Memories Of A Former Spitfire Pilot

A pilot honors his mentor, sharing several of the stories he heard.

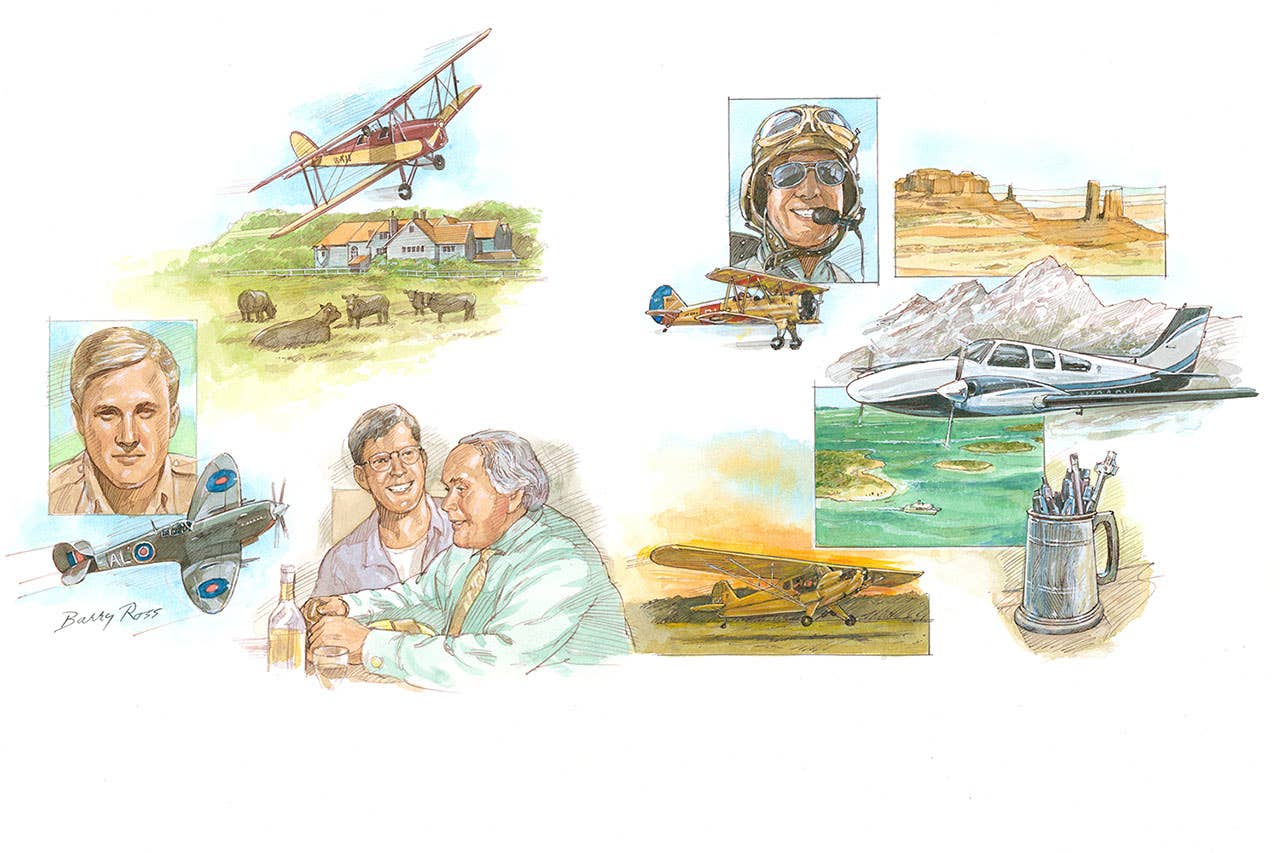

Illustrations by Barry Ross

It was 20 years ago,or more, and I was studying for my master's degree at the London School of Economics. Flight Officer Michael "Dicky" Reid (we called him Mick) was the father of a good friend of mine at the LSE. His white hair was unkempt, and he was blind in his latter years. In his prime, he was a pilot. He flew the Spitfire in combat over Europe in the waning days of World War II. In the immediate postwar years, he flew evacuation top cover in various places as the British Empire retreated, like the tide, from the far reaches of the world toward home.

He lived at Maplesden, a sprawling and ancient farm home an hour's train ride south of London. He and his wife, Nima, were kind enough to host several of us students in need of a quiet place to read and write up our dissertations. Which we did, over the course of that summer, in between row-boating on the family pond, eyeing trout in the brook and walking the family spaniel on the hills. The initial excavation work on the swimming pool at Maplesden was accomplished by an errant buzz bomb in the waning days of World War II.

The afternoons were quiet and cool. Along with the gentle breezes and the buzzing of insects in the garden, I could hear him talking on the telephone and the occasional chatter from the radio in his office. The hourly news report, cattle prices and the weather. He marked time by a talking clock on his desk. Click. "The time is now!"

Nearing sundown, when the clock told him it was five, or six, or whatever hour pleased him, you could hear the scratch of the chair on the stone floor.

"Charlie Kilo!" he would bellow. The phonetic letters of my name calling from down the halls and around the corners. Books shut, pencils went down, and thus would begin the evening. Sitting at the end of the wooden table in the kitchen, he would talk, and I would listen.

I learned the route from Beachy Head to Biggin Hill when the weather was so bad you were forced down to 100 feet or less, the cold rain congealing in droplets along the cockpit coaming. Sitting in his chair, the long-vanished spade grip in his right hand and the throttle in his left, he flung his eager craft along the country lanes, railroad lines and hedgerows, settling over the mist-shrouded trees and onto the turf of home, the Merlin rattling and popping as his nimble little fighting machine paid off in the flare.

I was not yet a pilot in my own right, but I was steeped in the lore. My father was a crop duster, and I was reared on a grass airstrip in Florida to the music of Pratt and Whitney radials. My questions must surely have been tiresome, but they did prompt a flood of tales from him and even more fond memories of my own. Both of us sitting there in the kitchen, smelling the supper on the stove, remembering the blessings of life lived with airplanes.

That wasn't all. We tried, on successive nights, to see if we could collectively piece together the entirety of Thomas Gray's "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard."

"There's something of a ’hoary-headed swain' in there, Charlie Kilo. Don't you recall it?" he would ask.

"’Oft have we seen him!?'" I would hesitantly reply.

"Ah, yes. That's it. ’Oft have we seen him at the peep of dawn/Brushing with hasty steps the dews away/To meet the sun upon the upland lawn.'"

So it would go. Long years had passed since I had learned these lines in Ms. Unold's British literature class, and years further still since his own schoolboy days. Between us, we got pretty close to completing the whole thing without having to look it up in Nima's library down the hall.

We talked of the labors of building and maintaining a prize herd of Sussex cattle, which he had done. He was curious about the raising of peanuts in the sandy soil of far-off Florida and my own experience as a farm boy raising pigs. He shared with me the joy of flying his little Tiger Moth off Maplesden in the decades after the war, of running it over to the Isle of Wight for agricultural society meetings. That was before he lost his sight and had to sell it.

My life in Washington prior to my moving to London prompted him to recount the tale of dropping leaflets of protest over central London when some British government or the other saw fit to fete a leader who hailed from behind the Iron Curtain. Just when I thought this yarn seemed a little far-fetched, he reached in a desk drawer and produced a contemporary newspaper clipping that confirmed the whole thing.

The companionable summer evenings gave way to the more ordinary cadence of life. The readings were finished. The dissertation was written and handed in. My life moved away from Maplesden and England and back toward home and work.

As I was returning to ordinary life, he was drifting away. He passed just after the turn of the millennium. He was buried in a wooden casket, decorated by his Nima, and with a bottle of whisky by his head. His placeholder stone contained a line from John Gillespie Magee Jr.'s "High Flight."

"Oh, I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

"And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings."

That was another poem we would work on together during those evenings in the kitchen. It was easier, that one, than Gray's "Elegy."

The thread of my life since reconnected me to the blessings of aviation. In my own hours in the cockpit, I have experienced firsthand the happy interplay of the technical and the sublime. I have run low, like a rabbit, over the farming fields of Illinois and Missouri in an open cockpit biplane. I've looked out the windshield of our Baron at the Tetons and Monument Valley. I've seen the islands of the Bahamas placed like jewels on a sea of heart-stopping blue. I've followed my own familiar country lanes and fence rows toward home on quiet summer evenings, moving from the ethereal to the temporal as the Cub settles in the waning twilight.

On occasion, I remember that kitchen and the happy hours we spent there. Hours that won't make it into any logbook except the one in my own mind. The tangible evidence of those moments has dropped, for the most part, over the far horizon. The cattle herd was distributed. Maplesden was sold. I do have a pewter mug Mick gave me, and it holds the extra pens on my desk as I write this. It was presented to him by his friends in agriculture on the occasion of his marriage.

"I was not yet a pilot in my own right, but I was steeped in the lore. My father was a crop duster, and I was reared on a grass airstrip in Florida to the music of Pratt and Whitney radials. My questions must surely have been tiresome, but they did prompt a flood of tales from him and even more fond memories of my own."

A couple of summers ago, I returned to England with my family. Mick's son Dickon was kind enough to take me to the old Stonegate churchyard to visit his grave. As I stood there on a lovely summer afternoon and listened to the wind through the trees, I had an irrational wish to hear that talking clock: "The time is now!"

Instead, I was left alone to surface a fond memory or two and contemplate anew the lines from Shakespeare engraved upon his headstone:

"His life was gentle and the elements so mixed within him that nature might stand up and say to all the world, This was a man."

Do you want to read more Lessons Learned columns? Check out "Common-Sense Solutions For Winter Flying!"

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox