Trim Trouble

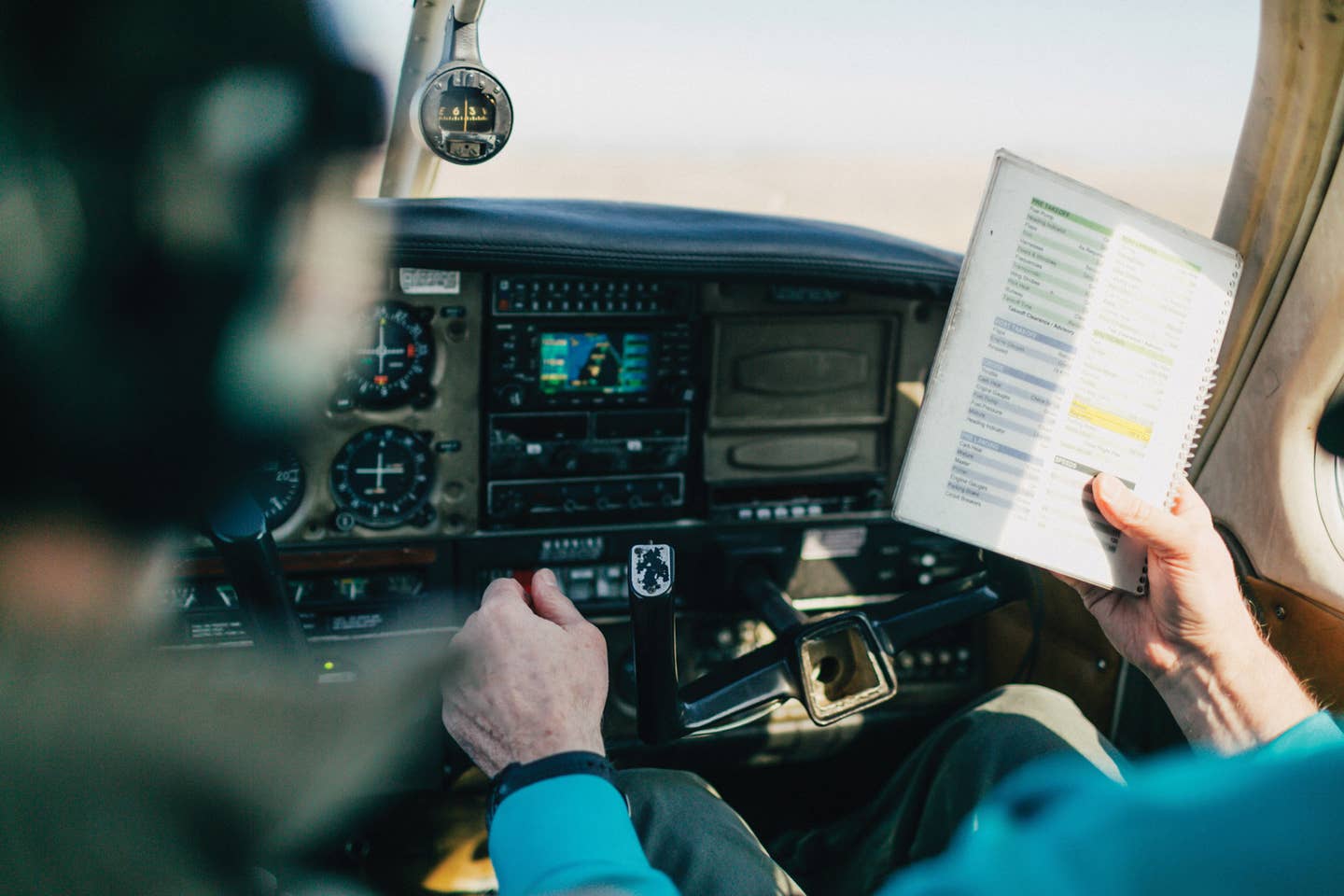

Practicing how to handle runaway controls can prevent a major catastrophe

Many private pilots who were trained in airplanes using manual trim wheels, cranks or knobs have transitioned to aircraft equipped with electric trim without being trained to recognize a runaway trim condition. A malfunctioning trim control switch, relay or other electrical component can cause the trim motor to run out of control, ultimately moving the trim surfaces to dangerous positions. In the blink of an eye, you can find your aircraft lurching out of its smooth cruise configuration into a dive or a stall.

Recurrent training is a good way to emphasize the importance of proper rudder, aileron (when available) and pitch trim settings. You can practice flying with improperly set trim tabs and watch the airplane slipping, skidding or otherwise performing badly. During takeoff, without the trim in the proper position, you're going to have difficulty rotating and climbing. The control inputs to maintain heading and reasonable climb attitude will seem strange. If you're in a twin, you might think an engine is in the process of going belly up. And if you've punched into instrument conditions with a serious trim anomaly, you're really going to have your hands full. Landing an improperly trimmed airplane also can be a daunting task since it's hard to maintain precise control of the airspeed and heading when you're being called upon to apply brute force to the control surfaces.

The NTSB recently finished investigating an accident in which the pilots recognized a trim problem. They thought that they were taking the proper corrective action, but failed to maintain control of the aircraft, which subsequently crashed. They had no way of knowing the true nature of the problem, or that with every spin of the manual pitch trim control wheel, they were inadvertently making the situation worse.

The accident occurred on August 26, 2003, at 3:40 p.m., when flight 9446, a Beech 1900D operated by Colgan Air Inc. (as US Airways Express), was destroyed, crashing into the water near Yarmouth, Mass. The ATP-rated captain and commercial-rated first officer were fatally injured. Visual meteorological conditions prevailed for the flight. The airplane took off from Barnstable Municipal Airport (HYA), Hyannis, Mass., en route to Albany International Airport (ALB), Albany, N.Y. An IFR flight plan was filed for the repositioning flight conducted under Part 91. The airplane had undergone maintenance, which included replacing the forward elevator pitch trim cable. This was the first flight after the maintenance.

The plane departed runway 24 at Hyannis at 3:38 p.m. Shortly after takeoff, the flight crew declared an emergency and reported a "runaway trim." The airplane flew a left turn and reached an altitude of approximately 1,100 feet. After the flight crew requested to land on runway 33, no further transmissions were received.

Witnesses first observed the airplane in a left turn, with a nose-up attitude. The airplane then pitched nose down and impacted the water nose first.

According to the cockpit voice recorder, the flight crew completed the "Before Start" checklist, but there was no record of the "First Flight of the Day" checklist being completed after the engine start. At 3:23:43, the first officer stated, "Preflight is complete. Cockpit scan complete." The captain replied, "Complete."

At 3:23:58, the first officer stated, "Maintenance log, release, checked the aircraft." The captain replied, "Uhhhh. Maintenance and release on aircraft." The captain subsequently identified that the digital flight data recorder (DFDR) was inoperative and confirmed that the minimum equipment list was still open.

The captain began to start the right engine at 3:25:11, but was interrupted. After a conversation with maintenance personnel over the radio, the captain resumed starting the right engine.

After starting both engines, the captain called for the "After Start" checklist. After completing the "After Start" checklist items, the first officer announced the checklist was "complete."

At 3:30:50, while taxiing the airplane, the flight crew began a conversation about the flight plan to ALB and which pilot would fly the airplane. The conversation lasted for about four minutes.

At 3:35:14, during the "Taxi" checklist, the first officer stated, "Three trims are set." The first officer then called the "Taxi" checklist "complete." The flight crew began a non-pertinent discussion about a landing airplane.

At 3:37:00, the airplane was holding short of runway 24. At 3:37:17, the captain stated, "All right. Forty-six is ready." The flight crew then began to announce several items, which were identified as being on the "Before Takeoff" checklist, which wasn't called for. The controller cleared the flight for takeoff on runway 24 at 3:38:07.

A few seconds after the first officer stated, "V1...rotate," the captain declared, "We got a hot trim." The DFDR, which contained data from the flight even though it had been identified by the captain as being inoperative, showed that the elevator trim moved from approximately minus-1.5 degrees (nose down) to minus-three degrees at a speed consistent with the electric trim motor. At 3:38:48, the captain said, "Kill the trim, kill the trim, kill the trim."

At 3:38:50, the captain stated, "Roll back, roll back, roll back, roll back, roll back." According to the DFDR, the elevator trim then moved from approximately minus-three degrees to minus-seven degrees at a speed greater than the capacity of the electric-trim motor. Next, the captain stated, "Do the electric trim disconnect." At 3:39:04, the captain instructed the first officer to "go on the controls" with him.

The captain then instructed the first officer to retract the landing gear, followed by an instruction to retract the flaps. The first officer responded that they were "up." At 3:39:21, the captain radioed an emergency regarding a runaway trim and requested to return to the airport. The controller acknowledged the emergency and offered the option of the left or right downwind for runway 24. At 3:39:33, the captain instructed the first officer to reduce the engine power. The captain instructed the first officer to "pull the breaker." The first officer eventually queried the captain as to its location.

At 3:40:30, the captain requested to land on runway 33. The controller acknowledged the transmission and cleared the flight to land on runway 33.

The recording ended at 3:40:47.

The DFDR indicated that shortly after the captain declared the emergency, the airplane began a left turn while climbing to 1,100 feet. Engine torque was reduced, and the airplane remained at 1,100 feet while maintaining an airspeed of approximately 207 knots and 30 degrees of left bank for 15 seconds. The airplane then pitched down to minus-eight degrees (nose down), and the airspeed increased to 218 knots. The airplane rolled right and left due to control inputs, and the pitch attitude decreased to minus-30 degrees.

The elevator trim system cockpit controls consisted of a manual trim wheel and two switches on each yoke, which activated an electric elevator trim motor. NTSB investigators calculated that at the peak out of trim condition, the flight crew was attempting to counteract control column forces of 250 pounds.

A series of mock-up flights were run in a full-motion Beech 1900D simulator by the chief pilot of Colgan Air and an FAA inspector. During all simulations, the elevator trim was positioned full nose down shortly after takeoff. Five of the six simulations resulted in an uncontrolled descent and crash. On the sixth try, partial control of the airplane was maintained, but the simulated airplane had to land at 180 knots.

The NTSB found that the maintenance technicians who worked on the airplane had not followed steps specified by the manufacturer to ensure that the trim system cables were properly oriented. In addition, the drum around which the trim cables were routed was depicted backward in the manufacturer's maintenance manual. The technicians who performed the maintenance said that they ran the trim several times, and it checked out okay. When another airplane was deliberately misrigged for the investigation, it was found that when the cockpit trim wheel was moved nose down, the elevator trim tabs moved in a nose-up direction. When the cockpit trim wheel was moved nose up, the elevator trim tabs moved nose down. When the electric trim motor was activated in one direction, the elevator tabs moved in the corresponding correct direction, but the trim wheel moved opposite of the electric-trim direction.

The NTSB determined that the probable cause of this accident was the improper replacement of the forward elevator trim cable and subsequent inadequate functional check of the maintenance performed, which resulted in a reversal of the elevator trim system and a loss of control in flight. The flight crew's failure to follow the checklist procedures and the aircraft manufacturer's erroneous depiction of the elevator trim drum in the maintenance manual were contributing factors to the accident.

Peter Katz is editor and publisher of NTSB Reporter, an independent monthly update on aircraft accident investigations and other news concerning the National Transportation Safety Board. To subscribe, write to: NTSB Reporter, Subscription Dept., P.O. Box 831, White Plains, NY 10602-0831.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox