In the 1930s, pioneering English aviator Alfred “Lamp” Lamplugh penned the following profound words that we should review occasionally.

“Aviation in itself is not inherently dangerous. But to an even greater degree than the sea, it is terribly unforgiving of any carelessness, incapacity or neglect.”

This brings me to another profound phrase, the Boy Scout motto of “Be Prepared.” That is also what flight training is all about.

We learn all about aerodynamics, thrust, drag, lift, and gravity, study flight manuals, emergency procedures, and FARs, take oral exams and check rides, and constantly review everything we can find about flying. There is one thing though that we can’t study for—it’s luck, more precisely, bad luck.

Sure, when the engine goes silent, we pull out the emergency checklist and look at the fuel selector, carb heat, and whatever else can be rectified to get the engine running again. If it still remains silent, you are having a dose of bad luck, and you (quickly) have to get creative because every situation is different.

What if that freshly mowed hayfield isn’t at your 12 o’clock in 2 miles? What can you do to minimize your chances of injury during an off-airport landing?

Some years ago, a low-time private pilot hadn’t checked the weather and left Port Angeles, Washington, which was CAVU, for Seattle, where he was going to get fuel for his Cessna 150. Unfortunately, as he approached Seattle a large fog bank had formed in south Puget Sound, so he turned around to return to his familiar home base at Port Angeles, but by then it too had been socked in.

At this point, he became quite worried and called NAS Whidbey Approach Control, confessed his predicament, and asked if they knew of anything in the area that was VFR. They gave him a squawk and vectors to the nearest VFR airport they knew of. The pilot now nervously reported that he was almost out of fuel and wasn’t there anything closer. The plane was over the waters of Puget Sound, and Whidbey advised a vector that would bring him over land.

After numerous heading corrections, the pilot said his engine had just quit—and that was his last transmission. The plane was found in the forest the next day—the pilot didn’t survive.

What would you do in this situation?

In my Monday morning quarterbacking, I’ve often thought about that poor guy’s bad planning that led to his bad luck. Could he have survived a blind landing into trees or whatever if he’d trimmed his light Cessna 150, without fuel and only one person aboard, to minimum glide speed and kept the wings level rather than losing control and spinning in?

In my youth (1940s and ’50s) I built and flew model airplanes and dreamt of the time I could get my commercial certificate and a good paying airline job so I could afford a plane of my own (eventually I did own a Republic Seabee and a Piper Pacer). I finally got a handful of ratings and set out to land a flying job, but when that inevitable question came up—how many hours do you have?—305.4 wasn’t a very good answer.

The hours came slowly. I rented airplanes and took friends flying, gave free flight instruction and biennial flight reviews but finally told my wife to stay home and take care of the house and kids. “I’m going to Alaska to build some hours and will be back in a year,” I said.

I got my first real flying job with a Part 135 operator in Kotzebue, hauling charters to native villages and dirt strips around northwest Alaska. The winter days were short north of the Arctic Circle, and as I was shutting things down for the day, the boss came to the airport and asked if I wanted to haul three guys to Selawik, a village about 80 miles to the southeast. It was one of the few in the area that had a rotating beacon and runway lights. Since we were paid by the flight hour, I jumped at the chance to earn some extra bucks to send home.

The weather was doable, 1,500 feet overcast with the visibility at 2 miles in light, blowing snow. The terrain between Kotzebue and Selawik was frozen lakes and flat tundra, but even though there were no usable navaids in the area, dead reckoning should get us close enough to pick up the rotating beacon at Selawik.

My passengers were anxious to get home for a month after spending two months working as security guards on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. At each stop on the three legs of their flight back to Kotzebue, they found a bar and celebrated being with their families again soon. But I warned them—no more drinking on my plane, OK? They said all of their booze was in their luggage that I had put in the belly pod of the Cessna 206.

I buckled one of them in a rear seat of the 206 and the other two in the middle row, leaving the right front copilot’s seat empty. We took off and climbed to 1,000 feet and picked up a magnetic heading of 105 degrees and noted the time.

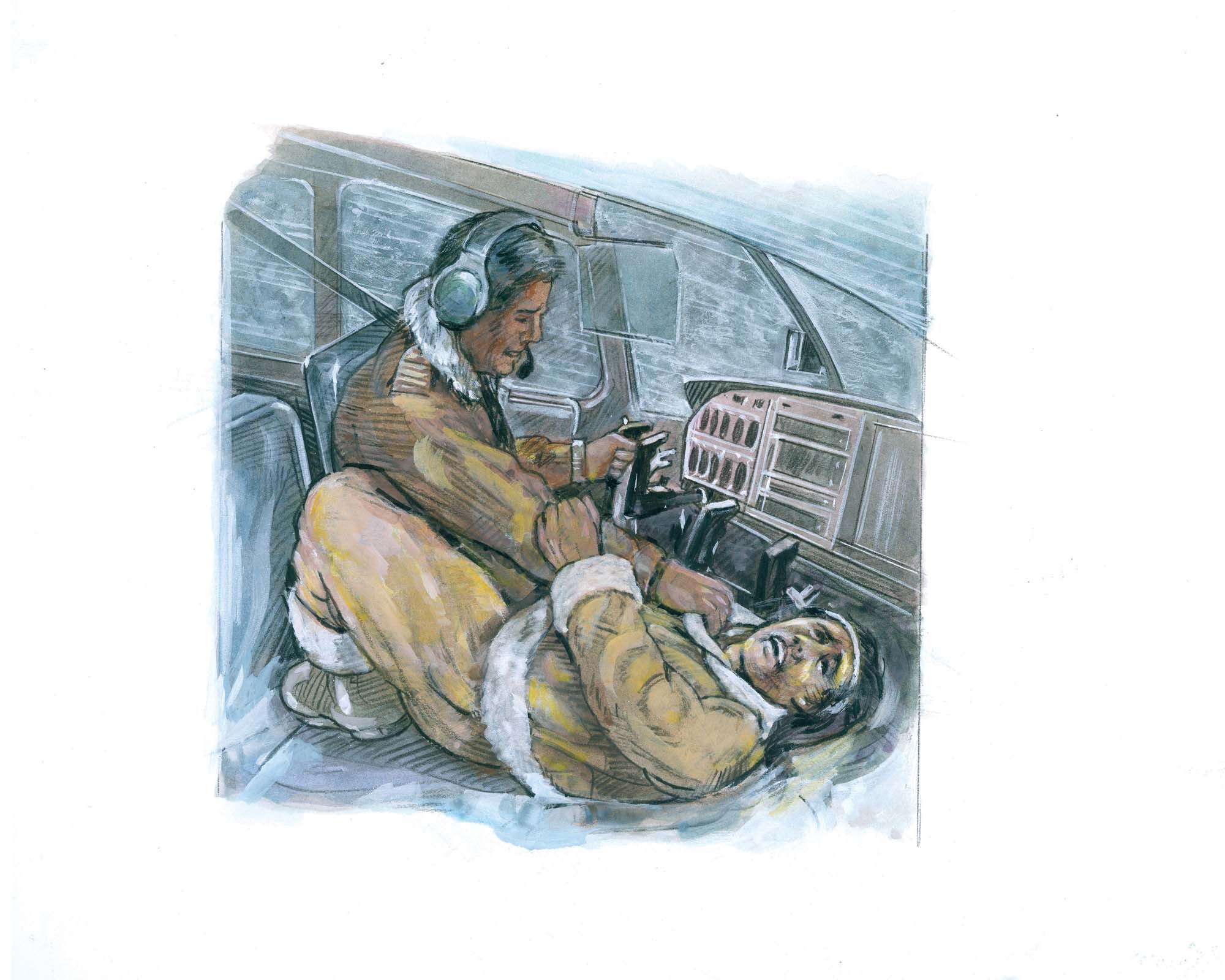

About halfway there, I felt some movement in the back of the plane but couldn’t figure out what was going on. Suddenly one of the passengers flopped over the back of the copilot’s seat headfirst, and his butt hit the copilot’s control wheel, pushing the plane into a steep dive. I’m not sure how I did it (adrenaline?), but somehow I managed to get him off the control wheel, turned around and right side up, and very undiplomatically said, “What the [expletive]are you doing?” He said, “Me help you fly.”

After climbing back up to 1,000 feet, getting back on heading and my heart rate returned to somewhat normal, I told him in no uncertain terms to put his seat belt on and not touch anything. He didn’t seem to like what I told him or take no for an answer. He said all the other pilots out here let him fly.

Under VFR conditions this might possibly have been OK, but in total darkness, without a horizon or lights on the ground, it’s impossible for anyone to keep a plane right side up if you haven’t had instrument flight training. Rather than risk a confrontation I said, “OK, but hold this heading and altitude. Do you understand?” He grunted something and within a minute we were starting into an expected spiral. I took the controls and leveled the plane, and after a few more tries he said, “You fly.”

I checked the DG and by that time we should have been able to see the rotating beacon—but still only darkness. I couldn’t figure out what was going on and told my passenger that if I couldn’t find Selawik soon, we’d have to return to Kotzebue. He mumbled something about the generator in the village being out. I was getting quite irritated with this idiot and asked why the hell he wanted to come out here if he knew the power was out. He said, “Maybe they put out lanterns.”

At this point, as if by magic, a very slight twinkle of light appeared out of the darkness ahead, then another. They must have been battery-powered lights shining through windows of the village houses. We flew over the village in the direction of the airstrip, and there were four dim lights, presumably two at each end of where the runway should be.

Since it was still snowing, I couldn’t use the landing lights in the air—they would just white-out everything, so I set up an approach to the east end of the 1,700-foot strip, which had no obstructions. There was a river at the other end. Everything was going just fine until after touching down just beyond the first two lanterns, turning on the landing lights, and hitting the brakes.

The tires just skidded on the packed snow, and the other runway-end lights were coming up real fast. A go-around as this point would have been much more dangerous than sliding into the river, so in desperation I jammed on the right rudder and brake, and the 206 did a semi-ground loop, throwing snow every which way as we skidded sideways to a stop, about 20 feet from the river’s edge.

After regaining my composure, I got out and looked back down the runway. A local saw my perplexed look and said, “Pretty short, huh?” I asked him if the other lanterns were at the end of the runway, and he said no. Those had blown out and the other two must be in about the middle (of an already short runway).

After unloading, the flight back to Kotzebue was uneventful, like all flights should be.

That flight, along with many others by now, are in a file somewhere in my brain labeled “experiences.” Every possible situation that Mr. Bad Luck throws at you can’t be predicted or prepared for, so be flexible, creative, and vigilant to defeat him the next time he tries to throw an unexpected problem at you.

Illustrations by Barry Ross