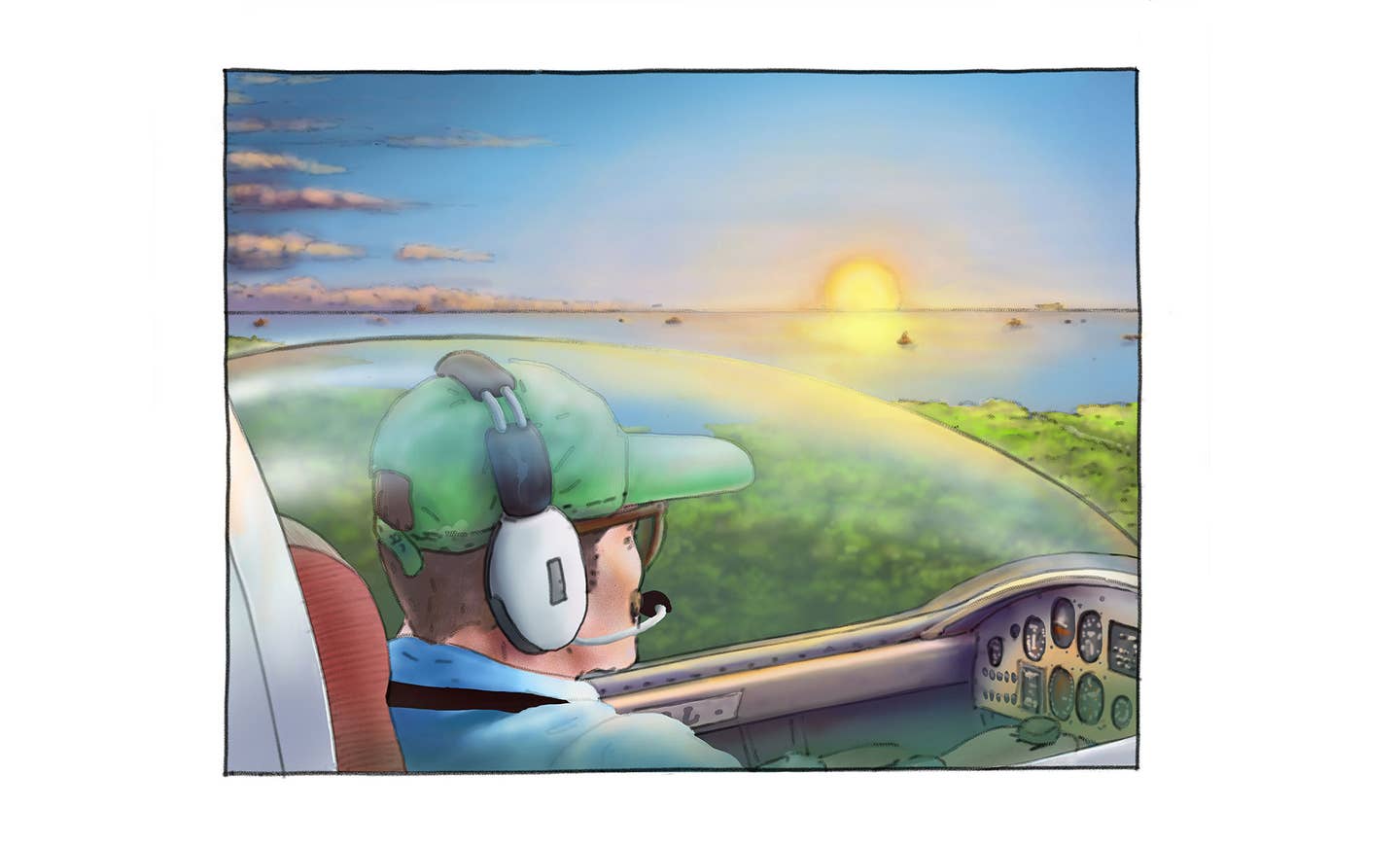

Settling In For The Long Haul

Long-distance cruise is the Skylane’s forte; with 79 usable gallons and burning 12 gph at 65% power, it can cover 500 to 700 miles in still air. Skylanes like to…

Long-distance cruise is the Skylane's forte; with 79 usable gallons and burning 12 gph at 65% power, it can cover 500 to 700 miles in still air. Skylanes like to be flown at 7,000 feet or so, picking up an extra 6 to 10 knots over lower altitudes. Forgetting to close the cowl flaps at top-of-climb will cost 5 knots of speed. I like to pull the prop back to 2,300 rpm in the early Skylanes, and with the O-470-U, I'll cruise at 2,200 rpm. I find that a Skylane will tend to "hunt" up and down 100 feet or so during cruise, even in smooth air; just expect it and ignore it. The carbureted O-470 engine has notoriously poor mixture distribution, so don't waste your money and time on a six-cylinder EGT for cruise control. Just tune your single-probe EGT to 100 degrees rich of peak or smooth operation.

With its heavier controls, a Skylane is not an airplane you'd choose for throwing around in training maneuvers. However, if you want to practice slow flight, stalls and steep turns, you'll find it doesn't have a mean bone in its body. The indicated airspeed will drop off the scale before the nose finally breaks in a stall shudder, recovering promptly. Otherwise, just keep it trimmed appropriately and use it as designed.

Starting down, 15 to 17 inches of manifold pressure can generate a comfortable rate of descent or, if the air's smooth, you can knock a couple of inches off the cruise power setting and let the airspeed build up, adding some left rudder trim. If you're new to the game, don't forget to take off an inch of MP every thousand feet as you descend.

If you leave the power at its descent setting as you enter the traffic pattern, the Skylane will fit right into the trainer traffic; most 182s have a 140-knot callout for the first 10 degrees of flaps, with 95 knots the limit for further extension. Retain 10 to 12 inches of manifold pressure as you enter the approach glide, adding half-flap and slowing to 80 knots for base leg. Then use full flaps and 70 knots on final.

Unlike a Skyhawk, the Skylane should be landed with 40 degrees of flap because it needs the drag for stopping. Don't carry extra speed into the landing; 65 knots across the fence is plenty, and be prepared to get the yoke way back into your lap for the touchdown at 50-55 knots. You don't want to let the nosewheel touch until the mains are solidly down. Avoid bringing the throttle to idle until you're about ready to flare out of the glide; a Skylane is heavy and will develop a high rate of sink out there on final with power off, causing a hard landing if you're not careful.

As we said at the beginning, Skylanes are great all-around performers. That's the reason everyone is trying to find a good used one.

Read more about used Cessna 182 Skylanes here.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox