Common-Sense Solutions For Winter Flying

A Maine-based pilot shares the lessons he learned for dealing with the cold-weather insanity.

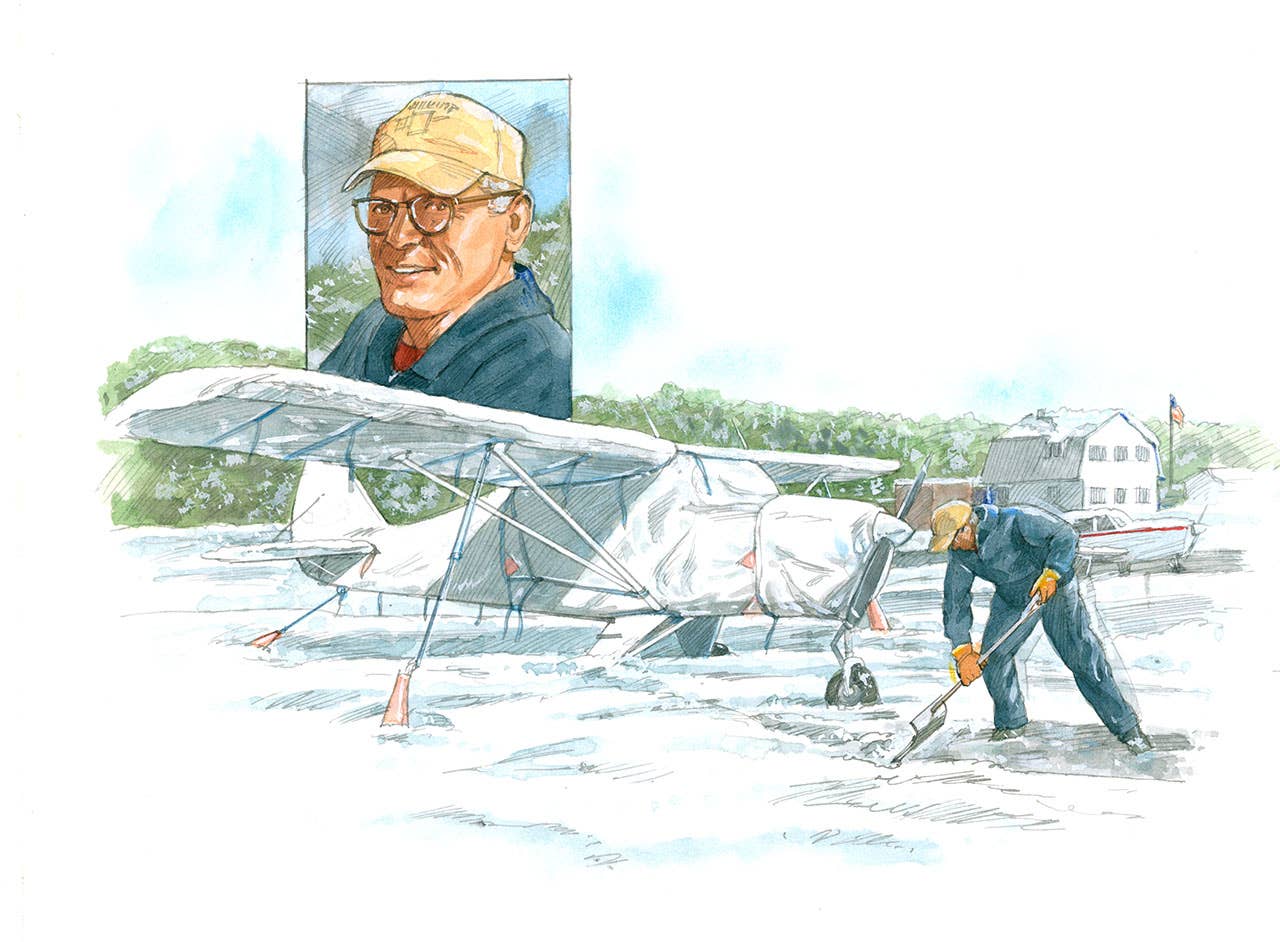

Illustration by Barry Ross

We're not going to talk about "winter flying." Come October or November, every flying magazine in the world runs a special about "winter flying." By now, we all know the ins and outs of winter flying or, at least, we've read everything about winter flying that we care to read.

This is about flying in winter---when you are on a scheduled commute. It's about adding extra time to warm up the plane and clear the ice and snow from in front of the hangar. And it's about all the things that go wrong when you are trying to warm up the plane and clear ice and snow from in front of the hangar.

If you're going to commute year-round by plane and you live anywhere in North America north of the 40th parallel, you're going to have a lot of cold, wintry days of flying. A number of people who live south of the 40th, say folks in the mountains of West Virginia, Tennessee and Colorado, are going to have a lot of cold snowy days, too. But one has to draw a line somewhere.

During my first years of flying from Maine to Massachusetts, I didn't have a hangar, so I didn't have to clear the ice and snow from in front of it. The plane was parked on the ramp at Norridgewock, the Central Maine Regional Airport (KOWK). I hired a local seamstress, an expert furniture upholsterer, to make wing and fuselage covers for my Tri-Pacer.

These covers were a thing of beauty, a complex thing of beauty. It took me a while to figure out how to fit all the straps and tie-backs so it all went on smoothly. The hard part was getting the main fuselage cover up and over the twin antennas on top of the cockpit. Once those antennas found their way through the proper holes, cut especially for them, everything else fell into place. When everything was in place, the plane was completely wrapped up, from wing tip to tail feathers, like an unusually large Christmas present.

Once you've mastered the shortcuts of covering your plane, you then have to learn to do it in a strong wind, at night, sliding around on ice. This is something you never actually "learn" in the cognitive sense. You just do the best you can. More than once on icy, windy nights, I spent more time covering the plane than I did flying home from Massachusetts.

Just because the Rocket was on the ramp did not mean I did not have to clear ice and snow. My winter airport is owned by the town of Norridgewock. The town brain trust evidently takes a legal rather than a common-sense view of snow removal: If plow trucks get too close to the planes, they might damage them, resulting in costs to the town. Therefore, plow trucks stay far away from the planes they are ostensibly plowing snow for. This results in anywhere from 3 feet to 5 yards of snow in front of each plane.

After a mere 6-inch snowstorm, this "front yard" of snow became a pleasant form of moderate exercise, a way to get one's muscles limbered up before flying. After a 30-inch snowstorm, usually followed by blowing wind and drifts reaching almost twice that high, this "exercise" became an hours-long beatdown with visions of the town lawyer freezing to death dancing through my head.

I tried hard to cajole the plow truck driver to get as close to my plane as possible. A man of Norridgewock integrity, he wasn't cajolable.

"Shame on you, are you from New York?" said the look on his face.

"No, I'm from exhausted and fed up with this symbolic snow plowing," said the look on my face. He wouldn't budge.

On the way into the airport, I had noticed his car. It had a large RC airplane model sitting in the back seat. This guy loved airplanes. I asked him if he'd like to go for a short flight.

"I'd love to go for a short flight," he said.

"I've got some time. I'll take you up for a few minutes before I fly to Massachusetts."

"Maybe some other day. By the time you get all that snow dug out in the front of the plane, you probably won't have all that much time. Besides, I've got a lot of plowing to do." And he did. Just not in front of our airplanes.

I tried explaining the obvious: If his plowing did not free any of the airport's airplanes from the deep snow so they could fly, what was the use of all his plowing? It's not as though Central Maine Regional has a lot of guest airplanes dropping by in February. The driver hesitated for a long second. A young man not easily given over to metaphysical inquiry, he finally shrugged and climbed back up and into his giant Air Force surplus plow truck.

I couldn't bring myself to get angry with him. He was a nice fellow, obviously loved airplanes and was doing what the town wanted him to do. Turned out to be a good thing we remained cordial. A few years later, I was at a local medical clinic taking my flight physical. One of the nurses said to me, "You fly a Tri-Pacer, right?" I asked her how she knew that. "My husband plows the snow at Central Maine Regional."

Eventually, I moved the Rocket into an empty open-face hangar owned by my friend Bruce. For $300 for the winter, I had the luxury of foregoing the wing and fuselage covers, and I had an electric outlet right there in the hangar. This made it easy to plug in the oil-pan heater that came installed on the plane's engine. The first owner, way back in 1957, lived in Minnesota and ordered the plane with the oil pan heater plus front- and rear-seat heating. When the plane was sitting out on the ramp, I had to assemble a couple of long extension cords and plug into the airport's terminal building. The town authorities, who were busy making sure the plow driver stayed far away from anything that looked like an airplane or a hangar, didn't seem to notice the spike in their electric bill.

I sold the custom-made wing and fuselage covers to a friend in Massachusetts who had bought a Tri-Pacer. A short time after that, a family of pigeons moved into the rafters of my winter hangar. The general remedy in Maine for unwanted pigeons is to shoot them.

I instead resorted to throwing stones at them. I never hit one. They, on the other hand, managed to hit my wings several times a day. This resulted in the unpleasant chore of removing frozen pigeon presence from the wings before each departure. Bruce is a gun collector and seldom goes about without a firearm. He dropped by one day---while the plane was out---and persuaded the pigeons to find another habitat.

Maine winters can push you pretty hard, but this push comes with a gift: It makes you pay attention to nature, and when you do, you become more aware of the dramatic natural beauty that's all around. This struck me particularly on one cloudless night. I was standing on the ice in front of my rented hangar. The sky was a blanket of stars with the arc of the Milky Way easily visible running in a gray line north to south. All this was made even more dramatic by the complete silence, the heavy blanket of quiet that settles in on a winter night, broken only by the clink and periodic whirr of the airport beacon, twisting slowly on its pole, 65 feet above.

I had just pulled the Rocket out of the hangar by scattering some sand on the ice in front of the nose wheel to give my feet a bit of purchase. I had tried using those slip-on cleats, but when you're tugging on a 2,000-pound airplane, the cleats tend to roll right off your shoes. Sand works better. I had just got the plane moving a bit and was looking up to take in the inspiring display in the heavens. The momentum of the plane was pushing me, gliding me slowly across the ice. That was when my heels hit a ridge in the ice, and I fell backward in front of the nose wheel, one leg on either side of it, with the plane gathering just a bit of speed as it cleared the hangar on a gentle downslope toward the taxiway.

This is not a good position to be in. It seems obvious that the immediate remedy would be to squirm backward faster than the nose wheel is closing in on your personal property. That, of course, is what I tried to do. It became immediately clear, however, that you can't squirm backward as quickly as you would like while your fanny is on glare ice. Out of prudence, I quickly raised one leg and kicked hard at the turning nose wheel, regretting that I had removed the wheel fairings for snowy winter flying.

The danger of kicking a turning nose wheel with the plane bearing down on you while flat on your back is having your foot thrust under the wheel, thereby setting off a series of events that might eventually end with a bystander (attracted by the flashing lights of the First Responders) remarking: "I've seen people run over by cars. I've never seen anyone run over by an airplane, 'specially a parked one with the engine off."

Fortunately, the hard kick propelled me across the dark ice and gave me enough room and time to swim and slide out of the way of both the nose wheel and the main gear. Lesson learned. Now when I move the Rocket around on ice, I bring along more sand, a lot more sand, and apply what the British call "utter caution."

"I tried explaining the obvious: If his plowing did not free any of the airport's airplanes from the deep snow so they could fly, what was the use of all his plowing? It's not as though Central Maine Regional has a lot of guest airplanes dropping by in February."

The first time I plugged the Rocket in to keep the engine warm, I had no idea what to expect. My mind wandered back to the aviation pioneers who landed, quickly drained the oil, and then carried it inside the local terminal shack and put the can somewhere near the woodstove. When they set out to fly again, they carried the can of oil back to the plane, poured the oil in, and started the nicely warmed-up engine.

I'm sure it wasn't as easy as it sounds. If I wanted to drain the oil from my Tri-Pacer, I'd have to lie on my back, do a half-sit-up while I reached up and found the plastic oil drain tube nestled away, untucked the tube, reached further up into the bottom of the engine, still holding that half-sit-up, and released the oil flow valve. Somewhere in there, I would have slipped a slightly larger drain hose over the one connected to the plane and steered that larger, longer hose into a 5-gallon can or plastic bucket. I could let the oil just flow from the plane down to the bucket, but if the wind is blowing---and the wind is always blowing when you need to drain the oil---the oil would flutter all over the place, and only some of it would land in the bucket.

Early fliers who didn't have a nice warm shack nearby sometimes built small fires under their engines to warm them up. There are lots of stories about pilots who misjudged the size of the fire they needed and warmed up the engine, the plane and their insurance underwriter. Pilots in Alaska in the 1920s all the way up through the 1950s and into the '60s sometimes had to put up tents over at least their engine and then build a fire to warm things up.

Sam O. White, one of the first flying game wardens in Alaska, suffered a broken oil line flying in a remote section of Alaska one winter in the 1930s. He quickly landed his ski plane on a flat section of a snowy ridge, jumped out, got a fire going, fixed the broken oil line, and then spent several hours shuffling around on snowshoes to pick up all the snow stained by his oil leak. He then laboriously boiled off the snow and reclaimed most of his oil, which he poured back into the engine and took off. I know this because Sam O. White was from my area of Maine, and his great-grandson has a camp near mine.

These events were vaguely in the back of my mind as I went through the one minute of labor needed to plug a heavy-duty extension cord into the hangar outlet and plug the other end into the resistance heater installed on my Tri-Pacer. As I closed up the cowling and started to put the thickly padded thermo cover on---to hold all the nice heat in---I saw blue smoke rising from the engine. What? I stepped back and looked things over. Is the plane on fire? I unplugged the extension cord and got the fire extinguisher out of the cockpit.

My rented open-faced hangar is one in a row of hangars. I could see six or seven planes on this side, probably the same number on the other side of the old stick-frame, aluminum-sided construction. I had no idea how old the building was. It looked like it had been here for a long time, but architecture ages fast in the sun, wind and oil stain of airports. I didn't want to stand in front of 14 pilots and tell them how I started the fire that burned up their airplanes. But the desire to warm up my engine was slightly stronger than that fear, so I plugged the extension cord in again and waited.

The fumes and blue smoke reappeared, but this time I just stood and watched. After 15 minutes or so---it felt like an hour---the smoke died down. I felt the engine casing; it was no longer ice cold. I put the thermo cover back on and walked a tenth of a mile to the airport terminal shack for a coffee---all the while keeping an eye out for a plume of black smoke coming from the direction of my hangar. Satisfied that all was okay, I finally drove the 40 miles back to Phillips. The next morning, I quickly scanned the local paper just to assure myself nothing untoward happened at Central Maine Airport during the night. This "uh-oh" feeling happens every winter as I plug the plane in for the first time. There's always a bit of oil on the bottom of the engine after the summer's flying, and every winter, I have to stand there for a bit and watch it evaporate before I'm satisfied I can leave the plane plugged in and drive home.

The process of clearing ice and snow from in front of the rented hangar evolves over the course of the winter. After the first few storms, I arrive at the airport, get my snow scoop and shovel, and clear a nice wide path in front of the plane, usually about 3 feet wider than the plane's wheelbase. As winter deepens, along with the snow, this nice wide path shrinks to just barely the width of the wheelbase.

By February or so, the snow now having been cleared more times than I can remember, and the snow on the hangar roof having fallen off on days I wasn't there, leaving behind a foot-high ridge of solid ice, this path is now reduced to three-wheel ruts painfully sculpted with a pick and ice scraper. In fact, the phrase "clearing ice" is a bit comical: no one actually clears ice. You chop away at it until you are ready to collapse, and then you live with what's left.

By early March, even the wheel ruts seem too much to do, and the ice mound in front of the hangar is shaved down just a tad, allowing me to start the plane in the hangar and drive it at near-full-throttle up and over the ice and out to the clear, sacred space where the airport plow truck has done its symbolic work.

Getting the plane back into the hangar, usually at night, means somehow getting it up and over that ice dam. This can't be done with the muscles of one human being. I pondered taxiing the plane face-first into the hangar, but that would just set up the problem of getting it out the following week. I bought a manually operated winch and installed it in the back of the hangar. I don't know the mechanical advantage of standard winches, but this one required 10 to 15 full rotations just to get the airplane's attention. The Tri-Pacer has a great sturdy hook under its tail, making it easy to winch it in backward. But the process takes the better part of an evening in summer or most of a night in winter. On the drive home, I could still feel my arm going round and round and round.

I've always carried a survival kit in the Tri-Pacer; it seems like an optimistic thing to do. It consists of a narrow-cut mountain backpack and a separate nylon bag with a pop-up two-person tent, a tarp and one of those squashable sleeping bags that fold to the size of a football. In the pack are a change of clothes, some thin wool underwear---which can keep you reasonably comfortable in cold or wet weather---a couple pairs of socks that are a combination of wool and synthetic fibers, a wool watch cap---very important---a good hank of nylon rope, three small sealed tins of tea, and three or four of those old-fashioned liquid-filled cigarette lighters.

Living in Maine, I used to keep one of those liquid lighters squirreled away in every jacket I owned. TSA agents gradually confiscated most of them as I tried to board commercial flights. As I write this, I suspect there are TSA agents here and there in the Northeastern part of the United States still lighting their barbecues with my lighters.

Probably the most important item in the survival backpack is my huge Gurkha knife, or Kukri. This looks like a big Bowie knife with a down-curving 30-degree angle in the middle of the blade. It works well as both a knife and a small hatchet. I can easily cut down small trees and chop them up for firewood or make pointed staves for a shelter. Also, I've always kept a first-aid kit and a quilted, three-quarter-length coat, good for sub-zero weather, tucked away on the shelf behind the back seat.

As I said, I don't carry a firearm on board my plane, though some Maine pilots do. While you wouldn't need one to scare off a grizzly in these parts, a Maine game warden friend explained to me that firearms are the best signaling device you can have. The sound of a bear whistle, or one of those contrived "survival whistles," doesn't carry very far in the woods---and you need both of your post-crash lungs in good working order to use one. The sound of a handgun or a rifle carries for miles on a windless day, and you need but one working finger to use them.

If you feel you need to have a weapon in your survival kit, the best choice is a shotgun. Everyone thinks they can handle a handgun because, well, they are easy to pick up and dry shoot. But unless you practice regularly with one, you're not going to hit anything with it when you need it. Imagine yourself lying in the woods in a haphazard shelter, one leg broken and the rest of you not feeling that well. Your luck bagging a rabbit with a .22-caliber pistol is somewhere close to ridiculous. I own a .44-caliber Civil War naval officer's revolver. It has an imposing 8-inch barrel, and, with its black powder charge, packs a pretty good wallop. But I don't carry it in the Tri-Pacer---it would extend my takeoff distance some 50 yards.

Of all the hazards of flying in winter, the hardest one to detect is baggage creep. It occurs over a period of several winters until, one sunny February morning, you realize you've been lugging 75 pounds of stuff with you in the back of the plane. In addition to the tent, sleeping bag and survival backpack, you now have on board a big plastic bin full of tools; hydraulic fluid (for the brakes); duct tape (for the wings, remember?); extra inspection port covers (mine pop off now and then, usually on takeoff); a nylon bag full of heavy tie-down stakes and rope (lots of small airports don't have tie-down ropes anymore, either because the ones they had were worn out or their insurance broker came around and pulled them: "Sorry that your airplane flipped over in the wind last night, but those weren't our tie-down ropes"); wing, windscreen, tail and cowling covers; and a 10-pound jumper cable with a special fitting on it for starting a Piper.

At some point, you have to inventory all this stuff and decide on what you really need because it's getting out of hand. Come some blistering hot summer day, all this survival gear and extra tools are going to prevent you from clearing the trees at the end of the runway. Of course, if that does happen, you'll have everything you need to survive.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox