This Incredible Pilot: Katherine Stinson

When we think of pioneer women aviators, there are a few names that stand out: Jacqueline “Jackie” Cochran, Bessie Coleman, and Amelia Earhart among them. Each owns a unique story…

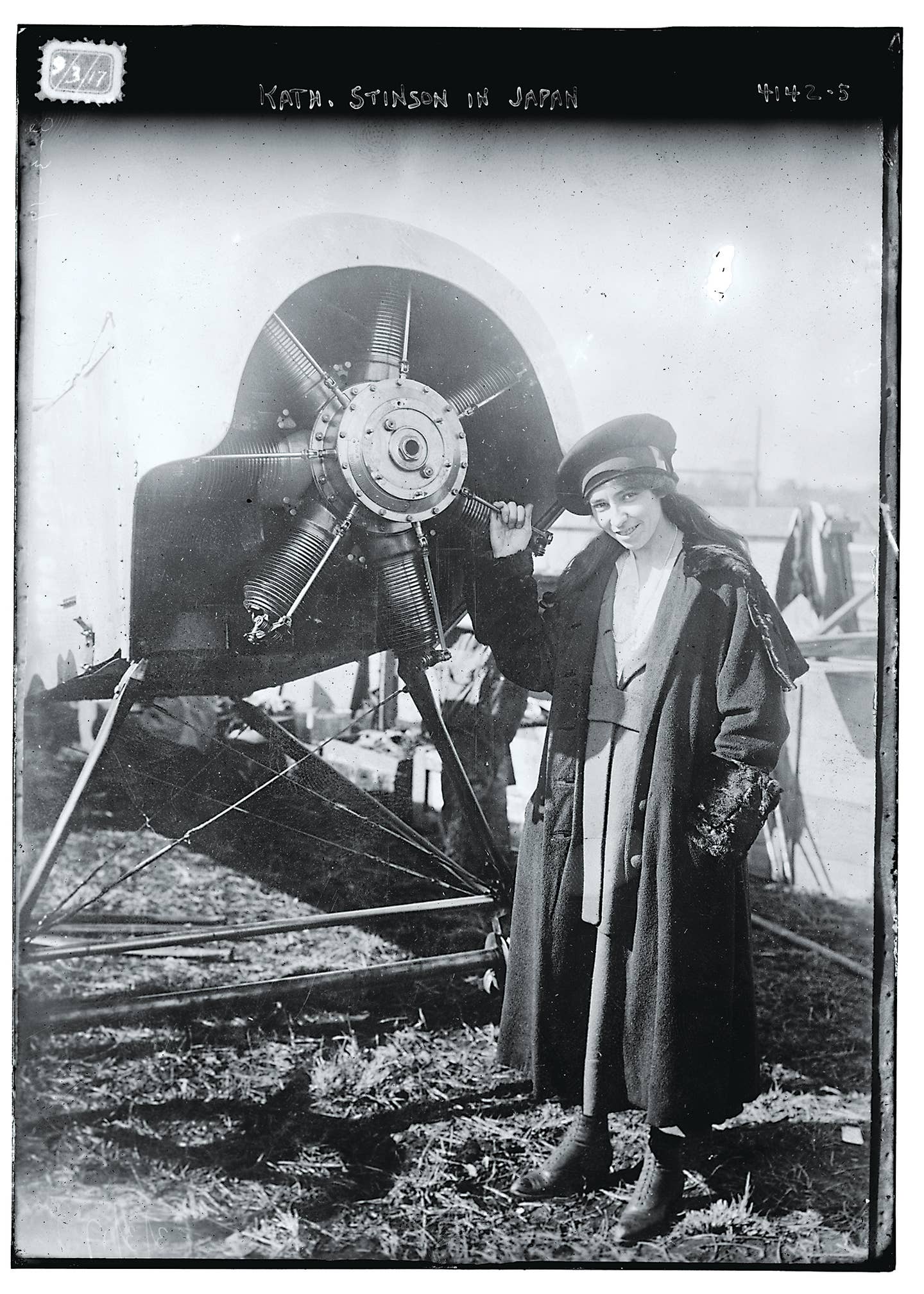

Stinson became the first female U.S. Postal Service pilot, but it was short-lived. [Library of Congress]

When we think of pioneer women aviators, there are a few names that stand out: Jacqueline

“Jackie” Cochran, Bessie Coleman, and Amelia Earhart among them. Each owns a unique story and particular accomplishments for which they areremembered. Others who set records in their time seemed to fade a little into the background of history. One of these pilots is Katherine Stinson.

Stinson, a contemporary of Earhart and the fourth U.S. woman to earn a pilot certificate, established a fair number of records in her day. She invented skywriting by attaching flares to her airplane and writing “CAL” in the California sky in 1915 and made public appearances around the world promoting aviation.

While her aerobatic firsts and endurance records are worthy of respect, some of her “quieter” contributions also continue to influence aviators and aviation today.

Most of us are likely familiar with Stinson airplanes but may not know that Katherine and her mother,

Emma, founded Stinson Aviation Co. in Arkansas in 1913, a precur- sor, at least in name, to her brother Eddie’s Stinson Aircraft Co. She and her mother also founded the Stinson Municipal Airport (KSSF) in San Antonio in 1915 and established a flying school where Katherine’s sister, Marjorie, was a flight instructor.

When civilian pilots were grounded a few years later as the country redi- rected its efforts to World War I, Katherine became the first female U.S. Postal Service pilot, but it was a short-lived occupation after the press erroneously reported she had bested her instructor in a “race” during her training missions.

In 1918, after the Army turned down the Stinson sisters when they tried to volunteer for military service, the “nineteen-year-old girl aviator”— she would have been 26 or 27 but was known for being petite—“...flying in a Curtill [sic] Military Tractor... picked up the contributions to the Red Cross, $100,000,000, at Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Albany, New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore, car- rying the checks to Secretary (William G.) McAdoo who received her person- ally on the steps of the United States Treasury in Washington,” according to a photo caption from the American Red Cross archives.

Assuming the caption recorded the right number of zeros (other sources report the total as $2 million), Stinson collected and transported the equiva- lent of $2 billion (or $40 million) in 2023 dollars to McAdoo in her Curtiss for the war effort.

She then went to Europe to serve as an ambulance driver, but a bout of tuberculosis cut her career short.

It was not until 17 years after Stinson’s death in 1977 that the Air Force’s Jeannie Flynn became the first female U.S. fighter pilot—poignant as Stinson had been denied joining the ranks of military aviators so many years before.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox