Hangin’ Out in Austin

By the summer of 1983, I had finished my junior year of ROTC, and our old neighborhood gang was reunited again. Larry Leonard and I roomed together our college freshman…

[Illustration by Barry Ross]

By the summer of 1983, I had finished my junior year of ROTC, and our old neighborhood gang was reunited again.

Larry Leonard and I roomed together our college freshman year at the Castilian dorm, where I met my future wife, Karin. Before starting our senior year, Larry and I moved into the same Austin apartment complex, each in a one-room efficiency, and Michael Rafferty was in his sophomore year at the University of Texas.

Driving through the west Austin hill country one late summer day, Michael and I spied a hang glider for sale in a front yard. We were both aviation enthusiasts and inspired to take up hang gliding after watching James Bond in the opening scene of Live and Let Die. Although we didn’t buy that particular glider, the owner put us in touch with the Austin hang glider club.

The club was run by two Steves—Steve Burns and Steve Stackable, a 1975 U.S. motocross national champion. “Stack” was the ultimate cool dude. This wavy-haired motorcycle star had raced in the Houston Astrodome in the 1970s.

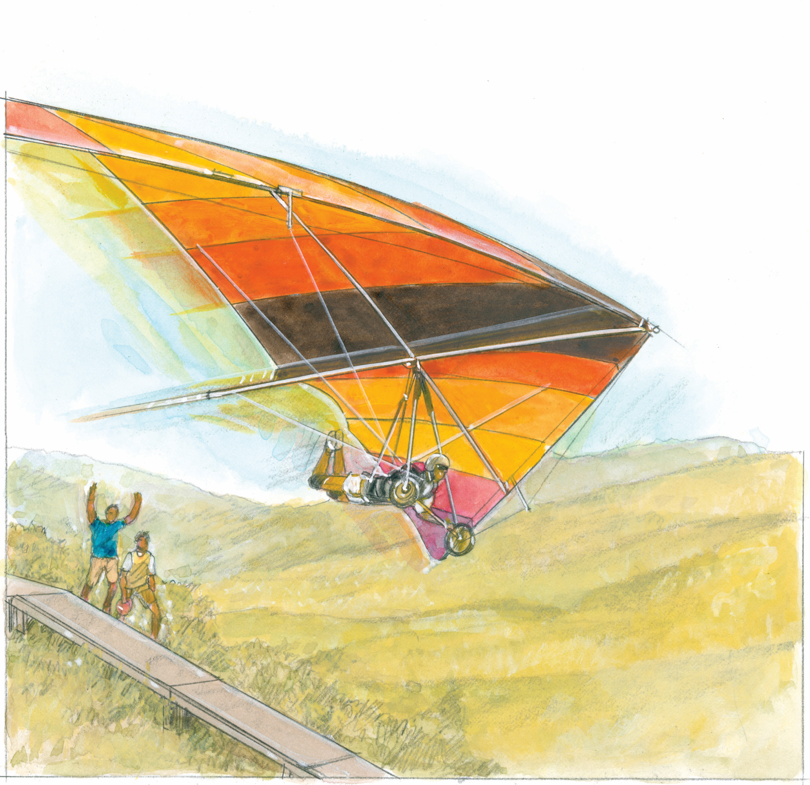

Michael and I entered Austin Air Sports’ small wooden shop and asked about hang-gliding lessons. Through Burns’ connections, we found a great deal. Michael and I split the $800 cost of a 1980 Spirit Electra Flyer, featuring an innovative crossbar, making the large, 200-square-foot hang glider pretty nimble and maneuverable. It had multicolored, earth-tone panels with brown in the center, then orange, tan, yellow, and red ones extending out to the purple wingtips. The entire disassembled glider was relatively easy to transport, fitting into an 18-foot blue canvas bag, about 2 feet in diameter.

Launching a hang glider required a hill to run down, and that meant we needed a four-wheel-drive vehicle. I bought my brother’s green 1978 Subaru BRAT, a tiny two-seat pickup truck with a four-speed manual transmission and a 4-foot bed covered by a white camper shell. Once loaded, our “glider in a bag” extended 2 feet in front and behind the 14-foot truck, but we were in business.

Learning to fly a hang glider required a mastery of taking off and landing first and foremost, much like learning to fly any airplane. We only needed a small hill, and for that, Austin Air Sports used the football field sunken in a shallow bowl at Murchison Middle School. Our beginner’s lessons reminded me of Charlie Brown skiing down his pitcher’s mound. The flights lasted only seconds, but they suited our needs.

Our Spirit glider came complete with training wheels mounted on the control bar. I stepped into the blue harness that ran from shoulders to crotch like an old-fashioned men’s swimming suit. Our knee-hanger harness had two thick 6-foot ropes shrouded in material stitched into it at my shoulder blades and attached by wide Velcro straps just below my knees. This simple style of harness kept our legs and feet free to run down the launch ramp. The two thick ropes, held together with a carabiner, then hooked to the glider frame above and behind my shoulders.

Once safely buckled in and with my white half-shell motorcycle helmet in place, I hoisted the triangular control frame assembly onto my shoulders. My arms were draped around the downtubes of the triangle and my wingtips extended out 17 feet in each direction. I ran a few steps down the small hill, and the large wing became airborne within seconds. For the initial training, my only goal was to fly straight ahead into the football field and belly land. This allowed the wheels to touch—and me to coast to a stop. After a flight shorter than Orville Wright’s famous one back in 1903, I stood up and unhooked the carabiner. Holding onto the pointed nose of the kite, I pushed it up the hill for another go.

Larry joined Michael and me, and we each practiced numerous takeoffs before learning the art of flaring the large kite for a normal landing. As the glider approached the landing zone, I pushed gently forward on the control bar, raising the nose but not enough to climb back into the air. This allowed for a feet-first landing, like a duck settling on water. If I pushed too aggressively on the control bar, I risked climbing 10 feet up in the air, stalling the wing, and crashing to the ground. Hang glider pilots have broken their legs from this sort of botched landing.

After a few weeks of Charlie Brown pitcher’s mound practice, we were ready for a real hang glider flight. The nearest suitable launch location in flat Texas was a 400-foot hill on Packsaddle Mountain, an hour and a half west of Austin between Marble Falls and Llano. Michael and I strapped our bagged glider to the top of the BRAT and set off for the Texas Hill Country behind our instructors, Stack and Steve.

The little 4-cylinder truck bounced its way along a 2-mile dirt county road off Highway 71, finally turning off at the base of an outcropping where two hills merged into one, raised at both ends with the right side higher than the left, giving it the appearance of a horse’s packsaddle. Our launch point was the southern, higher hill, and the truck tackled the rutty dirt trail up to the 400-foot summit.

With the kite fully assembled and my harness and motorcycle helmet donned, I carried it on my shoulders to the wooden launch platform, which was painted like a gigantic Texas flag in red, white, and blue. Stack said the first few attempts would just be sled rides, a simple flight with only mild S-turns from the launch platform to the cow pasture directly below. Given the increased speed of this flight versus the small football stadium hill, I was instructed to just make a belly landing on the training wheels until I gained more experience.

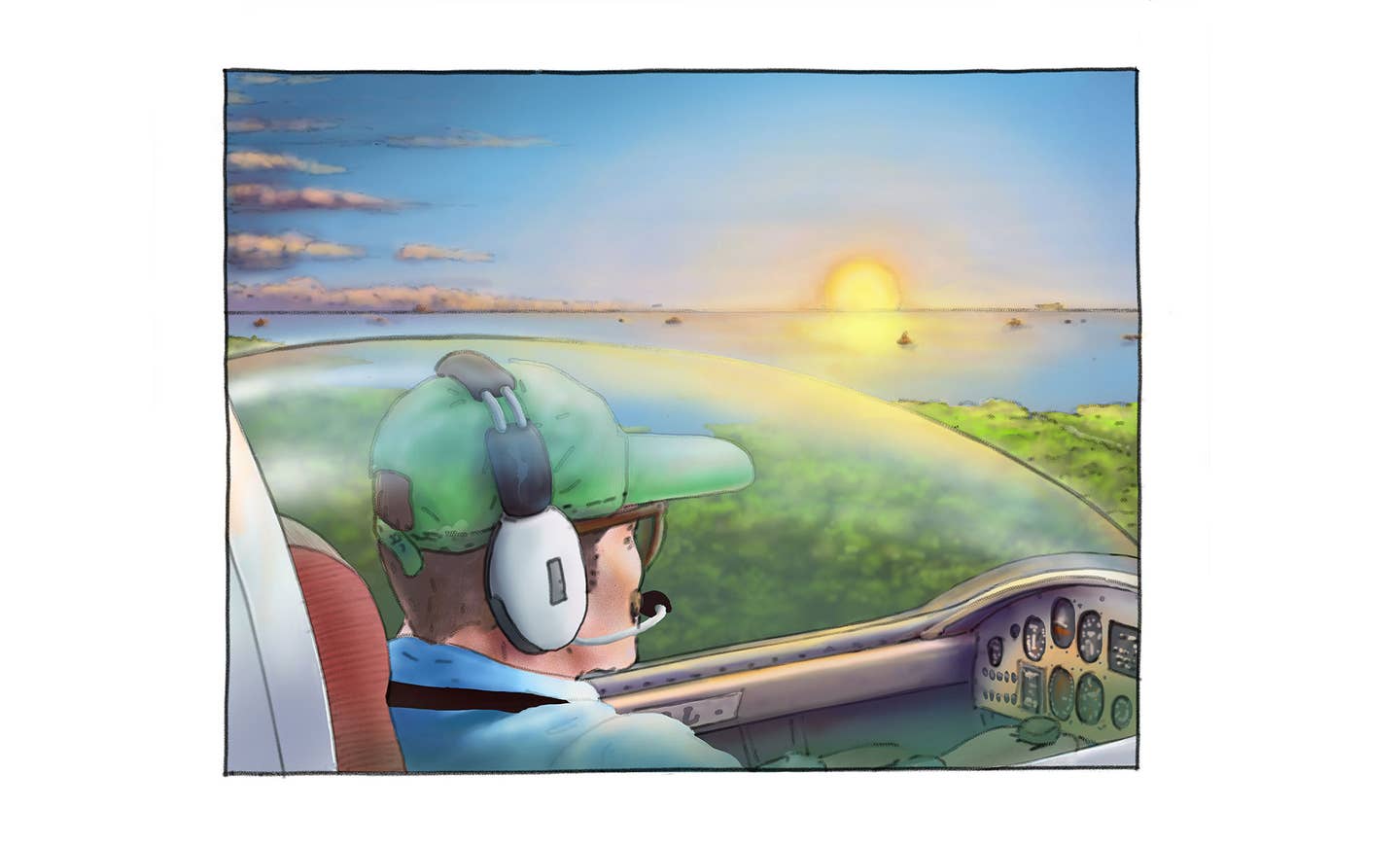

Balancing the kite on my shoulders, I jogged down the 10-foot ramp and was airborne after just three steps. The wind whistled in my ears as the craggy hillside fell away below. Ahead lay a vast pasture used for grazing cattle, which made for an easy landing zone. My inaugural flight lasted perhaps a minute, and I glided toward the dry, brown, summer grass for a soft landing.

Now came the tedious part. During my short flight, Michael drove the BRAT down the bumpy road and into the pasture, and together we partially disassembled the kite, folding the wings together along the central spar and taking apart the aluminum triangle. Hoisting our kite back onto our trusty little pack mule, we drove back up the hill for another flight. Lather, rinse, repeat. Early on, Michael and I would each take three short flights then turn over the kite to the other person for their turn to practice. It became quite a long day for just a bit of flying, but the experience was exhilarating.

After a few more sled rides, I began to get a feel for the handling of our Spirit glider from takeoff to landing. I started to add gentle turns to the flights, cruising back and forth along the hillside in what is called “ridge lift,” created from the southerly wind flowing toward Packsaddle Mountain. As long as the breeze blew and I stayed in a thermal or ridge lift, the glider stayed airborne indefinitely. There were just two things limiting our flight time: Michael was waiting for his turn, and while gliding I was in a front-leaning-rest, push-up position, which became tiresome.

Typically, our flights lasted about 20 minutes, and this was plenty of time to take in the rustic sights of the Hill Country. Like a hawk scanning the land below, I could see the Colorado River to the north and east, divided by dams to form lakes Buchanan, LBJ, and Travis. To the south, I saw Highway 71 snaking its way west toward Llano, and miles and miles of cedar and scrub oak-covered hills. Gliding was very peaceful, with only the soft hiss of the wind in my ears and the creaking and clinking of the aluminum glider frame.

On occasion, our desire to fly like a bird was enhanced when we were shadowed by a pair of turkey vultures that launched from the surrounding trees to follow our kite. As the pilot, I was rarely aware that I was leading a formation of birds. With the large black birds following just aft of my wingtips, I couldn’t see them, but they made for some excellent photographs.

Communing with nature occurred not only during flight but also during the evening landings. Our landing zone was the preferred dining spot of the roaming herd of cattle. Around 5 p.m., as the sun began to set and we were getting in our last flights, about 30 black cows began grazing right in our landing zone. Just as aircraft used to buzz sheep or cattle, I too took part in that ritual.

After cruising in the hillside ridge lift for a half hour, I flew away from the hill and out of the lifting wind currents to begin a shallow descent to the brown, grassy field below. I gained enough speed to allow for a “go-around” if things didn’t look right before landing. I whistled over the uninterested bovines just 5 feet above their backs. Once clear of the munching moos, I pushed forward on the control bar, raising the nose slightly. I then circled back to a clear grassy spot for a flare, touched my feet to the ground, and shouldered the kite. I loved the calm, thrilling experience of hang gliding.

Unfortunately, my flights didn’t always go as planned. One evening, the winds started to pick up as our day came to an end. Wanting to get in just one more flight, I suited up for a last run. I ran down the launch ramp and became airborne just as a gust of wind hit my left wing and blew me immediately toward the radio tower guy wires about 50 yards to the right of our ramp. I immediately shifted my position to the left corner of the control bar and threw it up and to my right, trying to counter the wind with a hard left turn. Fortunately, my right wingtip missed the guy wires by a few feet, and I cruised away from the tower and into the hillside updraft.

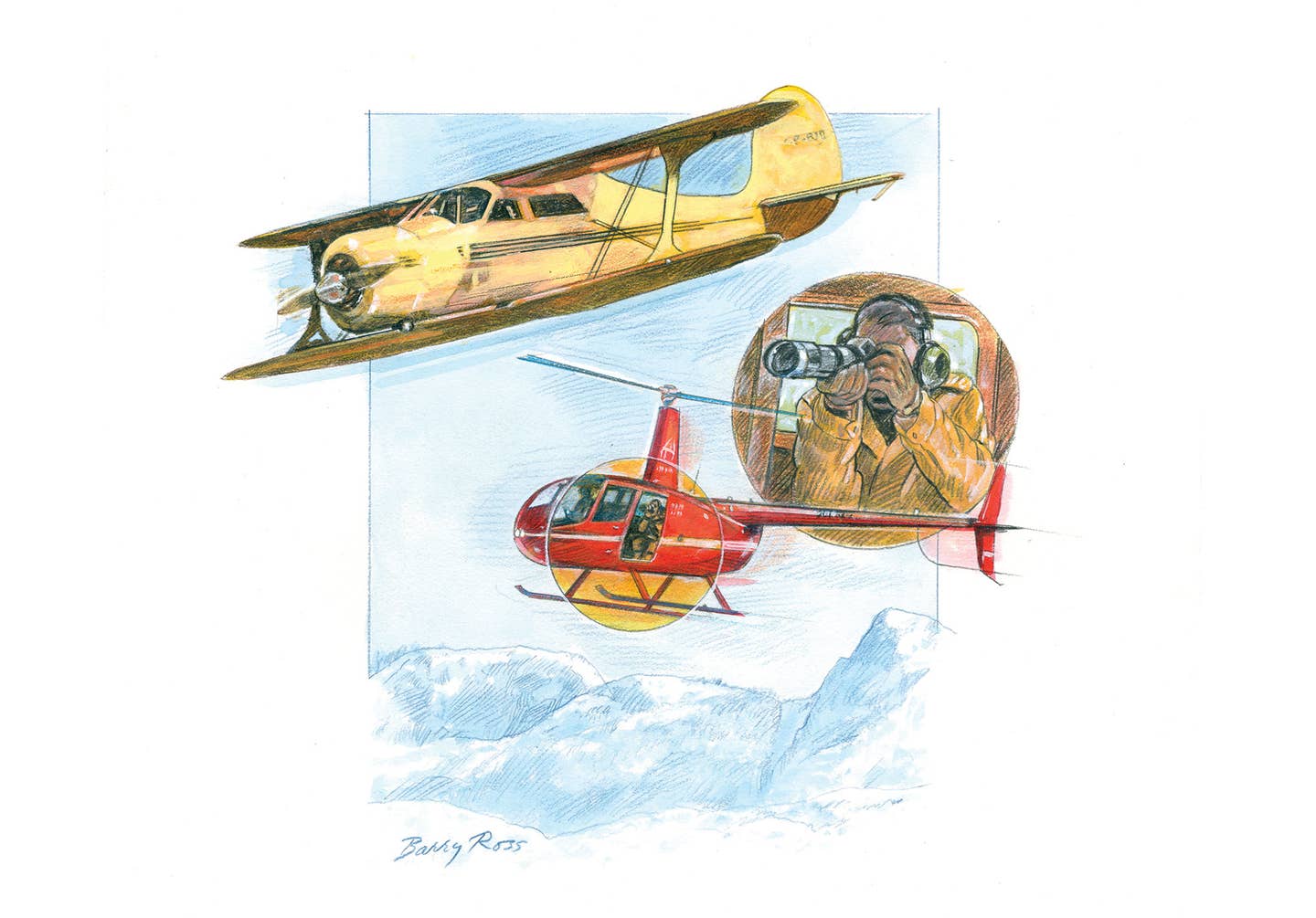

My second incident involved a revolutionary way to launch hang gliders by towing them behind a powered ultralight. Just as airplanes tow sailplanes in soaring, a French company pioneered a tether system for its powered gliders that we used to launch us from the pasture. Part of the three-ring release assembly included a weak link designed to snap if too many G-forces were pulled by the trailing glider. This way the powered leader would not drag a flailing kite, pulling them both back to the ground. Larry and Michael each took a turn, running with the kite for a few feet as the power glider gained speed and towed them safely to altitude for a smooth flight.

- READ MORE: Try These Low-Cost DIY Hangar Projects!

I suited up in the harness and helmet and gave the towing tricycle glider a thumbs-up that I was ready. As he increased the thrust of his small propeller, I walked then jogged as he gained speed. Just like launching from our hillside ramp, I was airborne quickly, but the cool sensation this time was that I was only a few feet above the grass. I enjoyed the low-altitude cruise at grass-top level as the power glider gained speed and altitude. We flew up to 200 feet, and he began a gentle turn to the left. I must have been looking down or off to my right at the scenery because I didn’t notice his turn, started mine too late, and didn’t aggressively get back into position behind him. Within a few seconds, my kite was straining the tow rope and the weak link snapped as designed.

I now needed to make a quick landing back at the cleared field behind me. It’s a situation I had been trained for in flying small planes, just like an engine failure after takeoff. Needing to immediately turn back to the landing zone, I continued my wide left-hand turn and saw trees and a power line between me and the pasture. Without the ability to add power, I could only hope my descent rate would clear the obstacles as the trees and power line loomed closer. Luckily, my feet cleared the power line, and I successfully landed in the field. So much for that adventure. I was pretty shaken up by that episode, knowing I had caused it by getting out of position. While Michael would go on to enjoy years of hang gliding and soaring in a sailplane, I decided I would stick to powered flight. Give me an engine any day.

Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of Plane & Pilot magazine.

Want to see more stories like this in print? Subscribe Here.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox