New Pilot Ratings Mean New Radio Challenges

It ain’t easy doing words good. Read about the complications this pilot faced while trying to earn new ratings.

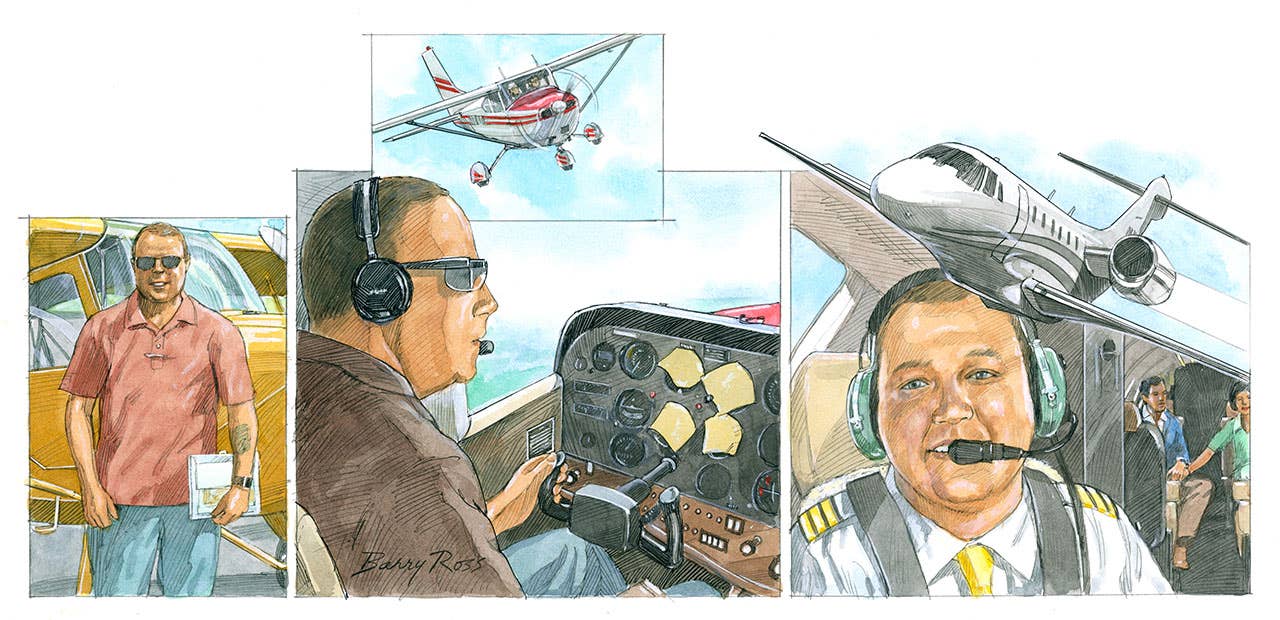

Art by Barry Ross

Ask any pilot what they struggled with most in their training, and I bet the majority will say, "The radio."

My first 22 years in aviation were spent as a maintenance technician of one sort or another. I've been an avionics tech, A&P, IA and director of maintenance (D.O.M.). I've spent a lot of time taxiing jets around various-sized airports, mostly GSO and CLT, so I felt pretty confident about my radio skills. Until I started flying.

I showed up for my first flying lesson in the mighty Aeronca Champ early in February 2017. When my instructor and I talked about communications, I proudly declared that I was already familiar with using a radio, and I felt pretty good about it. My instructor hand-propped the airplane, got in the back seat, and ran through the typical pre-taxi procedure. He said, "Go ahead and let CTAF know we're taxiing to run-up for two-three."

"Let who know?"

"CTAF. The common frequency."

I wrote "common frequency" on my shiny new kneeboard and said, "We're going where?"

"The run-up area for runway two-three."

I wrote "run-up 23" beside "common frequency" on my kneeboard, looked confidently down at the instrument panel, up out of the windshield, then expertly said, "I don't know how to do any of that."

Over the next several months, I learned what to say on frequency, when to say it, and, most importantly, when to shut up and listen. When I took the check ride for my private pilot certificate, I was, again, pretty confident with my abilities on the radio. Until I started instrument training.

I studied for my instrument rating. A LOT. I listened to LiveATC. A LOT. I listened mostly to Daytona Beach tower and approach because that's where Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University is based, and there are always plenty of students stammering on the radio, just like I was. It was an invaluable resource, and I learned a lot.

My instrument instructor used a great method of teaching radio independence. He was responsible for 100% of the radio communications at the beginning of my IFR journey. Gradually, and mostly undetected, I was handed more and more communication duties. He handed me the mic to request a practice approach here and an on-the-go report there. When it was time for my instrument check ride, I was handling the flying AND the talking.

As an aside, the two favorite quotes from my instructor, Ron, during instrument training are:

When I didn't understand the approach clearance a controller issued to us: "You talk fine on the radio; you just need to listen faster."

And:

A slight tap on my shoulder: "It's a push-to-talk button, not a push-to-think button."

Once I made it through my instrument training, I felt confident in my radio communications. Until I started my commercial training.

Well, that's not completely accurate. The commercial rating is often seen as a time-building rating, after which you're expected to understand laws, regulations and generally be capable of getting yourself around every chunk of airspace that the United States has to offer. This rating puts the "pro" in commercial. Or something like that.

My friend Joe and I started working as avionics technicians together back in 2001 at the GSO Citation Service Center and have remained close friends ever since. We began our flight training within a few days of each other, and we have a spirited attitude of competition between us.

As Joe and I were building time for our commercial ratings, we challenged ourselves by flying into congested airspace on some days and playing ATC on approaches while the other was under the hood on others. When we flew together, it was fair game at any time to call out engine failures, fires, commando attacks, etc. Neither of us cut the other any slack, and we had an absolute blast doing it.

I passed my commercial check ride, then, shortly after, I passed my commercial-multi check ride.

I felt confident in my radio communications in single- and multi-engine airplanes at that point. Until my first leg in the right seat of a jet.

ATC talks differently to people in jets. When they talk to a piston single, most of the time they'll mirror the speed of the pilot's speech. I don't know if it's intentional, but it happens. The default cadence of ATC talking to a piston single is that of a concerned citizen helping the airplane cross a busy street. The default cadence of ATC talking to a jet is that of Niagara Falls helping you into the water.

The patient gentleman, Matt, with whom I was flying my first day in a jet, walked me through how to get us out of a non-towered airport and on the way home with our passengers.

"Here's the frequency for clearance delivery. If you can't get them on the frequency, give them a call at this phone number. Tell them we want a hold-for-release clearance. They'll give you the clearance just like they do at home, then we'll call them when we're ready to go."

On the leg home, I was caught off guard completely when the center controller gave me three (the maximum) instructions while we were still almost 200 nm from home. It went something like this:

"Citation 7EC, contact Atlanta Center, 132.35."

I read back the instruction and went over to Atlanta. I wasn't expecting anything more than a regular check-in.

"Atlanta, Citation 7EC, FL370."

"Citation 7EC, descend and maintain FL240, published speeds at FLLGG, descend via the STOCR3 arrival landing south."

I got as far as pressing the "direct" button on the FMS before forgetting every English word I'd ever learned. It must've been the blank stare on my dumb face that clued the PIC in to the fact that I was stuck in an endless loop of stuckness. He keyed up the mic and read back, "Descend and maintain FL240, published speeds at FLLGG, descend via the STOCR THREE landing south, 7EC."

I'm not saying my instrument instructor didn't prepare me for STARs (standard terminal arrival routes) because he did. The problem is that piston airplanes typically don't fly arrivals, and it's very difficult to teach someone how to fly an arrival without being able to demonstrate it properly.

STARs for piston airplanes are usually not more than a heading and a fix, which works just fine, but the complexity of arrivals applicable to jets is something that is fairly difficult, if not impossible, to teach at 0' AGL and 1g.

I apologized to the PIC for words not coming out of my face, and he graciously let me off the hook before showing me how to set the arrival up in the FMS. We landed uneventfully, and my first 1.8 hours of turbine time was complete. To quote Gary, my aviation hype-man, "I was so far behind the airplane that, after we took off, I looked back and saw myself walking out of the FBO."

"My friend Joe and I started working as avionics technicians together back in 2001 at the GSO Citation Service Center and have remained close friends ever since. We began our flight training within a few days of each other, and we have a spirited attitude of competition between us."

I'm a tactile learner, so, much like learning how STARs work, I can't grasp a concept until I've been neck-deep in it. If I learn a lesson the hard way and it hurts, it tends to stick. The more it hurts, the better it sticks.

After that first flight, I studied the STAR charts quite a bit more WHILE I was listening to LiveATC. Hearing the same thing over and over again said the same way is also very helpful to me.

I've flown about 250 hours in jets now, plus another 70 hours in level-D simulators, and I think I'm just starting to get to the point where I'm learning how to communicate on a professional level. I still get the occasional instruction with which I'm not familiar where my more experienced mentor has to help me a bit, but those cries for help are becoming fewer and further between.

As I asked for advice from experienced pilots and controllers on how to do words good, the vast majority have said some version of, "If you ever get confused, flustered or overwhelmed by ATC, fess up. Quickly. The absolute worst-case scenario is that you'll hear an irritation in the controller's voice as they begrudgingly give you simpler instructions at a slower pace. Far more often, you'll hear empathy in the controller's voice as they happily give you simpler instructions at a slower pace."

"I'm a tactile learner, so, much like learning how STARs work, I can't grasp a concept until I've been neck-deep in it. If I learn a lesson the hard way and it hurts, it tends to stick. The more it hurts, the better it sticks."

We can't always sound like Chuck Yeager on the radio, and we have to keep in mind that controllers didn't start off sounding like Houston mission controllers, either. Sometimes it's tough to remember that the sound coming out of the headset is just a person doing their best to keep airplanes from fusing together.

As an experiment, one of these days, I'm going to check in with, "Center, good afternoon, Falcon 7EC, student pilot, FL410," just to see if I get a reaction. Better yet, "Center, good afternoon, Falcon 7EC, maintenance, FL410." That should get a rise. Or at least a pause.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox