Best Personal Locator Beacons And Satellite Communicators for 2021

We look into how PLBs work, the differences between them, and which one, or ones, to buy.

In a Plane & Pilot story published late last year, we focused on the tragic disappearance of a Cessna 310 in Alaska in 1972. The chartered light twin went down somewhere between Anchorage and Juneau while carrying two United States Congressmen. After nearly 50 years, the location of the plane remains a mystery. If it's ever found, it would be national front page news, but for now, there's little risk of that happening, sadly.

While the occupants are long gone by now, it might have been a grisly end. One horrifying scenario is that the plane made a survivable forced landing but that the four occupants weren't able to make their way back to safety.

Back in the early 1970s, locating downed planes was largely done the old-fashioned way---that is, looking for them with human eyeballs by air, land or sea. It's not a very effective method; it's really hard to spot a crashed plane or any sign of it. When searchers don't even have a good starting point, the odds of finding missing aircraft are slim. In a wild and remote place like Alaska, they're even slimmer.

Of course, nobody really wants to think about what happens after a crash or a forced landing, but we really should. According to recent NTSB data, less than 20% of general aviation accidents result in fatalities. The great majority of people survive the crash. That's still hundreds of people every year who find themselves, possibly with broken bones or worse, in a disabled airplane.

If you land gear-up at a busy airport during primetime, it might be embarrassing, but your whereabouts won't be a mystery (though at that moment you might wish that they were). But what if you're not so lucky? What if you go down somewhere remote with no means of alerting first responders? If you're far from help, hemmed in by inaccessible terrain or perhaps too injured to seek help or even make shelter, the prospects might be grim.

Enter ELTs

In 1973, after the disappearance of the flight carrying the two Congressmen and two others, the FAA began requiring the installation of Emergency Locator Transmitters (ELTs) in almost all aircraft. Ironically, Alaska had already begun requiring ELTs---it also allowed portable ones---but the pilot apparently forgot to take his along for the flight. Whether it would have worked or not is anyone's guess. If the occupants had survived, the search that was launched immediately after the plane failed to show up in Juneau might have been able to find that ELT signal and home in on it. Even if the occupants were killed in the presumed crash, at least their families would have had the peace of mind of knowing what happened.

ELTs, which are designed to automatically activate in the event of a crash and send out a signal to would-be rescuers, are notoriously unsuccessful at doing that, though they're great at going off when you're at dinner and your airplane is sitting on the ramp. Nuisance alerts with traditional ELTs are beyond common.

In addition to the now-standard 406 MHz emergency band, all Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs) have a low-power beacon that transmits on 121.5 MHz, the same frequency band used by older-model ELTs. While the 121.5 MHz signal works well for PLBs---the 406 MHz signal gets rescuers to the right area, and the 121.5 MHz beacon helps them home in on the source of the signal---it hasn't proven to be an effective method for locating downed aircraft by itself. According to NOAA-SARSAT data, 121.5 MHz ELTs have a 97% false alarm rate and only activate properly in about 12% of airplane crashes. Not good odds for getting help.

For the past several years, satellites have put old-fashioned ELTs and their 121.5 MHz chatter on permanent ignore mode, so even if the beacon does go off after a crash, you have to hope there's someone nearby to hear it and get the ball rolling. A 406 MHz beacon gets that job done much more reliably.

Newer ELTs are here, and they are better in every way, operating on 406 MHz, which provides global coverage, unlike 121.5 MHz ELTs, which need an aircraft or station in signal range to pick up an emergency alert. There's also no way to personalize a 121.5 MHz signal, while the 406 MHz ELTs and PLBs are registered to their owners, allowing emergency responders nearly immediate access to information about who they're looking for. Time for responders to reach an accident site is reduced by an average of six hours with 406 MHz ELTs.

They're also better at activating when they should and not activating when they shouldn't broadcast a satellite signal on 406 MHz, calls to which are monitored 24/7/365. While most planes still need to have a working ELT, owners have the option of swapping out their old 121.5 models for one of the improved boxes. Costs are typically between $500 and $1,500, plus installation.

Cell Phones? ADS-B? Flight Plans? Yes, Yes And Yes!

You might have heard of the recent report by the Civil Air Patrol that it had successfully used a combination of cell phone tracking ADS-B/radar to quickly locate downed planes (dozens of them, in fact). Its message wasn't that ELTs don't work, though it's hard to avoid that conclusion. But relying on a cell phone is dicey. You need to make sure that it's charged and accessible (normally not a problem) and that people know where you were headed and at what time---so a flight plan makes great sense. Under IFR, you're automatically on a flight plan, and ATC knows precisely where you are at all times (or at least close to it). And if you were forced down, it's quite possible that you would have no reception, which means you'd have no means of contacting anyone, and it might mean that your location is a mystery as well. So the bottom line is, cell phones are great, but they're limited in what they can do and how reliably they can do it.

ELTs and PLBs?

Even if your plane is outfitted with an outmoded but still-required 121.5 unit, which it very likely is, you don't need to hitch your rescue wagon to that stone-age technology. You can leave the old unit where it is and supplement it with a personal unit, either a dedicated Personal Locator Beacon or a satellite communicator. You can also upgrade that old unit with a new one that transmits on the always-monitored 406 MHz satellite link channel.

PLBs were approved for use in the U.S. in 2003. Even if you can't get cell phone reception, a PLB signal will get through and, these days, track your location to within about 100 meters---usually in just a few minutes.

PLBs transmit a personalized signal at 406 MHz, an international distress frequency that can be received by the COSPAS-SARSAT satellite constellation. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) monitors the system in the U.S., including PLB registration. That registration is good for two years and is required by law. One of the benefits of registration is that any distress signal will identify the owner, with personal info, to search-and-rescue personnel.

These devices fall into two general categories---basic PLBs and satellite messengers. PLBs only act as beacons. They're extremely simple to operate and typically have no other functions. There's a lot to be said for this approach, too. A PLB is a dedicated unit with a design intended to do one thing and do it well. For pilots who often fly over remote areas, a PLB can be and has been a lifesaver.

Satellite messengers are great, too, but in a very different way. They come with a range of capabilities that often include GPS functions and text communications, along with custom apps for linking to your phone or tablet.

Which device is right for you? If you're simply looking for a solid backup for an ELT---something anyone with an older-generation ELT should think about given their less-than-reliable track record---a basic PLB is probably the best way to go. Little maintenance is required, and the price for most models is reasonable. Given the similarity in cost, deciding between basic PLB models is largely a matter of picking which features and operating styles you prefer, such as waterproofing and protection against accidentally sending out a distress signal while testing the unit.

For pilots planning more extensive backwoods travel or flying over sparsely populated terrain, satellite messenger functions can offer a lot of safety options geared specifically for trips away from cell phone reception.

In terms of budget, a good rule of thumb for these is that more features equal greater expense. Even for units with similar initial costs, most satellite messengers also require ongoing subscription plans, which is worth paying attention to as the price for plans can vary significantly.

With all of that in mind, here are some of the options currently available. Some are true PLBs, others are satellite communicators with non-406MHz emergency links, and others are interesting combinations of these and other features.

ACR ResQLink PLBs

ACR offers a number of personal devices, some of which combine PLB and 121.5 capabilities. The ResQLink 400, which sells for $309, has no subscription cost and features built-in GPS and Galileo satellite receivers. It's buoyant, has an integrated strobe and infrared strobe, and its battery can last up to five years. For an additional $50, the ResQLink View model features a display.

The company's ARTEX PLB is a very basic model that still does the PLB job nicely. For $289.95 and no subscription price, it's a great deal, and to top it off, it easily fits in your pocket. It's marketed under a number of brand and product names, but the unit's basic design and function remain the same. Learn more at acrartex.com/products/resqlink-plb.

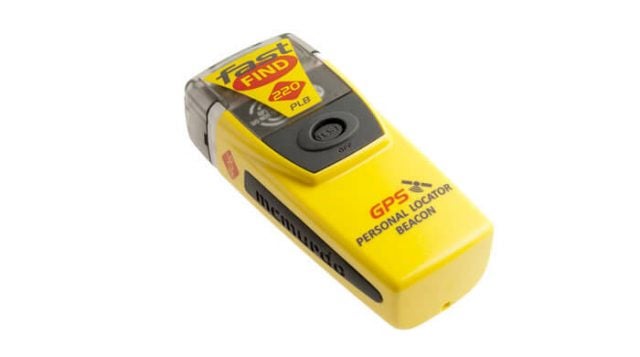

McMurdo FastFind 220A

The FastFind 220A from McMurdo is an upgraded go-anywhere PLB. It can transmit continually for a minimum of 24 hours on both 406 and 121.5 MHz. The unit doesn't come with too many frills, but it is waterproof to 10 meters and comes with a floatation pouch and lanyard, which might help you keep track of it when you need it close. It also has an LED strobe that will flash S.O.S. in Morse code when activated. When the PLB is turned on, the indicator light will begin to flash. The pattern and number of flashes show the progress of the emergency signal---two flashes per second when the unit is activated and looking for a GPS fix, three per second when a GPS fix has been acquired, and one long followed by three short flashes in 50 seconds when the distress signal and GPS position have been transmitted.

The FastFind 220A costs $250. Learn more at oroliamaritime.com/products/mcmurdo-fastfind-220.

SPOT Gen4

The SPOT Gen4 is a Globalstar-based satellite locator and messenger that straddles the line between satellite messenger and basic PLB. It doesn't provide any kind of two-way messaging, but it can be used to send either an S.O.S. alert to the emergency network, a standardized all-okay check-in or a help message to personal contacts. It can also send preset text messages. Lastly, there's a help button that will alert personal contacts that you need assistance in a non-emergency situation. Messages and personal contacts are set by logging into your online account, so they can't be changed without internet access. Each type of message has its own button.

The SPOT Gen4 also has a tracking function that shares your GPS location to your online account at selected intervals. The unit is dustproof and waterproof. It can stay functional after being submerged (1 meter) for up to 30 minutes. It runs on 4 AAA batteries, which are good for 1,250 messages. Like the other satellite messengers, SPOT requires a subscription to function. Plans start at $11.95 per month (with a one-year contract and $19.95 activation fee) for unlimited S.O.S. and help messages and basic tracking. The SPOT Gen4 goes for $149.99. Learn more at findmespot.com/en-us/products-services/spot-gen4.

Garmin inReach Communicators Plus

Garmin's lineup of personal handheld communicators runs a short gamut from its inReach Mini ($349.99) to its inReach Explorer+ ($449.99). The latter goes a lot further than just providing a location in an emergency. It offers two-way text messaging via satellite, so it's available in areas without cell service (100% global coverage through the Iridium satellite network). Once an S.O.S. is triggered by the user, the unit can be used to text-message directly with the GEOS 24/7 search-and-rescue monitoring center throughout the emergency.

In addition, the Explorer+ is a basic multifunction navigator. It has a digital compass, a baro altimeter and an accelerometer. It can also be paired with the iOS and Android free mobile Earthmate apps, which provide access to topographic maps and NOAA charts.

The Explorer+'s rechargeable lithium battery can last up to 100 hours in tracking mode. If the unit is in power-save mode, battery life can stretch to 30 days. The Explorer+ is 6.5 inches long and weighs in at 7.5 ounces. It's impact- and water-resistant. Other features include non-emergency location tracking and sharing, access to weather forecasts and GPS guidance.

Cost for the unit is $449.99. An active satellite subscription is required to use it---and that includes the S.O.S. and emergency features. Monthly subscription plans range from $11.95 to $99.95. Learn more at buy.garmin.com/en-US/US/p/561269.

Iridium GO

For even more functionality than the standard satellite messengers, there's the Iridium GO mobile Wi-Fi hotspot that provides internet, including internet telephony, via satellite. Its subscription plans are expensive, but the capability is hard to match.

Not a PLB, Iridium GO enables your smartphone to call and text message from just about anywhere in the world via the Iridium satellite network. It's compatible with both Apple and Android products.

The Iridium GO unit works with associated apps for a variety of mobile devices. For emergencies, the unit has an S.O.S. button. Users need to configure the S.O.S.---via the Iridium GO app---prior to use. It can be programmed both to send the GPS location and emergency alert to a preset phone number or to GEOS worldwide search and rescue. An active subscription is required for GEOS service. A working mobile device isn't needed to activate the S.O.S. function.

One Iridium GO unit can support up to five mobile devices operating within a 100-foot radius. While it offers the most communications options in an emergency, there are some drawbacks. The rechargeable battery lasts just 15.5 hours when it's on standby and provides 5.5 hours' talk time. Purchase price for the Iridium GO with the aviation kit is $995.00. Subscription plans range from $59 per month for 40 hours of connectivity to $149.99 per month for unlimited data and text. Learn more at iridium.com/products/iridium-go. PP

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox