Charlie Taylor: The Man Who Made The Wright Brothers Fly

Learn about the career and legacy of the first aircraft mechanic.

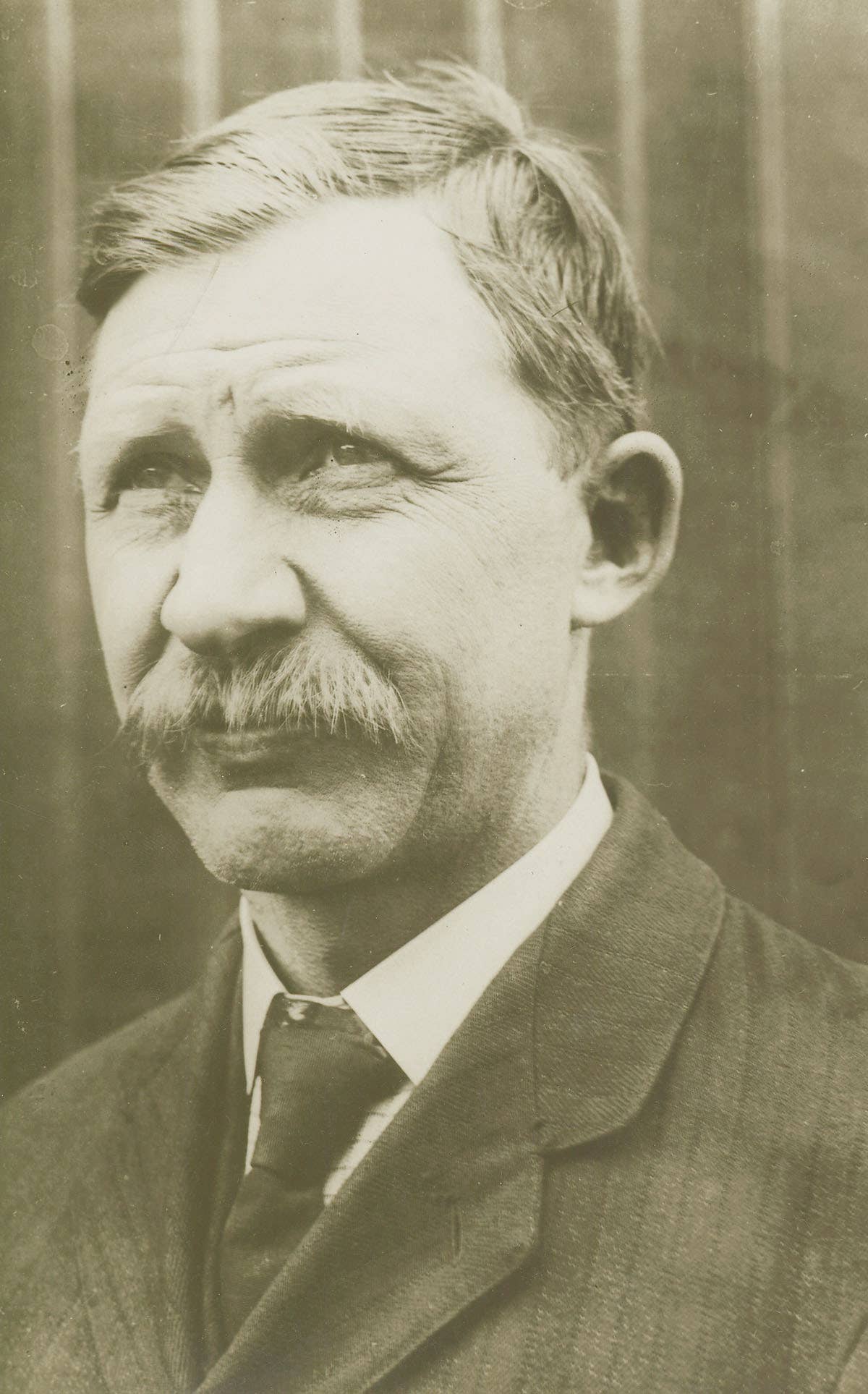

Charlie Taylor. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Public Domain

Orville and Wilbur Wright are widely recognized as pioneers in powered flight, but without Charles E. Taylor, they might never have gotten off the ground. Even though his name has largely been forgotten, "Charlie" Taylor is the man who was able to develop an engine with a sufficient power-to-weight ratio to launch the Wrights at Kitty Hawk and into aviation history. His lightweight and powerful---for its time---1903 Wright engine removed one of the biggest obstacles to powered flight, giving the Wright brothers the edge they needed to take to the skies before their competitors.

Taylor had an innate mechanical ability and was a respected toolmaker. He was working in his own shop when one day Orville and Wilbur Wright came in and asked him to make them some parts. Pleased with Taylor's work, the Wrights continued to bring him special projects---the beginning of a decades-long relationship that would shape the course of aviation history.

Origins

Who was he: The first aircraft mechanic

Original title: Mechanician

Born: Charles Edward Taylor on May 24, 1868

Where: Cerro Gordo, Illinois

Childhood: Grew up in Lincoln, Nebraska

Schooling: Left school at age 12 to go to work, later returned to finish

Graduated: 1887

First job: Errand boy for the Nebraska State Journal, where he discovered his knack for working with tools

Spouse: Married Henrietta Webbert in 1894

Children: One son, two daughters

Settled: Dayton, Ohio

Early Career

Career: Opened his own tool shop in Dayton, Ohio

Job change: Sold his tool shop and went to work at Stoddard Manufacturing, building farm equipment and bicycles

Side gig: Taking on more repairs for the Wright brothers

Career-defining job change: Hired by Wright Brothers to do bike repairs and "mind the shop" in 1901. Later became chief mechanic at the Wright Cycle Company

1903 Wright Engine

Wright brothers' specifications: Needed 9 horsepower and a maximum weight of 180 pounds

Build time: Only 6 weeks!

How: Used hammer, chisel and other hand tools, as well as basic tools, including a drill press and lathe

Power: 12 horsepower

Weight (engine block and crankcase): 152 pounds

Engine block and crankcase: Lightweight, cast aluminum-copper alloy

Cylinder material: Cast iron

Number of cylinders: Four

Cylinder size: Four-inch bore and four-inch stroke

Total displacement: 201 cubic inches

Cooling: Water-cooled

Quirk: No carburetor; instead, gasoline flowed into a shallow pan and engine heat vaporized it

Other Contributions

Wright Flyer parts: Handcrafted all the metal fittings and support wires

Wind tunnel: Machined parts from workshop scraps for the Wright brothers' wind tunnel, enabling their experimentation and data collection

First Fatal Accident

Close call: Narrowly missed becoming the first person to die in a powered airplane accident when someone else took his place at the last minute

First fatality: Army Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge

Seriously injured: Orville Wright

When: Sept. 17, 1908, during a military demonstration flight

Where: Fort Myer, Virginia

First aircraft accident investigator: Taylor examined the accident wreckage to determine the cause of the accident

Probable cause: Delamination of the propeller

Dashed dreams: Taylor asked the Wrights to teach him to fly; however, the brothers refused to teach him because they were afraid that they would lose their talented mechanic

Longtime chief mechanic for the Wrights: At the Wright Cycle Shop; flight operations and school at Huffman Prairie; and the Wright Company, later the Wright-Martin Company

Income: Received a generous salary and later an annuity from the Wright brothers

Later Years

Departure: Left the Wright-Martin Company for California in 1928

Forgotten: Taylor was largely forgotten after he left the Wright-Martin Company

Lost fortune: Lost all his money in a failed real estate investment near the Salton Sea

Poor health: Disabled by a heart attack in 1945

Rediscovered: In 1955 by a journalist who publicized his hardships

Help: Publicity led to funds provided by the Aviation Industries Association to move Taylor to a private sanatorium for treatment

Death: Jan. 30, 1956 (exactly eight years after the death of his friend Orville Wright)

Where: San Fernando, California

Cause: Complications from asthma

Buried: With other aviation pioneers at the Portal of the Folded Wings Shrine to Aviation, Los Angeles, California

Legacy of Charlie Taylor

Last man standing: Taylor outlived both Wright brothers

Witness to aviation history: Saw the first 50 years of flight, from the creation of the first engine to the advent of the jet age

Honored: Inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1965

Charles Taylor Master Mechanic Award: The FAA's most prestigious award for certificated mechanics, recognizing lifetime achievement for technicians who have demonstrated exceptional professionalism, skill and aviation expertise in their field for 50 years

Recognized: His image is featured on the back of the FAA mechanic certificates

Remembered: Today, his birthday is celebrated as National Aviation Maintenance Technician Day

Fun fact: No known relationship to Chuck Taylor, the 1920s basketball player and coach, or the Converse All-Star sneakers that bear his name---though there are plenty of mechanics sporting the stylish sneakers today

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox