Illustration: Barry Ross

According to Professor Google, I have acrophobia—an acute and, as it turns out, somewhat irrational fear of heights.

It likely started when as a very young kid when my stepdad took me onto a swinging bridge and then promptly showed me how it got that name. All I actually recall is hanging on with all my might and screaming my head off.

That moment must have been a turning point in my life because I’ve been afraid of heights ever since. I don’t do ladders, steep hills or even look out of a high-rise window. Indeed, as I have often shared with friends—I don’t even like being this tall, and I’m just 5-foot-6.

What if anything has that got to do with aviation?

I have been asked how it is that with that fear, you can spend so much time flying? The answer is: It just ain’t the same.

In fact, my first ride in an open-cockpit airplane, a Ryan PT-22, included loops and rolls, and I don’t recall having any concerns, just the joy of the ride. Several years later I got to fly a couple of open-cockpit aircraft, including a Fleet Finch 16B. Again, no issues—other than the cold, of course. I have a sensitivity to that as well.

I had never been in a helicopter, not for any reason other than the lack of opportunity. No one had asked me. Besides that, someone once told me that helicopters don’t subscribe to Bernoulli’s theory of flight. Instead, they just beat the air into submission.

As with most assumptions, I was to learn differently.

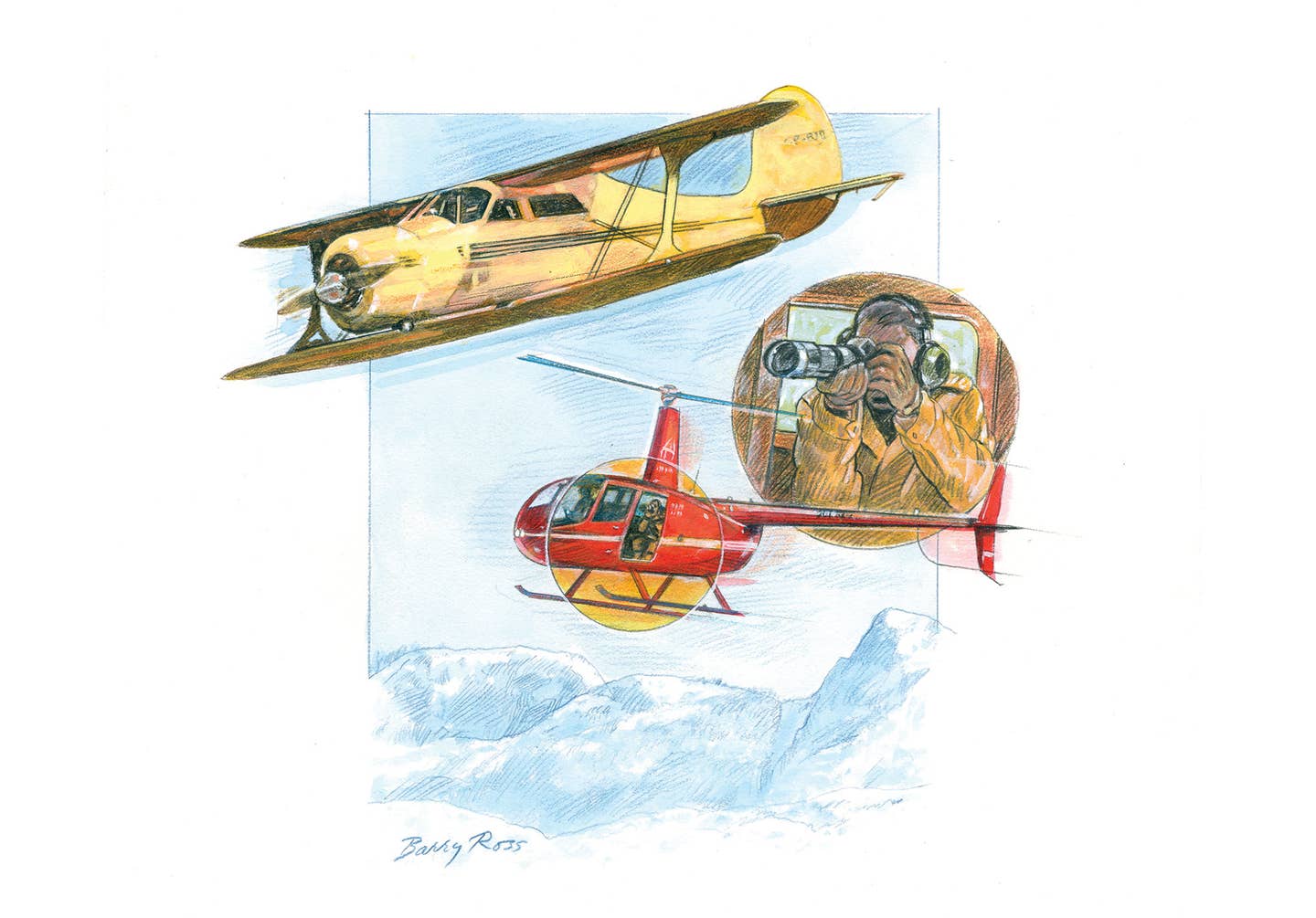

It all started with a phone call the night before telling me to be at the airport for an 11 a.m. briefing. The subject for the day was a previously planned photo shoot of a recently restored Beech Staggerwing. I needed to get some air-to-air shots of this “million dollar” antique for a proposed magazine article, and this was the first day that everyone’s schedules coincided. Even the weather cooperated as it was “calm, clear and a million,” a rarity in Canada’s coastal British Columbia in December.

The plan called for using a Robinson R44 helicopter as the camera ship. For this we needed two pilots with one as the observer and me, the photographer. Similar crew was needed for the Staggerwing, all volunteers and all experienced pilots.

The R44 was a four-place craft and since we could take the back doors off, I would have unrestricted sight lines. It should be perfect—no concerns about shooting through windows. It did make it mandatory that I be well secured to avoid falling out, which would likely upset me no end.

It seemed like a good plan, everyone inside and warm except the photographer—me. Give that some thought. Here I am actually considering flying in a helicopter with the doors off and me sitting just inside betting my life on the alleged security of a seat belt.

Everyone involved got together for the briefing as planned and the arrangements were confirmed for the important things such as communication, altitude, and direction of flight for the best light and the best backgrounds. Airspeeds were agreed to and radio frequencies were confirmed for communication between the aircraft and the helicopter should we need to reposition.

The owner would fly his helicopter with his pilot friend as the observer. There were two souls in the Staggerwing as well to ensure that enough eyes were on each other. To aid in the separation, I would be using telephoto lenses so that there was no need for close formation flying.

Same sky, same day was pretty much the order of business. Trust and careful briefing is critical for this type of flying as the consequences of a mistake or misunderstanding could be very serious. A misstep could ruin your whole day.

As the R44 cruises at 110 knots, it was agreed by all that the Staggerwing, being much faster, would form up on the helicopter as required. At my request, the pilot would yaw the helicopter either away from or toward the Staggerwing to help position the shots. While this made for a great shooting platform, sideways flight also put a lot of cold winter air into the back cabin.

The air was smooth with no wind to speak of. The local mountain peaks were in the clear with a coating of fresh snow, and they made for an excellent backdrop for the pictures of the bright yellow Staggerwing. All went well with good communication between each with both moving as I needed.

At one point, though, I became concerned when it appeared that I had a camera failure. I switched to a backup camera only to have the same issue. It seemed as though the shutters on both had ceased to function due to the cold air.

As it happened, both cameras were fine. But my hands weren’t. I was losing feeling in my fingers and couldn’t feel the camera controls. The pain from the cold quickly became unbearable.

However, as we changed locations or the Staggerwing repositioned, I took the opportunity to get the gloves back on and restore some semblance of feeling to my hands. With my hands warmed up, the cameras continued to work fine, and we were able to get the last of the pictures we needed.

Perhaps it was the distraction of photographing the Staggerwing. At no time did I notice that we were up high and with no doors. I still have what I now know is a clearly irrational fear of heights, but I can overlook it if there is the prospect of going flying.

I still don’t want to be much taller, but the distraction of photographing and flying seems to do the trick.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox