Pro Tips For Private Pilots: What Is Your “Bingo Fuel?”

How professionals establish personal fuel minimums to avoid running out of gas.

Photo courtesy of Robbie McConnel/Instagram

The No. 1 cause of general aviation aircraft landing on highways and farm fields, rather than the intended airport, is fuel mismanagement and exhaustion. When done well, this off-airport landing is often followed by the obligatory interview on the local news at 10, explaining why you landed on that highway just a wee bit short of the local airport! On the other hand, military and professional pilots, who often have significantly lower fuel-endurance margins to work with, have a much better record. We rarely, if ever, hear of a jet aircraft running out of fuel inflight. How do they do this? One answer is the military concept of "bingo fuel," or personal fuel minimums.

Simply put, military jet pilots calculate a fuel at which they will return to base for every flight. Consider a flight of four beautiful T-38 Talon Jet Trainers flying in a four-ship formation. Each of the amazing little machines has an endurance of less than 1.8 hours. In comparison to our general aviation aircraft, these pilots appear to be low on fuel before they even take off. However, before they depart, each pilot computes a "bingo fuel" (the minimum fuel required to leave their practice area and return to base), and, most importantly, they stick to it.

When the formation leader asks the flight of four jets to check their fuel status, it sounds something like this: "Eagle flight, fuel check!Eagle Two okay, Eagle Three okay, Eagle Four bingo fuel...Roger, Eagle Flight, let's RTB [return to base]." And that's it. When the first jet in the formation gets to bingo fuel, the entire formation goes home. No discussion, no rationalizing, no pleading, "Can we do just one more loop, please, please?" Just to be clear, the airlines have a similar and just as effective fuel discipline system, but they just don't have as cool a name for it.

So how do we compute a bingo fuel for our mighty general aviation steeds?

Step One:

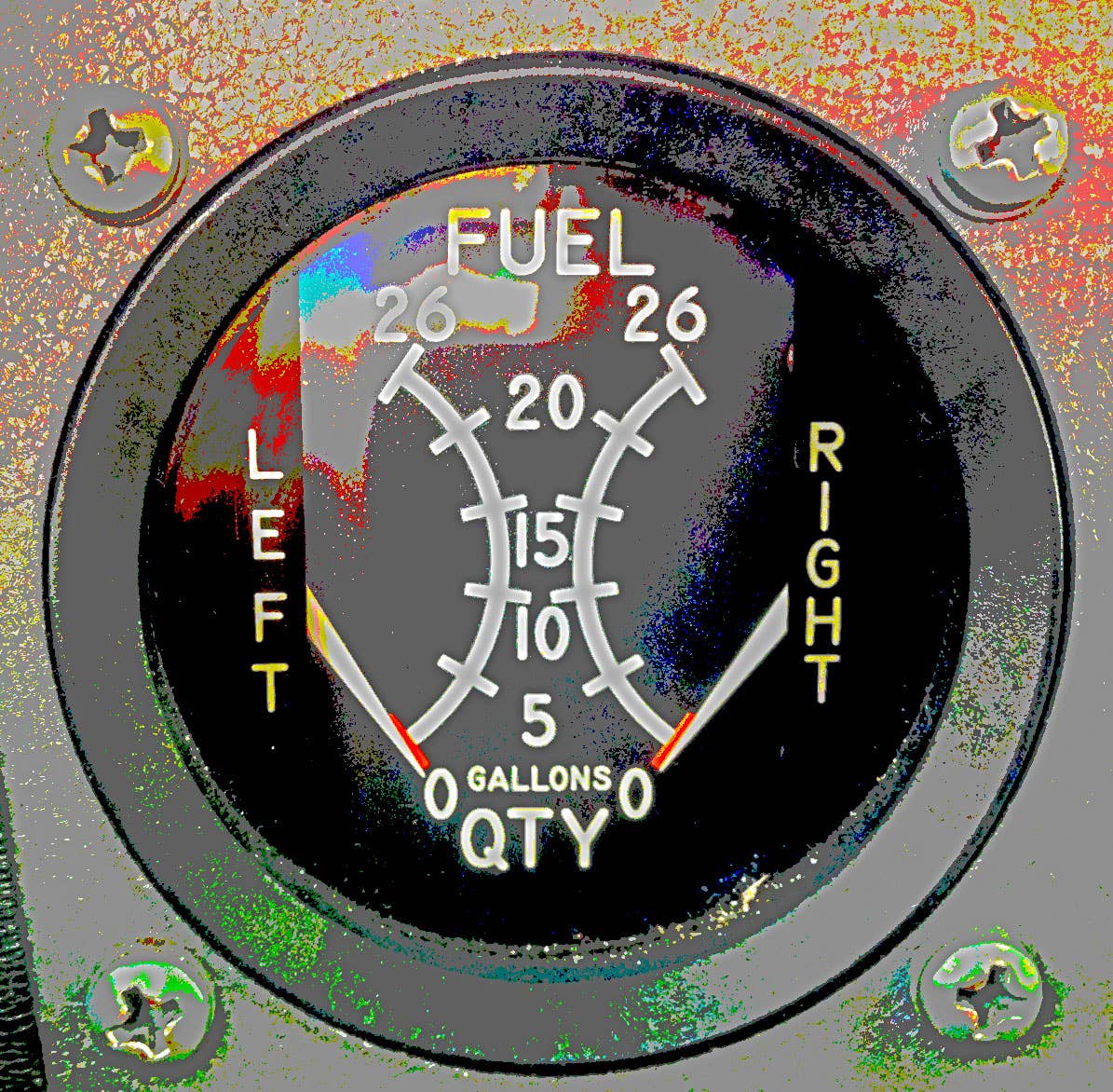

Determine the accuracy of your fuel gauge system. The average 35-year-old GA aircraft has float-type fuel gauges designed in the 1950s. They are accurate in level flight but less so in climbs, descents and maneuvers. These gauges should be considered but one of several ways to measure fuel remaining. The second method is the clock. Fuel burn over time, assuming we know our fuel burn rate, is the second, and often most accurate, vote. And, finally, more recent GA aircraft have very accurate fuel flow/quantity systems. Always compare all these methods to determine the actual fuel on board.

Step Two:

Determine your actual fuel flow. The book figures for most aircraft consider leaning the mixture as appropriate for altitude. However, pilots based in the Mile High City of Denver, Colorado, lean the mixture for taxi, takeoff, climb out, cruise, descent, approach, landing and taxi back into the ramp. Sea-level pilots in Florida may be less inclined to touch the dreaded red mixture knob except for cruise, and even then, sparingly. Either way works, but each produces a different specific fuel consumption. Make sure you know yours.

Step Three:

Convert fuel use into specific fuel and time targets that you will adhere to!period. The FAR required minimum of 30 minutes for VFR and 45 minutes IFR are just that---minimums. In the average 35-year-old Cessna 172, 30 minutes boils down to 2.5 gallons of fuel per wing tank, 5 gallons total. Forty-five minutes is little better at 3.5 gallons per tank. Imagine approaching your destination with just 5 gallons total fuel on board, and another pilot lands gear-up and closes the one and only runway. You must act fast before it gets really quiet in your airplane. So maybe your personal "bingo fuel" should be a bit higher. Let's look at one pilot's approach to establishing a personal minimum fuel.

- THE AIRCRAFT: A legacy Cessna 172 with 50-year-old fuel gauge technology and no fuel flow meter. Fifty gallons useable fuel on board.

- THE PILOT: Leans aggressively and reduces power in strong tailwinds to improve fuel mileage.

- THE RESEARCH: The pilot observes 9 to 10 gallons per hour and has dipped the tanks after flight to confirm the accuracy level of the fuel gauges at low quantities.

- THE DECISION: Regardless of the FAR minimums, this pilot has decided to be safely on the ground with a minimum of one hour of fuel remaining on every flight!no exceptions.

So, this pilot decides their personal "Bingo Fuel" occurs under either of the following two conditions. First, anytime the aircraft has been airborne for three hours and 30 minutes and has not yet started the descent from cruise altitude for landing. This includes an allowance for a balked approach and a second approach and landing. Second, anytime it appears that the aircraft will still be airborne with less than 5 gallons indicated in either of the fuel gauges, or 10 gallons total. In each case, the pilot will proceed to land immediately. Your computations will likely be different, but once arrived at, stick with them.

"This concept only works if you figure out your personal fuel minimums and then stick to them. No rationalizing that the gauges are reading low, no hoping you can eke out a few more miles, and no trying to squeeze in one more pattern."

A couple final thoughts. This concept only works if you figure out your personal fuel minimums and then stick to them. No rationalizing that the gauges are reading low, no hoping you can eke out a few more miles, and no trying to squeeze in one more pattern. Second, the term "bingo fuel" is simply a way to understand your personal fuel minimums. It is not recognized by the pilot controller glossary as the terms "minimum fuel" and "emergency fuel" are. So please do not use it on the radio to air traffic control.

Much better to make an en-route stop for extra gas and have to explain to your waiting relatives why you are a bit late than to have to give all those pesky TV interviews at the side of an interstate highway, explaining how you made that amazing, and embarrassing, "dead stick" landing. Fly safe! PP

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox