A Father Goes Flying With The Kid

By Wayne Pinger I dipped the fuel tanks with my home-calibrated doweling, a dipstick gas gauge I made and strategically notched at 9 and 18 gallons, or average one and…

The Kid’s instructional droning continued, and at one point I considered shutting down his headset. But he finally clammed

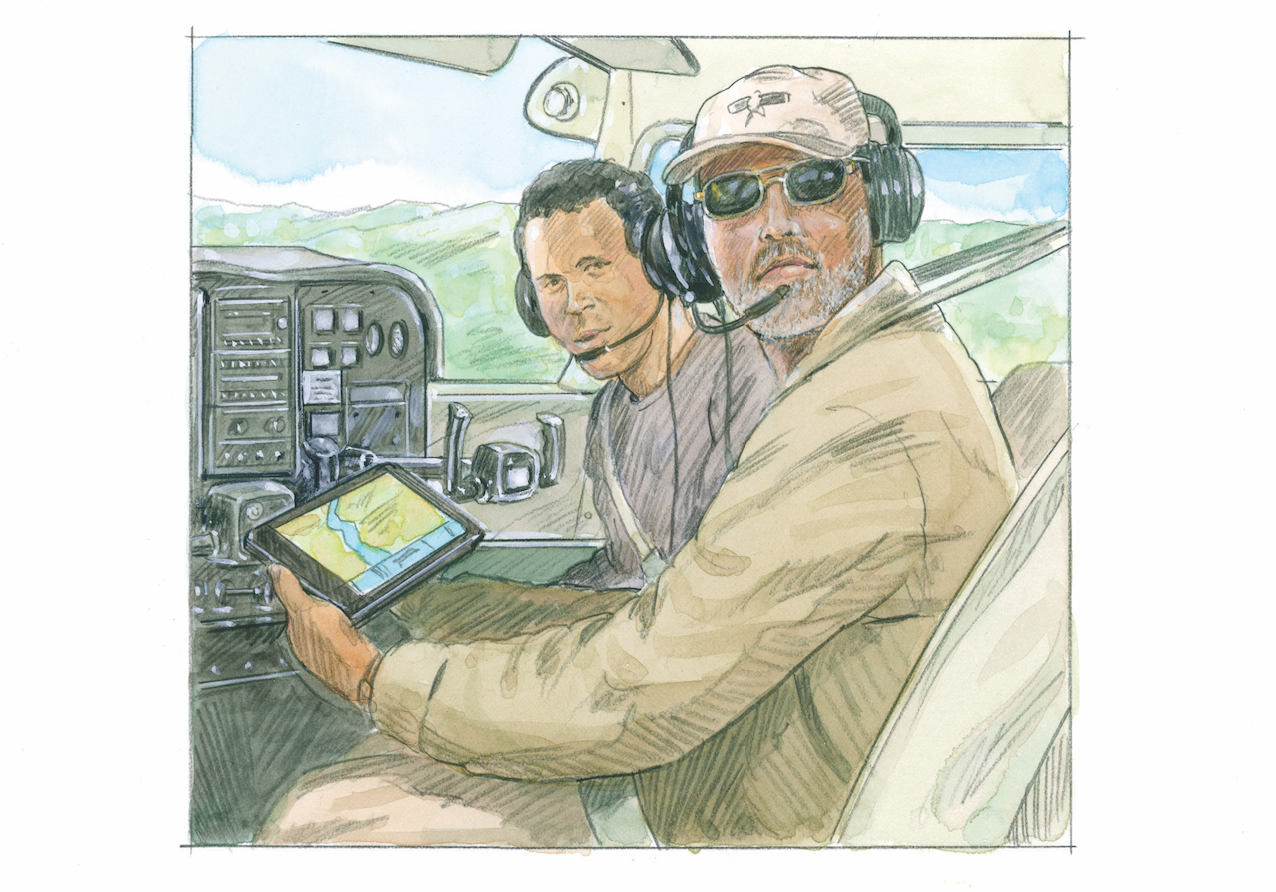

up. I had time to grab my iPad from the side pocket and with the help of ForeFlight (what a great navigation program) figured out where

we were. [Illustration by Barry Ross]

By Wayne Pinger

I dipped the fuel tanks with my home-calibrated doweling, a dipstick gas gauge I made and strategically notched at 9 and 18 gallons, or average one and two hours of flight. I cross-drilled it and glued a smaller dowel through to form a T to avoid dropping it in the tank. Still, the task of checking the fuel was far from easy as I balanced, one foot on the wing strut and the other on a not-very-robust step riveted to the fuselage. The “Kid” had offered to check the fuel, but I said, hanging on and trying to read my dipstick: “No, I can do it; how much was it?”

The Kid picks up the bill and reads it: “32 gallons,” and realizes he’s been had. Gas bill in hand and no other immediate task, he gives me the stink eye and walks to the FBO to pay.

Goodbye, Dolly

“Dolly” is one of the Kid’s airplanes but has been in my care for nearly eight years. I gave up solo flying a while back because of age-related forgetfulness, but with a competent pilot in the right-hand seat, I am ready to go. I still have my Basic Med, and I’m legal by about a month under my last flight review – “So, better enjoy it, Flyboy, because this might be it.”

Tomorrow, Dolly will fly the Kid to California to her new temporary home. An inspection will follow, and then she will go on the block for sale. Already, I am told, there is an interested buyer. I hope the lucky buyer will treat her well.

I kick the tires, check the oil, and walk around with my hand on the leading edges of the wings looking for damage but finding only one crusty bug carcass that I moisten and rub off. I imagine I feel a touch of goodbye from Dolly, a Cessna 172N.

She looked and seemed OK, so we get in, fumble with the seat belts, turn the master switch to “On,” fuel selector to “Both,” and I pump the primer knob twice.

“You only need to prime it once and make sure the primer is locked afterward,” says my know-it-all son in his “teacher-student” voice.

I smile but don’t respond. I have started this engine and ones like it once or twice before. Dolly comes alive with a friendly, familiar heartbeat of 700 rpm.

“This is not my first rodeo,” I say with a smile, knowing it’s been nearly four months since I last flew: “This is one rusty cowboy.”

Soon we are taxiing to the ramp while I’m admonished to raise the windward aileron (we have a 5-knot crosswind the Kid seems to think of as a small hurricane), and, “Taxi no faster than a person would walk.”Once again, I pretend not to hear his advice, a product of his many years of aviation experience and a grossly swelled head.

He does have several thousand hours in his logbook compared to my 500 or so, but he’s not a CFI, and unless I’m paying him, I don’t require his guidance. Finally I remind him of that fact. He is, of course, delighted.

After a good run-up, everything is green, and I announce: “Merlin traffic, white Skyhawk departing east on 13, Merlin traffic.”

“You really should identify with your tail number... and it’s ‘Grants Pass’ airport, not ‘Merlin.’ Other pilots flying in might be confused with that nomenclature,” and he really did say ‘nomenclature.’

When he was growing up, I taught him a lot. I demonstrated a straight arrow of morality and on a practical level, exposed him to a world of mechanical knowledge, starting him at age 10 with a Honda 50. He did well, and I graduated him to a Yamaha JT-1 Mini Enduro. When he was tall enough to see over the fender of most anything, I taught him about ignition and carburetion systems, and about motorcycles, riverboats, chainsaws, engine-driven compressors, generators, and anything else with a gas engine. The Kid learned a lot, but the word ‘nomenclature’ was not in the knowledge he gleaned from my fine tutelage.

En Route Attitudes

As we pass 400 feet, I reduce the rpm and trim for a 300 fpm climb. A right turn would put me in the pattern for 31, the usual runway, so I turn left and head for 4,000 feet. The Kid says nothing, so I assume there’s hidden approval in his silence. Things seem to be going well until I notice the airspeed indicator is near zero. The Kid seems not to notice, and I don’t call his attention to the blue pitot tube protector, the one his mom made, still protecting the pitot tube.

Some minutes later at 4,000, I lean the mixture, adjust the trim, and push the sun visor aside. We are headed west and skimming over the hills some folks call mountains. The air is dead calm under high broken cloud cover, and it’s 70 degrees.

In a few more minutes, when he is finally done futzing with some sort of navigation app on his phone and we are nicely on our way to Gold Beach, he puts it aside, adjusts his hat, and says in a commanding voice: “What’s the oil temperature and pressure?”

I pleasantly answer, hoping he still doesn’t notice the airspeed dial: “They’re in the green.” I scan the instruments occasionally, and just had.

I was pushing my Cessna 170 through the clouds and across the tundra when “His Majesty of the

Air” was still in grade school. The A&P and AI certificates he has are great, and I’m proud of him and my daughter-in-law having their own big-city flight service center, but those pieces of paper don’t make him my king.

I hold back my ire because I’m thinking about his high school graduation 45 years ago, when he was still pretending respect for his elders.

After graduation, the Kid signed up for A&P classes at the local community college. He worked

at East-Side Hardware in the mornings and attended classes in the afternoons. I remember when

he rebuilt the engine out of his first airplane, a Taylorcraft that was 80 percent fabric and 20 percent duct tape. His first complete and total rebuild was done on our kitchen table. He split the case over the propane stove in the kitchen because it was winter and nearly 35-below in the garage.

Low and Slow

The Kid’s instructional droning continued, and at one point I considered shutting down his headset. But he finally clammed up. I had time to grab my iPad from the side pocket and with the help of ForeFlight (what a great navigation program) figured out where we were.

We crossed a small set of hills and the untamed Rogue River appeared below us. With a slide-slip that would please Bob Hoover, we were at maybe 200 feet, doing lazy turns following the Rogue’s path to the ocean. We were low, enjoying the sights, seeing sandbars slipping by, and an occasional fisherman who would wave—some with an open hand and some with just the middle finger.

Smooth Landings

I grab my checklist and prepare for the landing at Gold Beach. I radio five or so miles up the river from the bridge, and without negative commentary from my passenger, Dolly slowly ascends to pattern altitude. A minute or so later, we are over the ocean in a lazy left turn, and then on a very extended downwind for landing on 34. I radio again as the mixture goes to full, and pull power to zero when crossing opposite the landing threshold.

It feels good turning base and I pray he doesn’t look at the airspeed. Well past the breakers and headed toward the hills behind Gold Beach, it’s a grand day. I’m a little high turning final and put in a smidge more flaps while pulling on the carb heat and flying slightly into a left-to- right crosswind. The Kid says, “You don’t need carb heat, the carburetor is warm, it’s bolted firm on the oil pan...it might stutter if you have to go around.”

I counter his directive in a voice reminiscent of a personal hero, Henry Kissinger: “I always land using carb heat, and I only pepper my steaks.”

“You’re the pilot,” says the Kid, rolling his eyes. I wondered if he might be inspecting his brain cells.

He is hardly relaxed as Dolly lines up while slipping into the crosswind and touches down gently: first the left main and, a split second later, the right main and nosewheel.

Though I never really learned to land a nosewheel airplane well, the gods of flight smiled on me as Dolly and I made the smoothest 10-knot crosswind landing ever—with no accolade from the Kid, of course.

I taxied close to a porta-potty, keeping the up-wind aileron in its proper position.

When I returned from the facilities, the Kid was checking the oil and cleaning the windshield—the pitot-tube cover hanging from his back pocket. He never said a word.

After lunch, we flew north along the coast to Cape Blanco for a touch- and-go, then on to Bandon, and after Southwest Oregon Regional airport in Coos Bay, I turned toward the Grants Pass Airport in Merlin.

About 10 miles out, I checked the AWOS and radioed: “Grants Pass traffic, Cessna 555-Mike-Kilo, 10 west at 25-hundred inbound, landing 31: Grants Pass traffic.” And the Kid nodded with his approval that at the time seemed quite important.

Editor's Note: This story originally appeared in the July 2023 issue of Plane & Pilot.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox