A Legendary Flight Experience

Taking an impromptu media excursion with pilot Bob Hoover was a ‘thrill of a lifetime.’

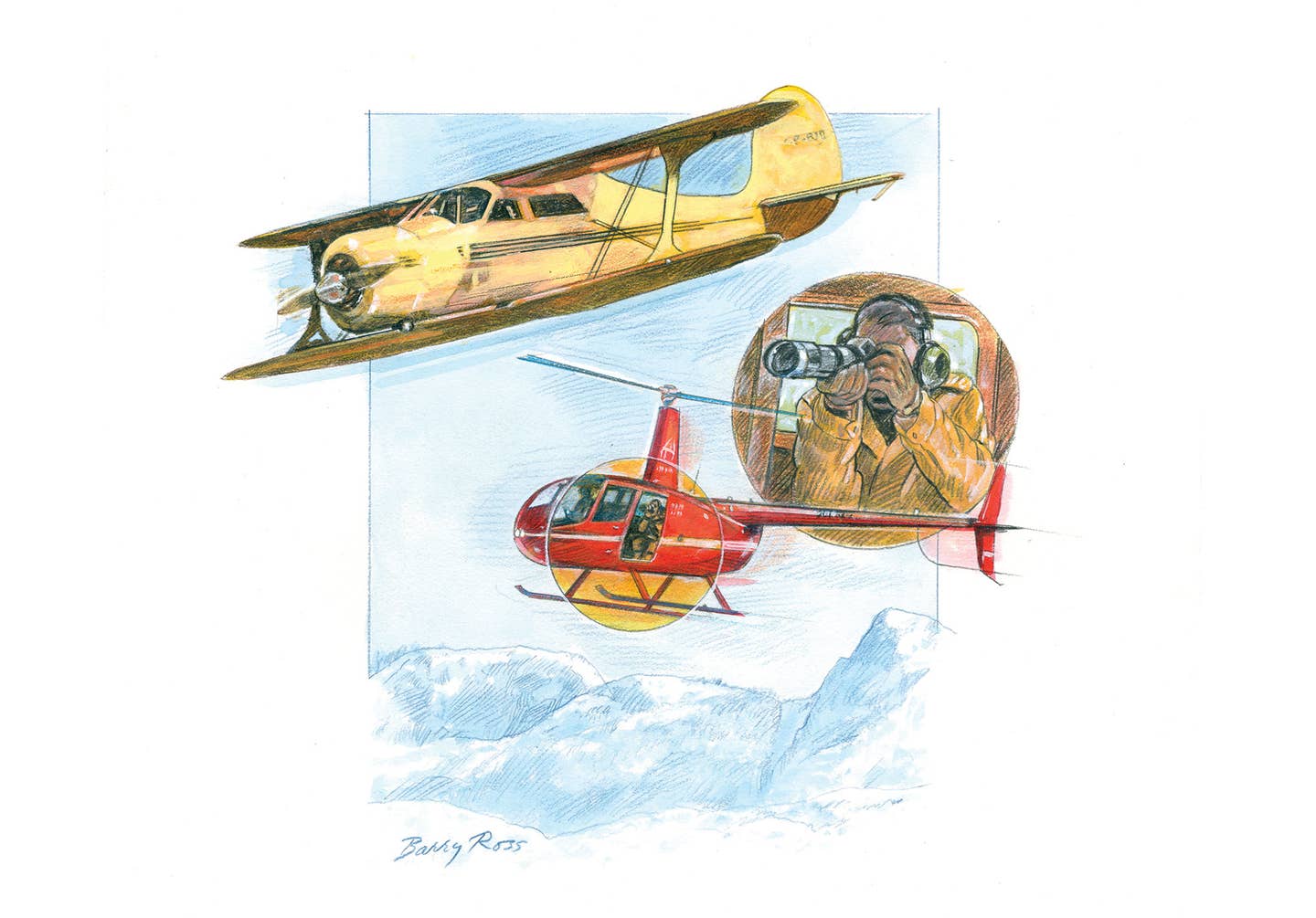

Illustration by Barry Ross

“Serendipity can sometimes lead to indelible memories. I was fortunate enough to be on the receiving end of one such event on a sunny day in fall 1982 by simply being in the right place at the right time.”

I was 25 and had just spent three months working as the sound engineer for The Western Stage summer theater at Hartnell College in Salinas, California. The gig required me to find all the music and sound effects needed for the plays we performed that year, as well as splicing tape for the reel-to-reel machine, setting up speakers and mixer boards, and running sound cues during the shows.

At the end of the season I found work at a local TV station, KCBA, which at that time was broadcasting in Spanish. Along with my friend Marc, a scenic designer with whom I had worked on several occasions, we built the set for the station’s news show and then did some construction at its transmitter site in the nearby hills.

One morning before heading to the transmitter, the news director asked if one of us would like to take a media flight. He needed someone to assist the cameraman by lugging around the bulky VCR, which in those days weighed around 50 pounds. It felt like a big rock over my shoulder. But being the son of a U.S. Air Force pilot and a lifelong aviation enthusiast, I readily volunteered to go along.

About my father: His first great love was baseball, and he dreamed of playing for the Pittsburgh Pirates. Indeed, he made one of their minor league squads and yearned for a chance of going to the major leagues. But when that didn’t pan out, he gave up on being a ballplayer and enlisted in the Air Force. He was nominated for and attended Officer Training School, where he earned his wings. Sadly, while flying an interdiction mission in Laos on November 10, 1966, his Douglas A1-E Skyraider was hit by ground forces, and he perished before he could pass along his flying skills to me. But growing up amid the roar of propellers and jets had planted in me the seed of a lifelong love of all things aeronautical.

October 2-3, 1982, was the weekend of the 2nd annual Salinas International Airshow, which still goes on to this day, although it’s now called the California International Airshow. Our videographer and I—and one from another local TV station—arrived at the Salinas Municipal Airport (now KSNS) and were led to a green-and-white North American Rockwell Shrike Commander 500S bearing the name of its sponsor, Evergreen International Aviation. It could carry a crew of two and four passengers at a cruise speed of 175 knots, or about 200 mph, at a service ceiling of more than 19,000 feet. The very same craft is now enshrined in the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. One of these Shrikes, with the military designation of the U-4B, was the smallest ever Air Force One, carrying President Dwight D. Eisenhower, and the first to wear the now familiar blue-and-white livery.

Introductions were quickly made, and the pilot, none other than the legendary Bob Hoover, gave us a walk around the plane to familiarize us with the twin-turboprop, high-wing aircraft. The Shrike was slung low to the ground, so that Hoover’s lanky 6-foot-2 frame stood nearly as high as the top of the wing. After the inspection, we boarded for a flight around the Salinas-Monterey area, during which our cameramen would be gathering footage for the evening news shows. I was seated directly behind the renowned pilot.

The Salinas Valley stretches approximately 90 miles southeast from the Monterey Bay near Castroville, between the Gabilan and Santa Lucia mountain ranges, and is known for being one of the most productive agricultural areas in California. The verdant patches below, framed between the towering hills, provided our cinematographers with some great scenery.

Rapidly and efficiently, Hoover started the airplane and prepped for departure, briefly explaining some of its systems for the benefit of us earthbound neophytes. In short order we were accelerating down the runway, ascending into the cerulean sky, climbing over the city, and being treated to a breathtaking view of the expansive ocean to the west.

Once we reached the proper altitude, Hoover made several steeply banked turns, showing off his skills as an aviator as well as the agility and capabilities of the dependable Commander. Hoover then pulled the aircraft up into a sharp climb that culminated in a zero-G stall maneuver, making the airplane and its wide-eyed passengers weightless for a brief moment. As he eased the nose over to regain airspeed, the heavy tape recorder in my lap rose gently into the air before settling back on top of me as gravity took over once more.

Next, Hoover explained that he wished to demonstrate how this airframe could fly perfectly well on one engine, and he abruptly shut down the left powerplant. This was a little disconcerting to us passengers, but we had to assume he knew what he was doing. After making a couple of wide, sweeping turns over the fertile valley, Hoover announced that the airplane could fly just as well with no power, and he proceeded to shut down the right engine.

While the confidence he had instilled in me with his flying prowess was uncompromised, I could sense the cessation of the growling from the twin Lycoming turboprops caused a good deal of uneasiness for the others on board.

Like a sailplane, we glided silently in a lazy, downward spiral until we were lined up with the runway at the correct altitude for our approach. We crossed the threshold just a few feet above the tarmac, and our intrepid pilot announced, “This is what I call the Tennessee waltz.” Hoover gently banked the plane to the left, dropped down to touch that landing gear, then pulled up and reversed the bank to do the same with the right. After alternating sides four or five times, he settled the noiseless aircraft on the runway, applied the brakes, and diverted onto a taxiway. We then coasted into the proper parking spot, all without ever having restarted the engines.

It was the thrill of a lifetime for me. I subsequently saw Hoover fly many times at the National Championship Air Races at Reno-Stead Airport (KRTS) in Nevada, and each time it brought back the happy memory of that sparkling day in Salinas.

Hoover, who died in 2016 at age 94, was a World War II fighter pilot, test pilot, flight instructor, and airshow performer. On February 9, 1944, his damaged Supermarine Mk V Spitfire was shot down off the coast of southern France, and he was taken prisoner. Sixteen months later, during a riot in his prisoner of war camp over the deplorable conditions, Hoover scaled a fence, escaped, stole a German Focke-Wulf Fw 190 reconnaissance airplane and flew to safety in the Netherlands.

For years he flew his yellow P-51 Mustang, named Ole Yeller, at the Reno Air Races, acting as marshal and race starter. I’m sure Hoover is remembered by thousands of fellow pilots, flight students, and airshow enthusiasts. Even back in 1982, he held the status of a living legend in the aviation world. Among his other accolades he flew the chase plane, a Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star, for Chuck Yeager’s Bell X-1 supersonic flight on October 14, 1947.

But I’ll always remember him for that thrilling ride in the Shrike Commander.

Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of Plane & Pilot magazine.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox