Getting Even

A close call in the early 1960s in an unfamiliar PA-12 stressed the importance of preflight inspection.

Editor’s note: Read the prequel to this story in this issue’s Lessons Learned.

On my first solo cross-country, I had to land in a cow pasture due to an engine failure. The plane had just come out of a 100-hour inspection by the flying club’s mechanic. The mechanic flew out and fixed an oil line that had chafed through. The mechanic asked me to tell no one about what had happened.

After the plane was fixed, I flew it back to Lawson Army Airfield (KSLF) at Fort Benning, Georgia. The mechanic flew the airplane he’d flown back as well. After we landed and were tying down, the mechanic came over to me and said, “Thanks,” and that he “owed me one.” I thought nothing more about his statement until the day before I left Fort Benning.

I continued to operate the flying club’s planes while waiting to be discharged. I was to get my papers on Friday, so that I could leave the Army. I finished clearing the post on Wednesday. On Thursday, I had nothing to do. I decided to go flying. I went to the clubhouse to check out a plane. I was hoping for one of the PA-18s, but the only airplane available was the PA-12. I filled out the paperwork for a local flight, grabbed the keys, and headed out.

The PA-12 was the only plane on its part of the ramp. Not being as familiar with the PA-12 as I should be, I did a preflight inspection, the same as I would do on the PA-18. The Super Cruiser was full of gas and oil. I untied the plane, pulled the chocks, climbed into the pilot’s seat, and fastened the seat belt.

I sat there for a while, knowing this may be the last time I flew anything for quite a while. Then and there, I decided I was going to make the most out of this flight and have fun.

With mixture rich, throttle cracked, carb heat off, and master switch to both, I hit the starter, and the plane roared to life. I checked the instruments, and all were in the green. I sat for a few moments listening to the engine. OK.

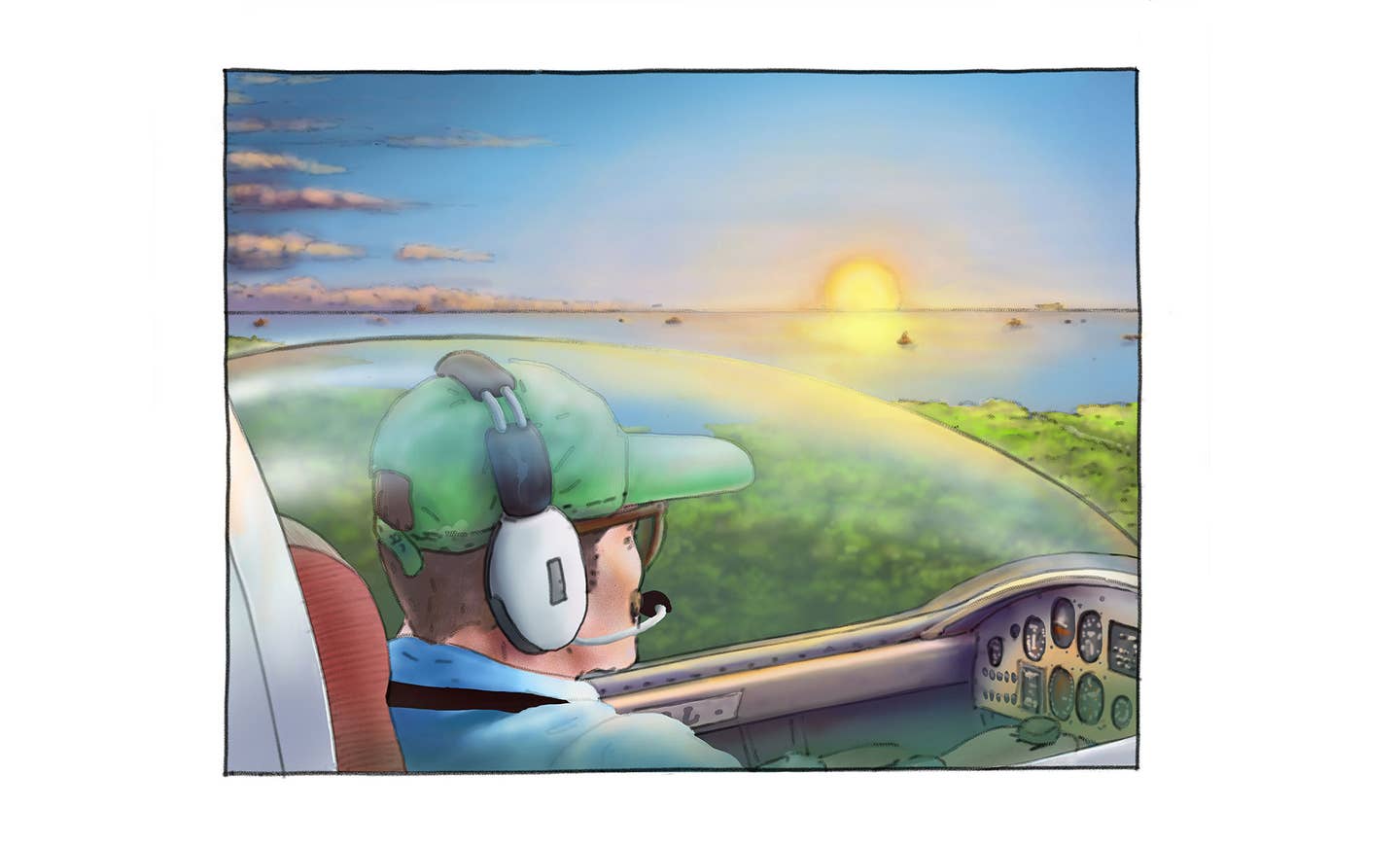

I was ready to have some fun in the practice area. I called Lawson Tower and was cleared for taxi and mid-runway takeoff on Runway 15. I then did my run-up. All was good, and I taxied out. After takeoff I turned for the practice area. After clearing Lawson airfield traffic area and Fort Benning, I dropped down to treetop level to have some fun. When I reached the designated practice area, I climbed to 3,000 feet. I did some tight turns and gentle stalls, both power on and power off.

For the next stall, I pulled the nose up a lot higher than normal with power off. The plane broke hard into a stall. As the nose passed through the horizon, I let off on the back pressure and pushed the stick forward to pick up airspeed. As it built, I added power and eased the stick back. To my surprise, the stick only came back a small way and stopped solid. I was still in a pretty rapid descent. I pulled the power back and frantically tried to tug the stick back several times to stop my dive and level out.

I could see there were no obstructions to the stick’s movement in the front. The problem had to be in the back seat. While still in a descent, soon to crash into the trees, I turned to look. To my astonishment, I saw that the back of the seat, a square of half-inch plywood with one side covered with a foam-rubber pad and fabric, had fallen and was stopping the stick.

With one hand I lifted the back high enough to pull the stick back far enough to stop my dive. With one hand behind my back, I got the plane into a shallow climb and trimmed it out. Now under control and no longer in danger of crashing, I twisted around to fix the problem.

I lifted the seat back into place and saw there was a latch to hold it. I fastened it and turned around. With everything back to normal, I realized that, had I known more about the plane, the latch should have been checked in preflight.

Settling down, buckling my belt, and enjoying my climb back to 3,000 feet, I got to thinking about whether I could have slowed or stopped my descent with the trim tab. I flew around some, relaxing and reveling in the flight. I loved looking at the beautiful colors, farms, and animals on the ground.

After several minutes of just enjoying flying, I decided it was time to get the plane back to the club. I turned toward Lawson airfield, which I could see off in the distance, but decided I was going to do one last loop. I had never done a loop in the Super Cruiser, but I had done many in the Super Cub. I thought, what could be a problem? They fly about the same, although the Cruiser had 25 hp less than the Cub.

To overcome this, I thought if I entered the loop with a little more speed, I would be fine. Still on course to Lawson, I put the plane into a slight dive to pick up speed. At max maneuvering speed, I pulled back on the stick, adding full power. The nose passed through the horizon. I was looking at blue sky as it continued to climb. The plane and I were about to go over the top of the loop.

Then, suddenly, it stopped. I was hanging in my seat belt. The dirt and gravel on the floor and the contents of the ashtray were now making their way to the top of the cockpit. This lasted a couple of seconds until the right wing dropped, putting the plane into a roll. When it got to level, it stopped its roll, and at that moment, I heard a loud bang. The nose snapped up to a steep angle and the plane stalled.

As the nose passed through the horizon, I realized I was still holding full back pressure, and the engine was at full throttle. I immediately pulled back the throttle, and released back pressure. At the same time, all the debris overhead returned to its place of origin.

Dirt and ashtray contents were on my lap, shoulders, and hair. I was in a controlled descent.

I added some power, leveled off, and dusted off my clothes and hair. Turning back to Lawson, I looked around the cockpit and checked the instruments for anything out of order. I then checked all the controls, elevator up and down, ailerons right and left, rudder right and left. They all seemed to be working fine, but the plane just did not feel right. Maybe it was just my adrenaline.

I was cleared to enter downwind for Runway 15, and all went well on the landing and taxi to the club tie-down area, although the plane still just didn’t feel right.

After tying down, I did a walk-around and did not see anything out of order. When I got to the clubhouse, the mechanic was there. I filled out the required paperwork then walked to the mechanic to tell him what had happened. I also told him about how the plane did not feel right.

I followed him out to the Super Cruiser. As we looked up the little rise, we could see the top of the wings. The mechanic stopped and said he had to go back to the clubhouse and ground the plane. I asked how he could make such a decision without even inspecting it.

“Bob, do you see those three little bumps in the skin of the top of the right wing close to the fuselage? Those bumps are not on the left wing.” I could see what he was looking at. He went on to say something was broken, but he wouldn’t know what without removing the fabric.

He looked at me and said, “We are even.”

That was the last time I saw him. The next morning, I got my papers and left Fort Benning and the Army. I never did find out what broke. I often wonder how close I came to losing a wing by not adhering to the airplane’s limits.

Images: Adobe Stock

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox