Pilot Stalls Plane on Short Final, Leads to Fatal Crash

What kind of problems do you try to resolve while airborne?

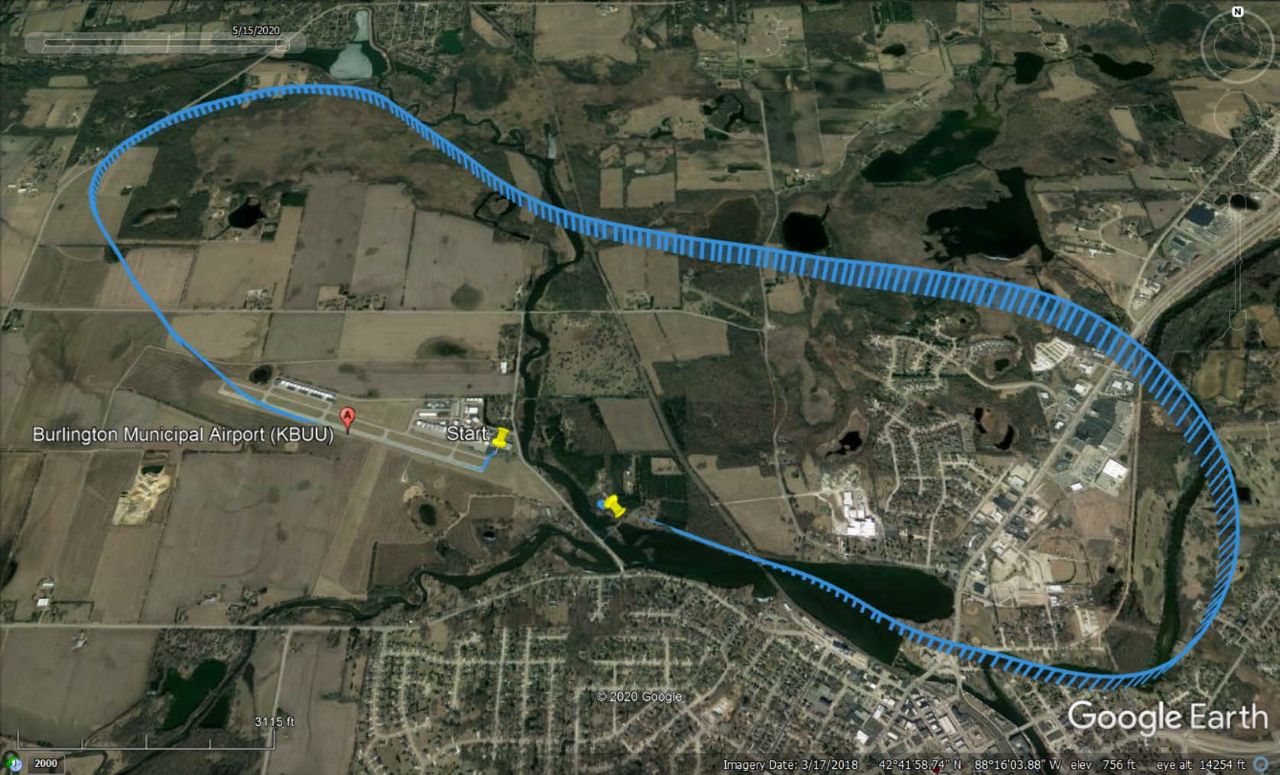

The short and tragic flight path of the accident airplane, a 1978 Cessna P210 Centurion, which crashed, killing the pilot, after the failure of a single component not necessary for continued safe flight. Photo courtesy of NTSB

On May 15, 2020, a well-respected pilot made good decisions and seemed to exhibit safe behaviors---right up to the time when the only thing to do was land. On short final to a quiet country airport, he stalled his Cessna 210, crashed into trees and died. He had been dealing with an electrical problem, but the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) later ruled that issue didn't cause the crash.

The pilot had 15,000 hours of flight time. He had served three years in the U.S. Air Force as a young man and still was passionate about flying. He enjoyed being a flight instructor, including time spent teaching in seaplanes and multi-engine aircraft. His degree was in engineering, and at the time of the accident, he was president/owner of a 35-employee company that manufactures equipment for the mining and construction industry.

He started the day at home, a little north of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In the afternoon, he uneventfully flew his 1978 Cessna P210N Centurion the 45 miles from West Bend Municipal Airport (KETB) to the Burlington Municipal Airport (KBUU) in Burlington, Wisconsin. The P210N is a 310-horsepower pressurized retractable-gear six-seater, a big, capable Cessna. Burlington Municipal is a small, friendly airport, with one 4,300-foot-long asphalt runway and a shorter turf runway. He had an appointment with a familiar maintenance shop. The plan was to "go over some configuration issues between his iPad and panel-mounted avionics and for some in person tutoring on operation of the recently installed GPS and ADS-B transponder." After a productive few hours, the pilot refueled his Centurion and took off, heading back home to West Bend.

He didn't get far. ForeFlight tracking data from his iPad shows him leaving the pattern to the north, then doing a left 270-degree turn, joining the left downwind leg at a 45-degree angle, and landing. All maneuvering seemed smooth and standard. Witnesses said the landing was normal. Why had he returned?

The pilot explained to the mechanic that the horizontal situation indicator (HSI, an upgraded gyroscopic heading indicator) had stopped working soon after takeoff. Looking under the panel didn't reveal any obvious problems, so the mechanic recommended "we run the aircraft and taxi around so I could observe the behavior of the compass system. [The pilot] agreed and we both climbed in the airplane and he started the engine which I noted started very easily and ran very smoothly." While doing taxing turns, they noticed the ammeter was "over on discharge. We tried some troubleshooting of the alternator system and agreed the compass likely stopped functioning due to low voltage."

Back at the shop, the mechanic planned to test the alternator for field voltage. Opening the engine cowling, he saw the root cause of the problems---the belt was missing from the alternator. It was found in "bad shape," broken, laying on the other side of the engine compartment. The pilot had a spare belt in the airplane, and while the mechanic installed it, the pilot and the mechanic's wife relaxed at the quiet country airport. The mechanic noticed nothing else amiss with the engine, tensioned the belt, safety-wired the bolts, closed up the cowling, and inventoried his tools. He bid farewell to the pilot: "[J]ust start it up and verify it charges, if it does you should be all set and just head home. I'll mail the log entry with the bill." The pilot was trying to make a 7 p.m. dinner reservation with his wife.

After a routine engine run-up, he took off at 6:08. The wind was calm, no clouds, good visibility, temperature 73° Fahrenheit. The initial climb appeared normal, but the mechanic noticed the landing gear didn't come up.

The C210 immediately rejoined the traffic pattern, announcing on the radio he was flying a low crosswind leg to join the right downwind. One witness, a CFI (Certified Flight Instructor) listening on the ground, described the pilot's voice on all the calls as sounding normal. There was no sound of trouble. The Cessna turned a square base leg, then lined up on the extended runway centerline.

On final approach, the pilot got low and slow, so slow, in fact, that he stalled the plane, crashing into trees, coming to rest a quarter-mile short of Runway 29. The pilot was conscious but trapped in the strong metal airframe (it was a pressurized version of the C210). First responders kept him alive, and firefighters extricated him from the wreckage. However, he died in the hospital the next day.

After the accident, the mechanic noticed a missed call on his cell phone. The pilot had tried to call him during the short flight. The NTSB later determined that the engine was running fine at the time of the accident. The flight controls were also determined to be in working order.

The one discrepancy was the alternator belt. The NTSB found "postaccident examination of the airplane revealed the replaced alternator belt was displaced from the engine-driven pulley and the alternator and was found lying near the back and bottom of the engine. Although this condition would affect the airplane's electrical system, the displaced belt would not affect the engine power performance." The electrical system was running on battery power. The battery showed 23.76 volts, a little below the nominal voltage of 24, though it was at only 21% capacity.

The NTSB assigned probable cause: "[T]he pilot did not maintain a safe altitude during the visual approach and subsequently lost control, which resulted in an impact with trees and terrain." But why would a respected instructor pilot lose control in perfect weather at a familiar airport? We'll never know for sure. But an old airline accident may be instructive.

Shortly before midnight on Dec. 29, 1972, Eastern Air Lines flight 401, a widebody Lockheed L-1011 TriStar on approach to land at Miami International Airport (KMIA), didn't have a green indication in the nose gear indicator. Was the nose gear down and locked? The pilots cycled the landing gear up and then down again. The nose gear light still wasn't green. The experienced crew of three climbed the plane back up and entered a holding pattern at 2,000 feet above the Everglades to troubleshoot the problem. One of the autopilots was engaged.

Work on the problem they did. The flight engineer and a jump-seating Eastern L-1011 mechanic went down to the avionics bay underneath the cockpit to look out a porthole to get physical confirmation of gear position. The first officer tried to remove and reinstall the nose gear position light lens assembly. The captain, according to the NTSB, "divided his attention between attempts to help the first officer and orders to other crewmembers to try other approaches to the problem."

On final approach, the pilot got low and slow, so slow, in fact, that he stalled the plane, crashing into trees, coming to rest a quarter-mile short of Runway 29. The pilot was conscious but trapped in the strong metal airframe (it was a pressurized version of the C210).

After a while, the autopilot clicked off, and the nose came down a little. The big three-engine jetliner started descending toward the dark swampy river. No one noticed until it was too late, and the plane crashed into the Everglades. One hundred and one people died. The tragic irony was that the gear was, in fact, down, and the only problem with the plane was a burned-out indicator bulb. There were four people in the cockpit, but nobody was watching the flight path. This accident led to a fundamental axiom of modern crew resource management (CRM) --- always have one person fully engaged in flying the plane.

Of course, most pilots don't have large crews to manage. When flying alone, you have to manage your own attention and awareness. You have to prioritize flying the plane, always monitoring heading, airspeed and altitude. The C210 pilot did the right thing by returning to Burlington. Twice. He resisted any pressure to make the restaurant reservation with his wife. And it's admirable he was trying to understand the alternator issue. But maybe he gave too much attention to the electrical problem.

We do know he was trying to make a phone call in the traffic pattern. The NTSB wrote of the Eastern 401 crash, "the flightcrew did not monitor the flight instruments during the final descent until seconds before impact" and "the captain failed to assure that a pilot was monitoring the progress of the aircraft at all times." Almost 50 years after that crash, we all still need to manage distractions and sometimes focus on just flying the plane.

Do you want to read more After the Accident columns? Check out "Fatal Cirrus SR-22 CFIT in Las Vegas" here.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox