Black-Hole Illusion Leads to Fatal Piper PA-32 Crash

The pilot of a PA-32 emerged from the clouds on an instrument approach. That’s when it all went wrong.

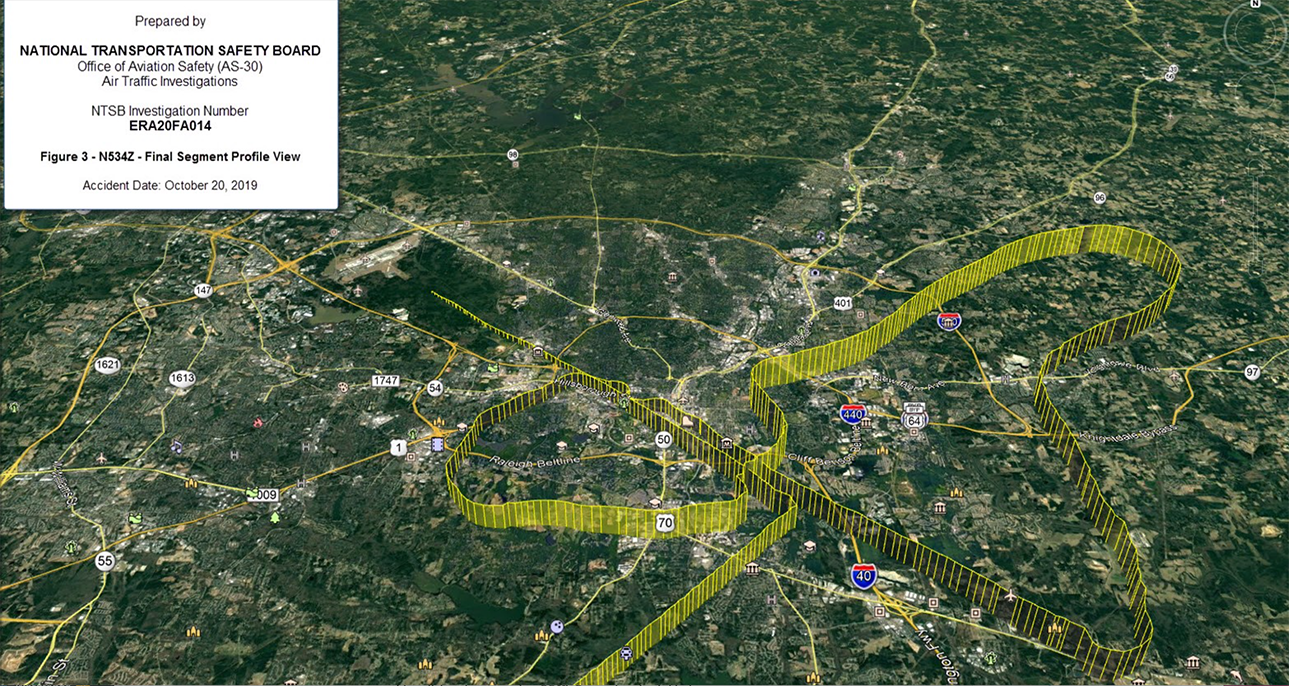

The flight path of the Piper Saratoga on approach to Raleigh-Durham graphically demonstrates the increasing level of confusion as the pilot began the approach sequence.

The pilot of a Piper PA-32 was having some navigation and control problems. He was in the clouds on a night RNAV GPS instrument approach into the Raleigh Durham International Airport (KRDU), North Carolina. Eventually, he broke out of the clouds, seeing the runway straight ahead. But instead of landing, he crashed one mile short of the airport.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) recently released its full report on this Oct. 20, 2019, accident. It carefully details the issues the instrument flight rules (IFR)-rated private pilot had in the clouds. However, the unsafe flight path and resultant crash happened long after the pilot had the runway in sight. Strangely, the NTSB never mentions the treacherous visual illusion that might have killed the pilot and his wife.

The couple had grown up in the same Florida town, they got married at 20 and stayed married for over 50 years. He was a veterinarian who founded a St. Petersburg animal hospital and, in the words of a Tampa Bay newspaper, "was the kind of veterinarian who put his home number in the phone book." After attending a reunion at Auburn University, the couple were flying from the Columbus Airport (KCSG), Georgia, to Raleigh to visit friends. He'd been a pilot for decades, logging almost 3,000 hours. Together, they'd bought their first airplane in the 1990s and had owned several others over the years.

N534Z was a Piper PA-32-301 Saratoga, a comfortable fixed-gear single-engine airplane. It's a 300-horsepower version of the Cherokee Six, a six-seater that looks just like what it is---a larger brother to the popular PA-28 Cherokee. This one was built in 1989 and had club seating in the back and capable avionics up front. In addition to an autopilot and traffic advisory system, it had two big-screen GPS navigation units.

While an experienced pilot, the doctor may not have recently used all those tools in actual instrument conditions. According to the pilot's logbook, he did not meet the recent instrument flight experience and night takeoff and landing requirements of CFR part 61.57 to act as pilot-in-command of an aircraft carrying passengers. His most recent instrument experience was on Nov. 26, 2018, when he logged three instrument approaches. His most recent night experience was logged on Nov. 3, 2018, when he recorded half an hour.

Both of these were more than a year before the accident flight. His Flight Review was still valid, taken in a C172 at the start of 2019. The flight instructor said the doctor was going to New Zealand for an Outback flying tour with a Kiwi guide/instructor and wanted to be comfortable again in a high-wing aircraft after years in low-wings.

At 6:25 p.m., N534Z checked in with Raleigh Durham air traffic control (ATC) at 7,000 feet with the ATIS. The sun had set, the broken ceiling was at 1,000 feet above the ground. There was no precipitation or reduced visibility beneath that cloud deck. Light winds, 62 degrees Fahrenheit, RDU landing north.

ATC told N534Z to expect the RNAV Runway 32 approach. The pilot said he was set up for Runway 5 Right. ATC replied that it could work him in, but 32 would be helpful for jet traffic inbound that needed the longer Runway 5. The pilot agreed and was issued a clearance direct to an initial approach fix and was then cleared for the approach.

Getting closer to the airport, he was switched to the tower frequency and cleared to land. Then things started to fall apart.

Pilot: "Raleigh Approach, 34Z, I need to climb, my GPS, uh, my, uh, my approach just shut off."

ATC: "Okay, N534Z, maintain 3,000."

Pilot: "Can you tell me what my heading is, 236?"

ATC: "Your current heading does appear to be 230, just maintain 3,000 for now."

The tower informed the Saratoga that he'd be re-sequenced for the instrument approach and handed him off to approach control. The pilot of N534Z then told the controller he was having problems with his heading. The pilot requested 4,000 feet to try to get above the clouds. He said his autopilot shut off, and he seemed confused over his position. The controller was comforting, talking slower: "34Z, no problem, looks like you're direct NOSIC at this time, is that correct?"

Pilot: "Ah!er, 34Z, and er!let me figure out what's going on here."

ATC: "34Z, roger, just fly heading of zero five zero, zero five zero for now, and we'll let you get settled and set up, and then we'll bring you back in. Okay?"

Pilot: "Roger."

ATC: "34Z, I'm showing you about 400 feet high, just when able maintain 4,000."

This gentle hand-holding continued for a while. There was pilot confusion over headings, position, the spelling of fixes on the RNAV 32, his altitude drifted up and down, there were turns left and right; then vectors were given to join a straight-in final approach. The Piper was again cleared for the RNAV 32 instrument approach.

Pilot: "34Z, I just broke out."

ATC: "34Z, roger, you got the runway in sight?"

No answer.

ATC: "34Z, you are cleared visual approach Runway 32."

No answer.

ATC: "534Z, you are cleared visual approach Runway 32."

Pilot: "I'm looking for the runway, there's a lot of lights here."

ATC: "34Z---low altitude alert. Maintain 2,000 please. Two thousand."

Pilot: "Two thousand, 34Z."

ATC: "And 34Z, the airport's 12 o'clock and niner miles, you have it in sight?"

Pilot: "I believe I do. I think I see the beacon."

ATC: "34Z, roger. Okay, if you've got the runway, you are cleared visual approach Runway 32."

Pilot: "How am I doing on altitude. I'm 1,400."

ATC: "34Z, your altitude is fine. If you have the airport in sight, if you have 32 in sight, you can do a visual approach, you're cleared a visual approach, Runway 32."

Pilot: "The only thing I see is the beacon."

ATC: "Okay, 34Z, we're going to turn the lights up to see if you can see the runway."

Pilot: "34Z, I think it's coming in now."

Pilot: "34Z, I have the runway in sight."

It was the pilot's last transmission.

He seemed task saturated, possibly facing an autopilot failure and problems sequencing GPS intersections. In the clouds at night at an unfamiliar airport. Unsure of position, requiring ATC radar assistance to join the final course.

Whether there were real equipment problems or just unfamiliarity issues, we'll never know. But breaking out of the clouds and seeing the airport should have left those problems behind and resulted in a routine visual landing.

Instead, the Saratoga flew a constant descent path into the trees. It was missing from radar, no longer in sight from the tower cab, and not answering multiple radio calls. At 7:22 p.m., the controller-in-charge called Crash Fire Rescue services on the dedicated crash phone. The airport was closed for about 20 minutes as the emergency vehicles headed out into the thick woods east of the field looking for the plane. They didn't find it.

It wasn't until 10 o'clock the next morning that search crews discovered the wreckage. It was 1.18 miles from the runway threshold. The lengthy delay gives some idea how heavily wooded the 5,500-acre William B. Umstead State Park is that borders the airport. The initial point of impact was the top of a 100-foot-tall pine tree, where a large section of the right wing remained lodged. The physical evidence was consistent with a descent into the trees at a shallow descent angle. The cause of both deaths was multiple blunt force injuries.

After the accident, toxicological tests were negative for ethanol and common drugs of abuse. The aircraft suffered serious impact damages, but the NTSB could find no pre-existing issues with the airframe or the instruments. The engine was running at the moment of impact.

The instructor pilots who flew the RNAV 32 approach right before the accident airplane were concerned about the plane behind them based on the radio calls they were overhearing. They landed, pulled off on a parallel taxiway and watched the inbound Saratoga through the back window. In an NTSB interview, one of them said, "the pilot was having trouble!sounded confused!the airplane was super stable!he was stable and visual for about 15 seconds!He just descended into the tree line. There was no erratic movement."

Similar to other NTSB statements of probable cause, which merely state the facts of what happened and not why, the Board determined the probable cause to be "the pilot's failure to maintain a safe glide path during final approach to the runway, which resulted in a collision with trees and terrain. Contributing was the pilot's lack of recent instrument flight experience."

One can't help but be reminded of how fragile, how fleeting, instrument currency is. Despite years of experience, skills atrophy fast. But why, when out of the clouds, did this pilot fly way below a safe glide path?

Investigators have identified the black-hole illusion since at least 1947. It's a type of spatial disorientation that occurs on final approach when we don't have the normal visual cues of a reliable horizon and underlying terrain. It's one of the reasons large-approach light systems were designed at the end of runways for low-visibility landings. One FAA guide states, "a particularly hazardous black-hole illusion involves approaching a runway under conditions with no lights before the runway and with city lights or rising terrain beyond the runway. Those conditions may produce the visual illusion of a high-altitude final approach."

We see ourselves as too high, so we unconsciously correct this by descending lower, making the sight picture look right. But we end up physically low. Sometimes very low. The black-hole illusion is well named. When this illusion is present, it seems like a powerful gravity of pure darkness pulls us down. The actual geometry and psychology are still not fully understood, but current university research in simulators finds that the effect is real. Experienced pilots perform worse than low-time pilots, maybe because they trust their visual picture more. We can guard against black-hole illusion by always staying at or above electronic glide paths, always staying at or above visual glide paths like PAPI or VASI, and calculating minimum altitudes to fly on final based on distance from the runway.

In 1974, a Pan American World Airways Boeing 707 crashed just short of Runway 6 in Pago Pago, American Samoa. That accident investigation report was maybe the first to use the term "black hole." In 1997, an Air Sunshine flight crashed on approach to St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands. That NTSB report concluded, "evidence suggests that the absence of visual cues caused by the combination of dark sky and darkness over the water produced a ’black hole' effect in which the pilot lost visual sense of the airplane's height above the water."

The Saratoga pilot was having problems instrument flying, so breaking out into the clear, he may have quickly transitioned to controlling his flight path almost exclusively by using visual signals. Unfortunately, the final approach to Runway 32 at RDU passes directly over a large, completely dark state park. At night, under a 1,000-foot cloud ceiling, there are no lights between the airplane and the runway threshold. There is no horizon and no visible terrain. There are no approach lights. The lights of the airport are all behind the runway. It's a classic black hole scenario, and the NTSB's omission of the black-hole illusion in the probable cause does not help scientists cataloging and researching the accident cause. And it doesn't help pilots guard against the insidious illusion that waits for all of us on some clear dark night.

Do you want to read more After the Accident columns? Check out "Misfueling Leads To Disaster in Kokomo, Indiana" here.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox