My Cross Country Flight With A Queasy Co-Pilot

There was no getting around the bumps.

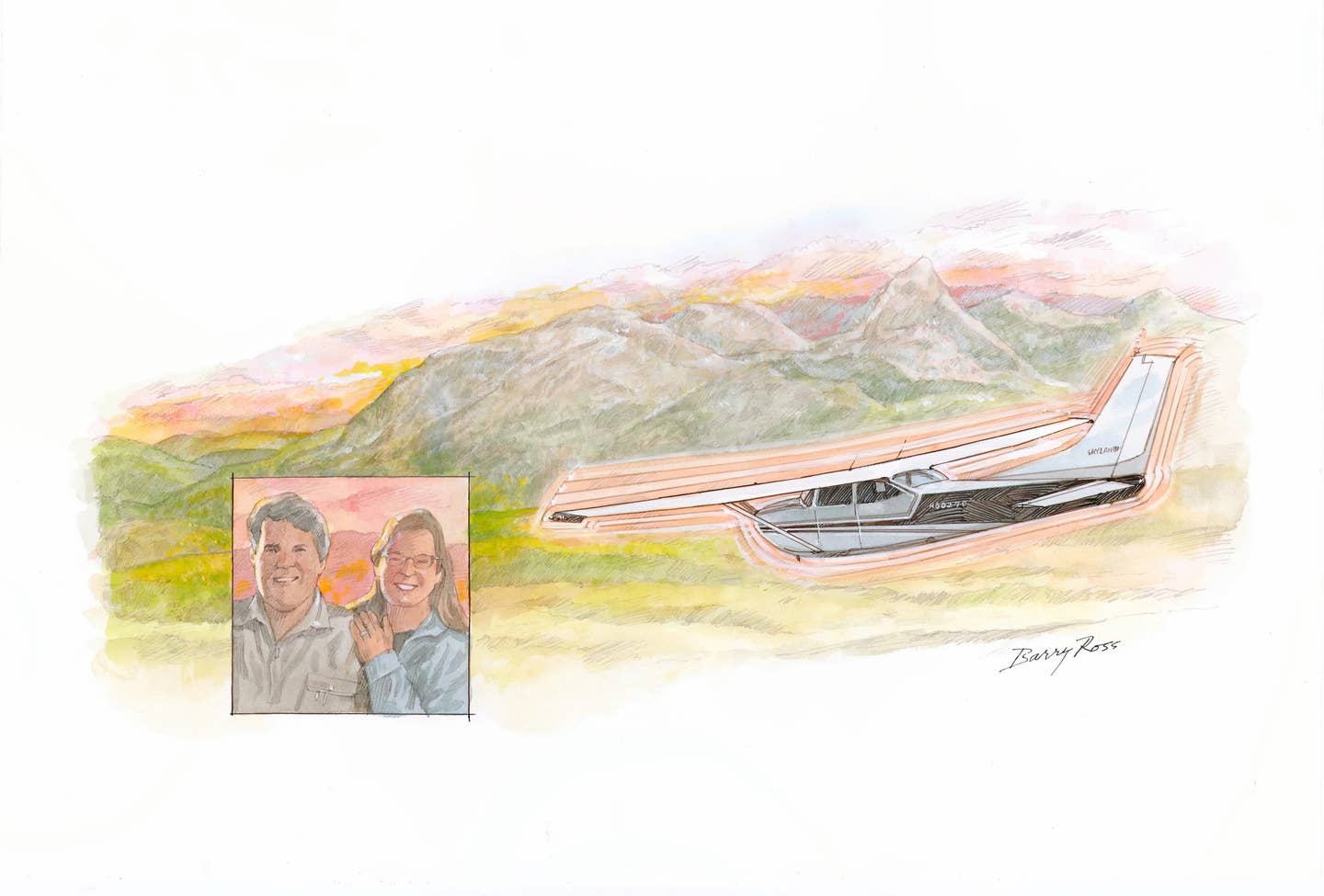

A pilot flies his motion sickness-prone wife to a destination wedding. Illustration by Barry Ross

Question: How do you convince a wife who is prone to motion sickness to join you on a cross-country flight in a single-engine airplane in the middle of the summer? Answer: You tell her you will fly her to her nephew's wedding and assure her that you will try to avoid turbulent air conditions and stop en route at any time.

The June wedding was set to take place at the Brasada Ranch in Bend, Oregon. We had talked about flying commercial, but with the ability to take time off from work and leave at our convenience, it seemed more cost effective and efficient to just fly ourselves. I was excited to fly this trip as it was going to be a long-awaited vacation and my first trip to Oregon from Minnesota in a Cessna 182RG aircraft.

The flight plan was set for us to depart from Crystal, Minnesota (KMIC), early in the morning to take advantage of the cool temperatures. Our first stop would be Sioux Falls, South Dakota. We would then continue west toward Billings, Bozeman, follow the I-90 corridor to Missoula over Lookout Pass, then overnight in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. The next day, we would depart and fly southwest directly into Redmond, Oregon.

We set off in the morning, slightly later than I had initially planned. In my defense, I still had a bit of packing and flight planning to do, but because of the late departure, the afternoon temperatures had started to climb quickly and produce conductive activity over the farmlands in the Midwest. In spite of modifying the cruising altitude for smoother air, my best-laid plans went awry. After much protestations, my wife and co-pilot insisted we land in order to allow her to lie down, vomit and faint. Because of the departure delay, prolonged and consistent convective battles with thermals resulted in a very bumpy ride. The trip was not starting out as smoothly as I'd hoped.

The first fuel stop was at Hot Springs Municipal Airport, South Dakota (KHSR). After landing, I decided to modify the flight plan to take a southerly route to just north of Casper, Wyoming, where we could head west toward the Tetons. The forecast wasn't promising. The convective conditions were expected to persist through southern Montana for more than the expected flight time. After a small respite in an air-conditioned pilot lounge, I offered to stop the flight and proposed the alternative route. My noble co-pilot (her idea) agreed to proceed further just to get out of the Midwest and reach the cooler weather over the Tetons. Unless we were away from the heat, the convection activity along our original route would likely be around the next day.

With the new flight plan approved, we took off to the south, flying to Casper/Natrona County International Airport (KCPR). This southerly route would prove to be cooler and just as beautiful. The plan would have us flying around the southern end of the Tetons at a lower altitude but in cooler, hopefully less bumpy air.

Approximately 100 nm from the rising terrain just east of the Tetons, Minnesota FAA Center contacted me to amend my IFR plan and suggested a route change to avoid traffic. We were instructed to fly directly west to Pocatello, Idaho (KPIH), above the 13,000--14,000-foot terrain of the Tetons, provided we had the required oxygen for high-altitude flying. I confirmed the onboard oxygen and accepted the proposed IFR flight plan changes. For the next 100 nm, I carefully monitored the Tetons, looking for clouds above the mountains since the outside air temperatures flying at 16,500 feet would be subfreezing.

Before long, my co-pilot, ever the canary in the coal mine, announced that she was feeling ice crystals blowing on her face through the air vents (her trick to abate motion sickness) and was concerned for icing. I heard her concern, but my focus was not on the apparent fogging and frozen moisture build-up on the aircraft windscreen, as I was specifically monitoring the struts and leading edges on the wings for any signs of ice formation. Having lived in Minnesota for many years, I've had significant experience with icing conditions on many long cross-country flights in the past. I was used to watching for icing conditions and noticed that these conditions were light and not sufficient to cause any aircraft control issues unless we continued for a significant flight time in the clouds.

After several minutes of flying, the ice did begin to start to form on the leading edges of the plane, and so I executed a rapid U-turn. As we had flown closer to the Tetons, I was able to discern that we would be flying through clouds at the altitude required for proper terrain clearance. After changing our course, I waited until 5 to 10 nm from the rising terrain, then contacted ATC to modify the flight plan back to my originally filed IFR plan.

After approval, we proceeded, turned south to fly the eastern side of the Tetons, then headed west to Pocatello, Idaho (KPIH), for an overnight refueling stop. After a total of five flight hours from starting, we made it into Pocatello for the evening. My co-pilot was pleased to be on solid ground again and to be able to stretch out. She soon began to relive her "near-death" first-time icing experience. I knew once we had eaten, rested and enjoyed the lovely sights of Pocatello, all would be forgotten as it was a relatively uneventful trip. As I had expected, her lack of understanding of the icing conditions and a technical explanation proved sufficient to calm her nerves.

The remaining flight leg the next day to Redmond, Oregon (RDM), was uneventful, without any high-elevation terrain, convective weather or flight plan changes. We were rested and energized and able to finish after a total of 10 flight hours.

As part of my flight planning routine, I have come to expect that I need to have alternative plans for possible inclement weather for a susceptible motion-sick passenger. For many people, motion sickness is a sensation of dizziness, lightheadedness or nausea when traveling by car, boat or train. About one in every three people are considered highly susceptible to motion sickness. Everyone can get motion sickness, but some groups of people are more susceptible than others. The reason for this difference is not well understood. As a result, I have learned to request rerouting when ATC directions are not conducive to safe or comfortable flying conditions for my passengers or when my co-pilot instructs me otherwise!

Flying allows me the opportunity to challenge myself and experience a variety of situations from long cross-country trips, mountain flying, turbulent or convective avoidance, and inclement weather rerouting. Passenger comfort and enjoyment are critical considerations for cockpit safety, to maintain companionship on future flights, and to continue to financially support an expensive hobby.

In the end, the flexibility of planning and flying one's own route, at their own pace, is worth the challenge of navigating around weather along a beautiful cross-country flight. The calculated costs of flying ourselves were comparable to the calculated total expenses of flying commercial. The time savings for convenient and expeditious departures, and the thrill and challenge of flying, more than offset the cost of flying commercial.

The wedding venue at Brasada Ranch in Bend, Oregon, turned out to be lovely. We were not at the mercy of the airlines for tight departure times, safety check-ins or baggage handling. As pilots with our own aircraft, we were treated professionally at Redmond Airport and appreciated the convenient full-service ground transportation, nearby hotel accommodations and reasonable tie-down rates.

Shortly after we settled into a local Redmond hotel, my co-pilot informed me that she would prefer to fly home commercially. Because of her willingness to deal with the bumpy conditions on the flight out, I felt it was a small victory to ensure that she would be open to try another similar adventure in the future. I considered the trip a victorious "win" even if she was only able to fly one way. This flight will always remain a memorable experience for my co-pilot as the flight-from-hell is further recounted as her "near-death" experience, which seems to grow more dramatic with each telling. Luckily, she continued to fly with me and to tease me about who was really in charge of the flight plan.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox