A Pilot Takes An Engine Course

Ever wonder if you really know enough about your engine? Our guy did, too. He didn’t hit YouTube. He went to college.

Like most pilots, I periodically examine aircraft-for-sale ads in various publications, like Trade-A-Plane. These ads are always good for a fantasy flight as I imagine traveling to Oklahoma, Florida or even Alaska to acquire an aircraft that comes with "10 hours since MOH," "fresh TOH" or some similar inducement. However, over the years, I have come to realize that I wasn't sure exactly how "Major Overhaul" and "Top Overhaul" compare with "factory remanufactured" or "factory overhaul" and other descriptions. I knew my fantasy purchase would come with a trusted preflight inspection from an A&P. But as a resident of the Central Coast of California, who could I trust to do an inspection in another state?

That question led to another: How could I become knowledgeable enough to make my own assessment? The answer that came to me was to become an Airframe and Powerplane mechanic, or A&P. If I did, then could I not only do my own assessment, but I could perform a lot of the maintenance on my fantasy aircraft. This sort of thinking sat in the back of my mind a few years ago until I actually started to investigate where I might be able to work on an A&P.

I ran across the Gavilan Junior College A&P program at an informational booth at a local airshow. California's junior college programs offer students low-cost vocational training or academic training covering the first two years of college. Students can earn either an associate degree or vocational certification or transfer to four-year colleges and universities.

Gavilan College is the nearest junior college to me with an A&P program. Its main campus is in Gilroy, and its aviation maintenance program is at the San Martin Airport, a few miles north of the main campus. After attending a pilots' meeting at their facility and securing my family's support, I began juggling my work schedule to begin classes in the fall semester.

The Gavilan aviation maintenance A&P program has three basic components that align with the FAA's requirements in the General, Airframe and Powerplant categories. Certificates of completion are issued for each of these areas that allow the student to ultimately become a licensed A&P. Students normally take General and Airframe during the first year and Powerplant the second year. All of the programs combine formal study and hands-on shop learning on a daily basis.

At the end of the first year, a student can take the FAA General and Airframe written and practical exams and begin working as a certificated Airframe mechanic. The reality of the job market, however, is that the complete A&P is required for most maintenance jobs. The time demands of all courses are precisely recorded daily on electronic and physical time clocks to ensure FAA training requirements are met.

In the first-year General course, I learned to safety-wire, identify and order parts properly, research the AD package for an aircraft, and basic electrical skills. The shop work focused on simple hand-tool tasks, such as cutting threads, tube flaring, precision measurements and other skills that, for me, were either pretty rusty, or I had never seen before.

This past year, I took Powerplant in the fall semester because it accommodated my work schedule. Having now completed the first semester of Powerplant, which covers reciprocating engines, I really feel a sense of accomplishment. The second semester of Powerplant covers turbine engines. The classroom phase covers the fundamentals of reciprocating engine cycles, fuels, lubrication, cooling, spark generation, generators and alternators---all the things that are needed for an engine to run properly.

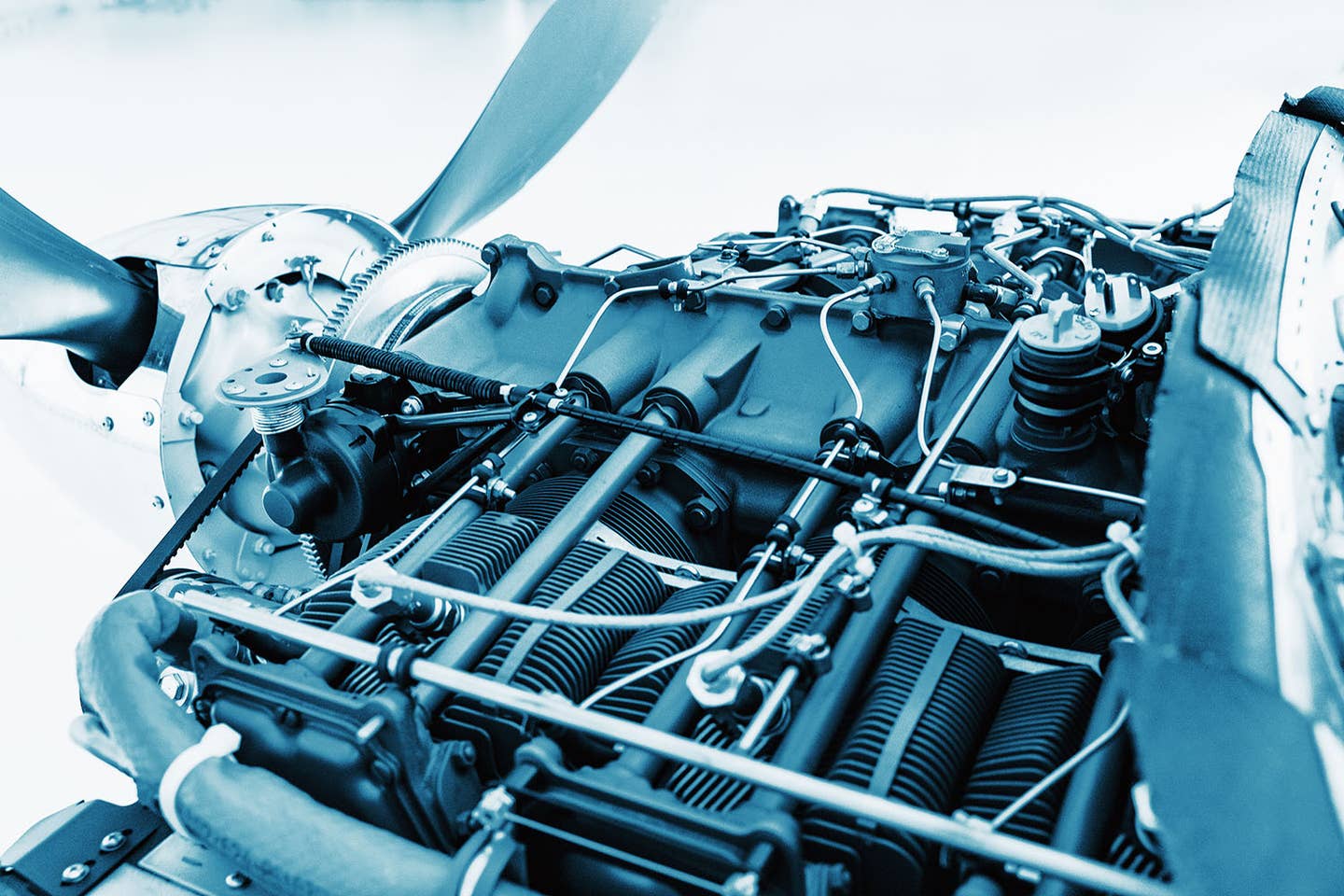

However, it was the lab work that was quite dramatic and what I really came for. In the accompanying photograph is the Lycoming O-320-D2A engine that was completely mine to tear down, measure, reassemble and get into running status. This project took about six weeks and was followed by teardowns and reassembly of starters, magnetos, generators, alternators, and float and pressure carburetors.

The learning curve was fast and steep, but our instructor's continuous guidance and hands-on help made it work. All students completely disassembled their own engines. Figure 2 shows my engine with the case split. Inspection according to the Lycoming engine repair manual showed several parts were out of dimensional tolerance. Since these were unairworthy exercise engines, students researched various parts catalogs to determine the appropriate replacement parts that would be needed if restoring airworthiness were the goal. In addition, students determined AD compliance for their engines.

After reassembly, with fortunately no parts left over, I mounted my engine on a test stand. Next, I added spark plugs that I had cleaned and gap checked, bolted on a test prop, timed the magnetos, added oil, and moved the stand to a location where the engine could be safely test run. It actually started as well as similar Lycoming engines I've used in rental 172s.

Further short test runs were made to check magneto drops, engine fluids and more. Rolling the test stand back to the hangar was immensely gratifying. This may all sound easy, but not everything went smoothly. On my first remating of the case, I left out one bearing half, necessitating re-splitting the case and going through the remating again. Surprisingly significant amounts of brute force were needed to accomplish some of the reassembly efforts on the cylinders. This was all part of the learning. I was continually afraid to exert a lot of force in tasks I hadn't tried before. This probably results from a lifelong tendency to overtorque, overtighten and break things. It became an area where the instructor's guidance was invaluable.

In two years, students become aviation professionals under the guidance of Department Chair Herb Spenner, who instructs the General and Airframe courses, and Powerplant instructor Paul Agaliotis. Both are long-term A&Ps and previous graduates of the Gavilan program. Spenner completed his A&P after significant management positions as an electrical engineer, so he brings an added dimension to electrical work. In addition, Spenner serves as an FAA-Designated Examiner. Agaliotis' prior career at a major air carrier also adds significantly to the real-world knowledge he brings to the students.

With the current hot job market for A&Ps, there have been recurrent visits to the school by major carriers, helicopter operators and the business aircraft market, which offer great opportunities to the Gavilan graduates for well-paying jobs with good futures. Although Gavilan and other programs make continual outreach efforts, it has proven a challenge to convince high school counselors to help students think outside the typical college track.

So, now I know a lot about what's under the cowling. More importantly, I've gained skills that will make me a better pilot and a much more knowledgeable communicator to maintenance personnel in the future. Whether I can complete the A&P at an extended pace is an open issue, but I am very glad to have come so far with the aid of Gavilan, Spenner and Agaliotis.

If you're interested in exploring A&P training programs, you can check with your local FSDO, or simply use Google to research what's available. Like Gavilan, most programs will probably be more than willing to show you their facilities and explain your options.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox