Lessons From Flying Aid To Les Cayes, Haiti

Can small planes really help when catastrophe hits? Maybe.

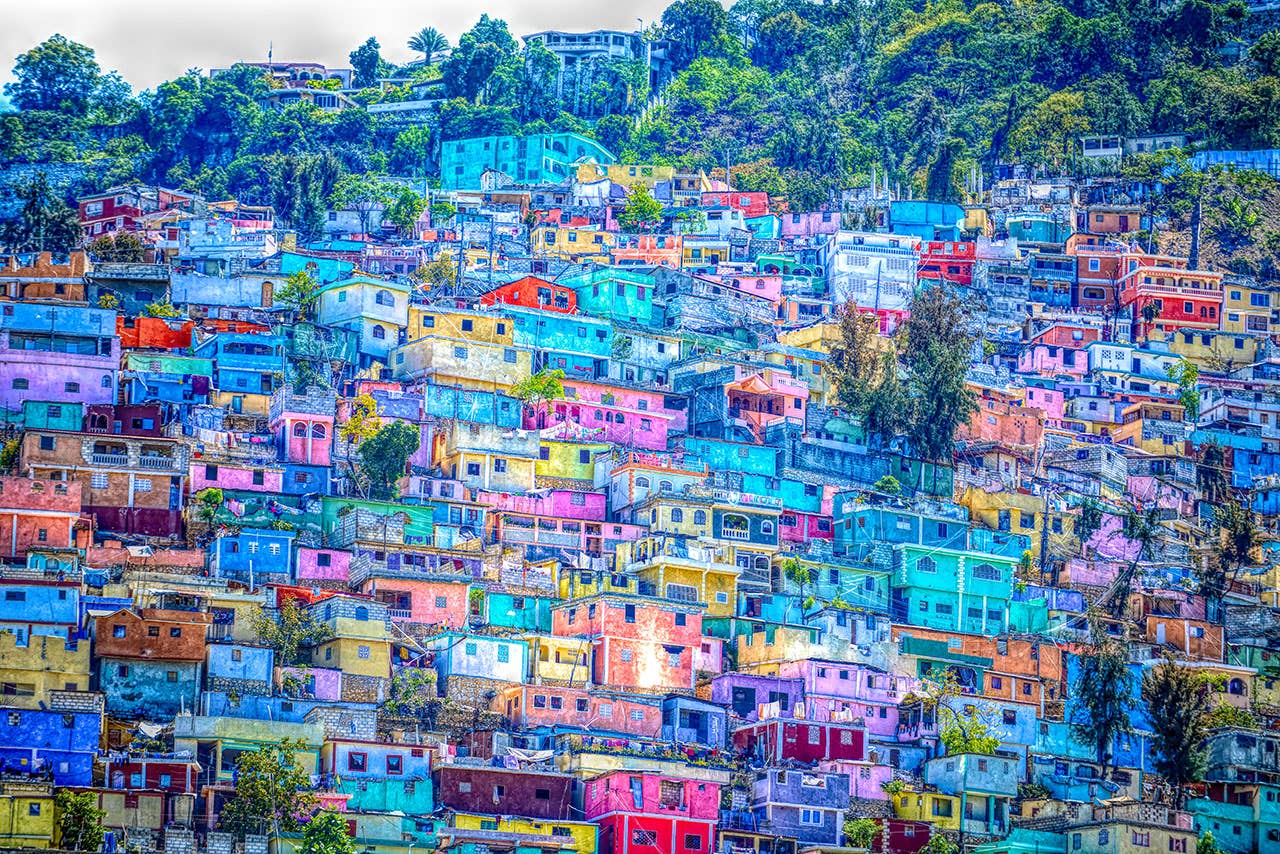

The cities in Haiti are among the most densely populated on the planet. Despite poverty, natural disaster and frequent political unrest, Haitians’ embrace of art and beauty shines through.

In February 2010, an earthquake imploded the city of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, killing nearly 300,000 and injuring more than 1 million. The devastation washed many of the wounded and homeless into the countryside, where they flooded surrounding communities, overwhelmed existing facilities, and spawned new cases of old diseases, including dysentery and cholera.

At the time, I owned a small flight school in central Texas, offering advanced IFR training and tailwheel instruction in my Piper Super Cub.

Previously, following the devastation from Hurricane Katrina, I had joined a group of volunteers who flew relief supplies into Louisiana and Mississippi. We concentrated on supplying the outlying communities, which had been largely overlooked in the rush to help New Orleans. I came away feeling that, if used wisely, general aviation pilots and aircraft could make a meaningful contribution following a similar disaster, particularly in the first days.

As I watched the early reporting from Haiti, it was clear the recovery would require massive aid and, as it was with Katrina, much of it would be targeted at the epicenter, leaving the more distant towns and villages to make the best of it. Knowing there would be a need for volunteers to help move critical supplies into remote regions by general aviation aircraft---a Beech Bonanza, to be more specific---and strangely and strongly compelled to apply what skills and equipment I could offer, I broached the subject with my wife.

"I'd like to go, but it will be challenging."

"Will it be dangerous?" she asked, already knowing.

"Possibly so, and expensive, probably very expensive. How will we afford it?" I asked.

"By faith," she answered. "Somehow, it will all work out. Just promise me you'll be careful."

"I promise and know I couldn't do this without your blessing."

It took a few days to find a charitable organization that wanted our help and understood how to use our capabilities effectively. I made a connection with Bahamas Habitat, a nonprofit that had been providing hurricane relief in the Caribbean for many years. When I called to ask if it could use another pilot and aircraft, the response was, "When can you be in Nassau?"

I recruited Curt, a young private pilot and former student, to accompany me and help with the radio and paperwork. He had only recently completed his private pilot training with me. Knowing he had two young children at home and a business that depended on his personal attention, I doubted that he would be able to join me. He hesitated only long enough to call his wife and quickly committed to the effort.

It took us two days to gather the necessary charts and survival gear, including two SPOT satellite tracking devices. We kept our personal gear to a minimum because every bit of weight saved created more capacity for relief supplies.

With final plans complete, we launched the Beechcraft Bonanza from central Texas, heading for Florida. We spent a night in Fort Lauderdale, where we rented a survival raft, then flew to Nassau, Bahamas, to join a small cadre of doctors, nurses, pilots and aid workers. People of faith, agnostics and atheists united in an ad hoc effort to do something beyond simply writing a check. At the Odyssey FBO, we lived in a donated warehouse, sleeping on the floor, rising early each day to find our airplanes staged and loaded. Eight hours round-trip, across three countries through uncertain weather, mindless bureaucracy, operating without clearances, making it up as we went along.

Because of the distance, we planned a fuel stop in Providenciales, Turks and Caicos. From there, we could make the east coast of Haiti, unload and return once more to Provo for gas before flying back to Nassau. Although we arrived twice each day in Provo, every transit required multiple copies of the same Immigration and Customs paperwork. Curt would fill out much of it in advance, but it cost us significant time at each stop. Three different countries, three different sets of forms, all done twice a day.

"It took us two days to gather the necessary charts and survival gear, including two SPOT satellite tracking devices. We kept our personal gear to a minimum because every bit of weight saved created more capacity for relief supplies."

On one trip into Jacmel, Haiti, we were met at the foot of the airplane by a pleasant young Haitian woman. She asked for information about our flight. I explained that we were bringing a load of medical relief supplies for the local clinic. She thanked us profusely while collecting the $25 landing fee along with the General Declaration forms. We simply shook our heads, smiled politely, and paid the fee. She was one of the fortunate few who had a job, and she was doing as instructed. It did not have to make sense to us.

A typical load would contain bone splints and surgical gloves for the medical teams doing the terrible triage of those who might yet be saved. X-ray developing fluid, crutches and medications were delivered quickly to the aid stations, clinics and tiny hospitals along the eastern coast.

We usually flew under visual flight rules due to the high minimum altitudes required for IFR. The only ATC capability in the vicinity of Haiti was non-radar, and the swarm of airplanes and helicopters going into Port-au-Prince made that unpalatable. Often, the clouds obscured the mountains across the center of the country, so we would climb high enough to assure terrain clearance, then descend below the bases once we were out over the ocean on the eastern side.

I often wondered as we taxied into the chaos of the small airport of Les Cayes, "Was this doing any good? Is any of it getting where it is needed, or is it instead being stolen and sold on some blackest of markets?"

Typically, there would be a crush of people milling around the small cinderblock FBO building, many waiting in the heat and humidity, desperately hoping for a flight out of the country. Ramp space was very tight with several other relief aircraft and helicopters jockeying for position to unload.

Our coordinators back in Nassau always arranged for someone to meet us and collect the 300 pounds of supplies. Often, we would only have a first name, no photo or description. When the designated volunteer emerged from the crowd, we would quickly unload everything, hoping they would deliver them to the proper destination in town. Once unloaded, Curt would complete the various forms and paperwork required, including our outbound Flight Plan. He would hand this across the counter to the Haitian airport official, who would give it a cursory glance before impaling it on a spindle packed with other similar documents. I wondered if anyone would know we had been there if we failed to arrive back in Provo, but the paperwork gods had been placated.

One day we flew a surgeon out to Nassau, and he told us of amputating limbs from an orphaned child. The photo he carried showed a young boy, 6 or 7, heavily bandaged, smiling at the camera with a gap-toothed grin. What thoughts might prompt that joyous expression on the face of such tragedy, I wondered.

Another showed an exhausted nurse consoling a teenaged girl who, living in a country that was a train wreck before, could well be facing a death sentence since there could not be work available for a one-armed young woman. Thousands homeless, no food, no shelter, no clean water!desperation mixed with dysentery.

After nine days, we had done all we could. With fuel bills maxing out our credit cards, physically exhausted, carrying the burdens of so much agony and still wondering if any of our efforts really mattered, surrounded by so much destruction, we knew it was time to leave.

"One day we flew a surgeon out to Nassau, and he told us of amputating limbs from an orphaned child. The photo he carried showed a young boy, 6 or 7, heavily bandaged, smiling at the camera with a gap-toothed grin."

One last load, one more run into Les Cayes. As we taxied in on that beautiful Sunday morning, a crowd of children lined the boundary fence begging for food. This seemed the ultimate futility, but we had nothing more to give, guilt riding with us, knowing that in a few hours, we would leave this misery behind. We were met by a young Haitian aid worker dressed in her pure white habit, who, knowing this was our last trip, thanked us for our efforts. This from a woman who would continue to carry the burden long after we returned to the United States. As we stood together on that quiet morning, still wracked by doubt, not wanting to leave with so much yet undone but knowing we had given all we could, I asked, "Sister, how will this play out? How will these poor people ever recover? It all seems so hopeless."

She paused, thinking of how to respond. From a distance came the sound of hymns. In a grassy opening beside a crumpled church, a small congregation of refugees who, having lost everything and facing not just an uncertain future but also the promise of continued misery and who by rights might have been cursing the god who delivered them into this particular version of hell, instead were singing songs of hope and giving prayers of thanksgiving that lingered in the morning stillness.

Returning my attention to the young Haitian nun, I saw her smile and she whispered!

"By faith!only by faith."

Read "Flying in Hell: Providing Air Support Following The Deepwater Horizon Explosion" to learn how pilots helped following the oil well blowout.

Read "Could An Earthquake Cause A Plane Crash?" to learn how extreme events affect flying.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox