this was the first and only time there were no human passengers aboard. In fact, of the 1,800-plus hours recorded in my logbooks, it is the only one on which my passengers were not people. The five seats were occupied by five wire cages, each holding one or two rather large white rabbits being transported to Denver for medical research, and since I didn’t think any of them would report me, I decided not to mention the incident either, not in Denver and not at VAP. And I never did. I had learned a valuable lesson in a short time about double-checking when switching fuel tanks on the ground or in the air.

The Cherokee that Jeffries and I flew so often had only two fuel tanks, one on each side in the wing near the fuselage, so switching tanks was a no-brainer. But the Lance had four tanks, one main one in the wing on each side near the fuselage, but there were also two smaller ones, called tip tanks, with one on each side near the outer tip of the wing. These usually were filled only for longer trips but not for these short Denver flights.

The fuel selector switch on the Cherokee, an arrow-shaped knob, could be turned to point to either the left or right tank, and it was located on the pilot’s side wall below the window near the floor and easy to see and operate.

On the Lance, the selector was a lever that protruded from below the center of the instrument panel and could be moved right or left to indicate which of the four tanks was to be used. The indicator was down low below the instrument panel and was quite small. Hopefully, that was improved on later models. So I switched tanks more by feel than sight, and what really happened was I moved the indicator from the right main tank to the right tip tank, which apparently had just enough fuel to get us airborne and a couple of miles en route but high enough that the problem was easily solved.

The solution was quick and simple. The prop was still windmilling, so all I needed to do was switch on the electric fuel pump then select a main tank with fuel in it. In a matter of a few seconds the engine roared back to life— a very welcome sound.

Being a Christian, I like to thank the Lord and his angels for any help they provide in such situations because I feel he had the solution ready before I even faced the problem. It might even suggest that the Lord has a sense of humor. Events like that have happened several times in my aviation experiences and could provide “fuel” for future articles.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox