Lessons Learned: High Desert Flying In A Cessna 150

When flying in hot and high conditions, extra engine power is your friend. But what if your plane doesn’t have any?

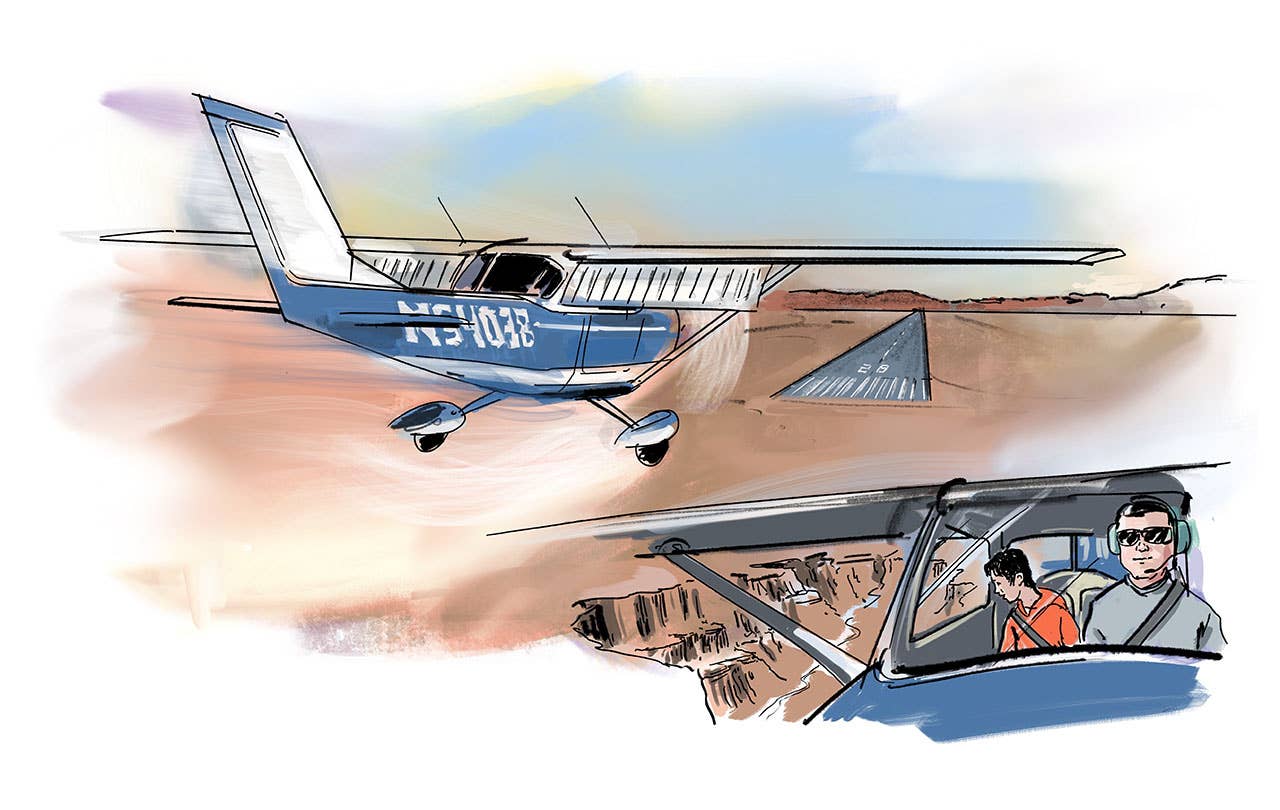

High Desert Flying. Illustration by Gabriel Campanario

My 7-year-old son's last day of school rolled around, coinciding with the week of Memorial Day. I decided to take that week off of work to go on an aerial adventure. I thought it would be a great idea to fly down to Arizona and check out the Grand Canyon from the air.

I was a little apprehensive, though, as I was a flatlander flying out of our local airport in Indiana. The furthest away I had flown from our home airport, Monroe County in Bloomington, Indiana (KBMG), was Alabama, or was it Iowa? (And there were several fun jaunts to the islands in Lake Erie in Ohio.) None of those destinations were terribly challenging, although the short runway at Put-in-Bay, with tall trees on either end, had a bit of a pucker factor to it. Still, the worst density altitude I had experienced was my home airport on a hot summer day, and I was still able to climb above 10k feet that day.

With only around 300 total hours and no IFR rating, I knew I was in the statistical danger zone and didn't want to take any additional chances. I knew the high DA's of the high desert were not to be taken lightly, but I didn't really know what it felt like to take off in those conditions. My steed for the trip was my blue and white 1968 Cessna 150H I affectionately named the Dirty Bird, because I never washed it. Hey, oil on the belly helps with corrosion, amirite?

Even though it had a climb prop, I still never got more than 500 feet/minute, although to prepare, I did make a couple of high-altitude flight tests, at one point topping out at 12k feet with a bit left in the engine. I felt that mechanically she was ready, but was I? I ordered a mountain flying book online a few weeks before the trip, but with less than a week to go, it still hadn't arrived, and after inquiring with the seller, he confirmed he made a mistake, didn't ship it, and, in fact, didn't even have it in stock.

By then, it was too late, so I did a little bit of internet research before the time came to leave and hoped for the best. I like to think of myself as a conservative pilot by nature, so I figured that as long as I took things slow, which is default for a 150 that tops out at the speed of smell, and didn't take any chances, things would be fine.

And they were. We departed KBMG early in the evening with a planned stop in Creve Coeur, next to St. Louis, for the night. With the exception of flying around a few storm cells, the flight was uneventful, and the next morning we took off amongst the scattered, low-level clouds over the green grass of Missouri. We stopped for gas and a snack in Fort Scott, Kansas, and while the terrain was rising, I wasn't noticing any major effect on the plane yet. Things were about to change.

"My steed for the trip was my blue and white 1968 Cessna 150H I affectionately named the Dirty Bird, because I never washed it. Hey, oil on the belly helps with corrosion, amirite?"

We continued on, stopping for gas and fast food burgers in Alva, Oklahoma. It was a blisteringly hot day, in the upper 90s by the time we landed, and I was glad that the ancient Buick the FBO had for a courtesy car had working air conditioning. We weren't so fortunate in my plane, though, as we were dripping sweat before we even got to the runup point. Here was my first taste of high-density altitudes. We used up half of the 5,000-foot runway before we lifted off, and my climb trajectory was decidedly flat at a leisurely 300-odd feet per minute. We soon left behind the crop circles of the plains, green pancakes as far as the eye could see, and traded them for the desert as we landed at our final destination for that night, Dalhart, Texas.

Even though the morning air was much cooler than the afternoon heat of Oklahoma, Dalhart is at nearly 4,000 feet MSL, and so again my little bird struggled off the ground. One thing I noticed during my flight planning, though, was that the runways seemed to get longer and longer the further west we went. One of my buddies flies a Socata out of a 2,000-foot grass runway a few miles west of where I live and doesn't have any issues. Because his wife has family in New Mexico, he makes the trip frequently and warned me about the mountain pass between Albuquerque and Santa Fe. Guess where my son and I were heading next?

Even with high-density altitudes looming, after the monotony of the flatlands, the mountains were a welcome sight, and it was the first time my son had seen them. It's hard to get a sense of scale from the air, though, and since he's been flying with me since he was 4 years old, GA flying is not as novel for him as it is for most other people. We were on our way to Double Eagle on the west side of Albuquerque, and shortly before we got there flew around the north side of the Sandia Mountains. The views were spectacular, and, luckily, we didn't encounter the chop my friend had warned us about. He said his wife put a dent in the roof of their plane during one particularly bad round of turbulence.

Our final destination was Flagstaff, Arizona, but before that, I wanted to fly over the Grand Canyon. There are several VFR corridors one can fly down, and with my performance- limited plane, I didn't think I could make the 11,500 feet for the northbound leg, so I decided to swing north and hit the Zuni corridor south at 10,500.

Leaving Double Eagle, however, we encountered a pretty vicious headwind, and our GPS only indicated 70 knots of ground speed. Even though our fuel burn was lower than usual due to the thin air, I didn't think I would have the range to make it all the way to both the Grand Canyon and Flagstaff, so I made the decision to play it safe and stopped in Gallup, New Mexico, for gas.

While the landing was uneventful, despite the gusting crosswind, I was nervous about taking off again. I topped off the tanks to make sure that we had plenty of gas, and with our baggage and my tiny passenger, we were still 100 pounds under gross. Checking the weather report, though, I did see that the density altitude on the ground at Gallup was 9,100 feet. My performance seemed okay going in, so I decided to give taking off a try. Gallup, fortunately, has a 7,300-foot runway, and I used the 50/70 rule, which says that if you haven't reached 70% of your takeoff speed by the time you've gone halfway down the runway, abort the takeoff. My wheels actually left the ground at the halfway mark, and the first few hundred feet of altitude came easy. That's when the trouble started.

I got about 500ft AGL, and my plane stopped climbing. I was at best rate of climb (Vy) speed and wasn't getting any more altitude. I switched to best angle (Vx) and still nothing. The problem was the ridgeline west of Gallup that was getting closer to us. I started zig-zagging, pleading my old, wheezing bird for just a little bit more.

After 20 minutes of futility, I decided to head south a bit and fly over I-40 as a contingency, but just as I started the turn, we got a friendly thermal that rocketed us up a few hundred feet. Then another, then another, and before I knew it, I was at 11k feet, watching the majestic views of the Grand Canyon, spanning from horizon to horizon, opening up before us. It was spectacular.

"If I had maintained my rate of descent, I would have ended up in the side of the mesa short of the runway, and that would have ruined my day."

This wasn't the end of our adventures, though. After a couple of days seeing Arizona from the ground, we headed back home. I decided to make a little detour to check out the Bradbury Science Museum in Los Alamos. Los Alamos is a funky airport in that, no matter what the winds are doing, every approach lands on 27, and every departure leaves on 9. This is to avoid flying over the restricted airspace of the research facility. So we did.

After a nearly four-hour flight with helpful tailwinds, I swung north over Santa Fe and set up my westward approach, with a northerly quartering tailwind. With the tailwind, I was worried about stopping in time, so I came in with 30 degrees of flaps on final.

It was then that things got hairy.

Those wonderful thermals are helpful when you need altitude, but I soon learned that they work the other way around, too. On short final to Runway 27, there's a clutch of white-roofed buildings, and as soon as I got over them, the thermals stopped, and I dropped like a rock. If I had maintained my rate of descent, I would have ended up in the side of the mesa short of the runway, and that would have ruined my day.

I dumped that second notch of flaps to cut drag and firewalled the engine as I paid careful attention to my attitude to avoid stalling. By doing so, I arrested my descent enough to stabilize my approach, bringing the Dirty Bird in for a decent crosswind landing.

Don't be afraid of high-altitude flying, even in a Cessna 150, but take your time, be respectful and don't take things for granted. And always remember, thermals giveth, and thermals taketh away.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox