Transatlantic In A Twin Star

An epic journey, in the footsteps of Alcock and Brown

TransAtlantic Twin Star |

This year marks the 90th anniversary of the first nonstop flight across the Atlantic by pioneering aviators Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown (in 1919). They flew most of the way through thick clouds, in an open cockpit, with ice forming on the wings and in their hair. It's almost unbelievable that they found their way to Ireland with only a wobbling compass to guide them. They crash-landed, but got out of the aircraft with only minor cuts and bruises. In order to commemorate their amazing achievement, Paul Lomatschinsky and I made a flight across the Atlantic from Alcock and Brown's departure point, St. John's, Newfoundland, to Ireland and then onward to Wales, U.K. Our flight covered nearly 2,200 miles and demonstrated that flying the Atlantic in a small plane still poses some very real challenges. But first, we had to get our aircraft from its base in France to Newfoundland!

This year marks the 90th anniversary of the first nonstop flight across the Atlantic by pioneering aviators Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown (in 1919). They flew most of the way through thick clouds, in an open cockpit, with ice forming on the wings and in their hair. It's almost unbelievable that they found their way to Ireland with only a wobbling compass to guide them. They crash-landed, but got out of the aircraft with only minor cuts and bruises. In order to commemorate their amazing achievement, Paul Lomatschinsky and I made a flight across the Atlantic from Alcock and Brown's departure point, St. John's, Newfoundland, to Ireland and then onward to Wales, U.K. Our flight covered nearly 2,200 miles and demonstrated that flying the Atlantic in a small plane still poses some very real challenges. But first, we had to get our aircraft from its base in France to Newfoundland!

Getting There: Cannes To St. John's

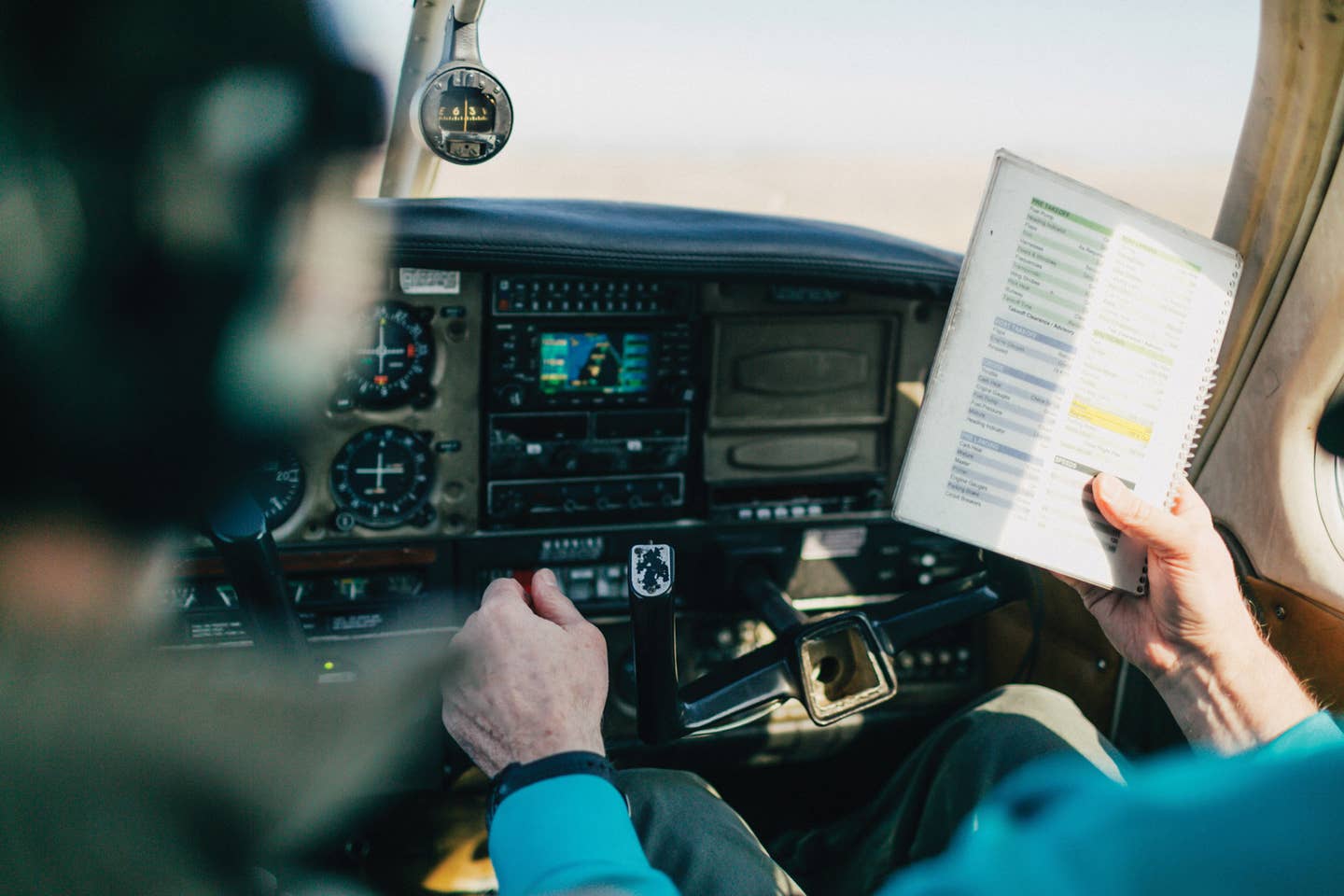

Our first leg is from Cannes, France, to Cardiff, Wales. We taxi our nearly new Diamond Twin Star to runway 30 at Cannes. The sky is strangely overcast, quite different from the usual blue skies of the Mediterranean. We hold on the brakes before accelerating down the runway and rotating at 75 knots. At 3,000 feet, we enter stratus and see the temperature dropping rapidly below freezing. At 8,000 feet, we're still in the clouds, and at minus-10 degrees C, we begin to see a rapid buildup of ice on the leading edges and the engine air intakes. A quick squirt of deicing rapidly clears the leading edges. At 11,000 feet, we break through the clouds, and for the rest of the journey, stay on top. The highlight is a glorious sunset as the enormous orange ball sinks into the clouds, illuminating them from beneath as if they're on fire. The last 90 minutes are at night, with incredibly brilliant stars.

Sefton Potter and Paul Lomatschinsky cross the Atlantic to commemorate the achievements of pioneering aviators Alcock and Brown. |

Early the next morning, we depart VFR to Wick and fly up the spine of Wales, after which Liverpool allows us to join controlled airspace. The journey is uneventful, flying between cloud layers with brief glimpses of stunningly beautiful, snow-covered mountains.

After spending a couple of days in Wick, due to adverse winds and icing conditions, we launch for Reykjavik, Iceland. We're apprehensive: The flight will be our longest, so far, over water---850 miles over the very rough, near-freezing northern Atlantic. The wind is gale force and gusting, which makes opening the canopy and getting in a bit like preparing to get cut in two by a guillotine. This is made all the more difficult by having to wear a total-immersion suit. Fortunately, the strong winds are straight down the runway, which helps us get the heavily fueled plane up into the cold Scottish sky. But we soon learn that the winds aren't quite as forecast, and progress is slowed by 50 mph winds blowing on the nose. We periodically activate the deicing system that covers the wings with a comforting coating of fluid, which should combat the ice that has been forming at an alarming rate. After about six hours, we descend through the clouds into Reykjavik. Once parked, we find chunks of solid ice still attached to the underside of the wings.

Early one morning, we plan our oceanic flight to Goose Bay in Canada. We reckon on 9.5 hours for the cold 1,500 miles. A weather check, however, confronts us with a horrible chart: A big red blob represents severe icing conditions covering 450 miles of our route, which would take about three hours to fly through. Our deice ï¬uid would be exhausted after only half an hour. We consider climbing above the dangerous altitudes, but with two people on board, the oxygen would run out before the blob would. This poses a real dilemma. With just one person on board, however, there would be enough oxygen so that most of the journey could be at 20,000 feet---way above the risk of persistent icing. Though temperatures that high would be much lower (down to minus-25 degrees C), the air would be considerably less moist and much safer for our little plane.

Early one morning, we plan our oceanic flight to Goose Bay in Canada. We reckon on 9.5 hours for the cold 1,500 miles. A weather check, however, confronts us with a horrible chart: A big red blob represents severe icing conditions covering 450 miles of our route, which would take about three hours to fly through. Our deice ï¬uid would be exhausted after only half an hour. We consider climbing above the dangerous altitudes, but with two people on board, the oxygen would run out before the blob would. This poses a real dilemma. With just one person on board, however, there would be enough oxygen so that most of the journey could be at 20,000 feet---way above the risk of persistent icing. Though temperatures that high would be much lower (down to minus-25 degrees C), the air would be considerably less moist and much safer for our little plane.

We reluctantly come to the conclusion that only one of us can safely make the trip---and a few minutes later, Paul taxis away to take our heavily laden bird to Canada. Meanwhile, I'll be organizing enough oxygen in carry-on cylinders to allow us to go all the way at 20,000 feet when I join him for our nonstop transatlantic ï¬ight. Paul makes the 1,500 miles to Goose Bay International safely, but only by flying above the icy clouds for five hours out of the total nine-hour-and-20-minute ï¬ight time. He used more than half the oxygen, confirming that, together, we wouldn't have made it.

Temperatures in Goose Bay have been down to minus-29 degrees C. Our little bird sits in the freezer-like Canadian winter, snowed upon for nine frigid days. On the ninth day, we manage to start one engine, but the prop on the right side is so iced up that it would've shaken the engine to bits if we had tried to start it. We try to taxi with just the left engine running to the area where deicing fluid can be sprayed over the plane, but soon learn (to the amusement of the locals) that taxiing on one engine means driving around in either small or large circles. By the time we've deiced, it's too late to go anywhere, so we head off for caribou steak and chips.

The journey is halted for several days in Goose Bay, Canada, due to minus-29 degree C temperatures. |

Goose Bay becomes our home for three more days due to blizzards there and freezing rain in St. John's, 519 miles away. Finally, we're able to depart, and the views are spectacular: The land, lakes and sea are all a solidly cold shade of white. Beautifully stark. On final approach for runway 29, the wind is gusting to almost 50 mph and blowing straight on the nose, which makes for a turbulent but otherwise straightforward landing. We collect our oxygen supplies and head off to practice our takeoff for our overweight transatlantic ï¬ight. As we climb and circle over the strangely Scottish-looking town and harbor, we realize that we've just followed the same route that Alcock and Brown took on the first transatlantic takeoff in 1919. We land and are very pleased with ourselves that we've finally reached the start of our journey.

The Journey: Nonstop Transatlantic  We wake the next day expecting to plan the greatest flight of our lives. We check the weather. What?! The wind is blowing in the wrong direction across the Atlantic. Severe icing is forecast. We won't have enough fuel to battle that headwind, and even if we did, we would've been ice-cubed and dropped into the white and salty waters. So it's another day spent on the ground.

We wake the next day expecting to plan the greatest flight of our lives. We check the weather. What?! The wind is blowing in the wrong direction across the Atlantic. Severe icing is forecast. We won't have enough fuel to battle that headwind, and even if we did, we would've been ice-cubed and dropped into the white and salty waters. So it's another day spent on the ground.

The next dawn brings good news: The forecast is for 60 to 120 mph tailwinds at 18,000 feet to push us all the way to Europe. No icing conditions above 15,000 feet until Ireland, when we can go much lower. It looks perfect! The countdown starts for a 2:30 a.m. departure.

There's much to do. Fill up the fuel tanks to their 142-gallon capacity. Install the notoriously unreliable 1950s' technology high-frequency (HF) radio (the sole contents of a large suitcase). Buy a satellite phone in case the HF radio doesn't work. Check and recheck every system on the plane. Finally, we've prepared everything except ourselves---but we're too excited to fall asleep. At midnight, I begin a lengthy session of dressing in three cotton vests, two shirts, Lycra running leggings, two pairs of socks, one-piece flying overalls and three pairs of boxer shorts---all of which I intend to wear under my zipped-up immersion suit.

1:45 a.m.: We return to a very dark and cold airport. As we strap into our seats, we're both quieted by the enormity of the task we're about to undertake. ATC gives us our clearance for the route from St. John's to Swansea, and ice is already forming on the inside of the windscreen as we follow the runway lights to line up. I push the throttles fully forward to encourage our very heavy, very small airplane down the tarmac. After just over ¾ of a mile, we reach the takeoff speed of 110 mph. We begin climbing at a rate that even a baby seagull could beat. But we're going up, through wispy clouds creating a thin, silvery layer of frost on the wings, which eerily glisten in tonight's full moon. Oxygen masks on at 10,000 feet; 56 minutes later, we level out at 18,000 feet. Next stop: Europe.

4:30 a.m.: I can no longer feel my toes. Outside it's minus-35 degrees C; inside, it's probably just above zero. We've been on oxygen now for about 90 minutes. I look over to Paul, who for a few moments appears to have nodded off. I give him a nudge when he complains of tingling fingers---classic symptoms of hypoxia. We whack the oxygen supply up to max, which we find is a very effective way of keeping alert.

5:38 a.m.: I reset my clock and we're greeted by a most welcome orange glow as an enormous sun rises through the cloud right on the nose. Our little plane warms like a greenhouse. I can feel my toes again, and Paul can feel his fingers.

8:30 a.m.: Time for a celebratory cup of flasked coffee. (It's a small one: The first opportunity for relief is at least seven hours away.) For some reason, I don't feel hungry, which is just as well (eating anything would be tricky with the oxygen mask on).

10:43 a.m.: We're a long way from anywhere---at the halfway point, about 1,000 miles out into the Atlantic. If we had to ditch, we'd remain conscious for no more than one hour in the near-freezing sea before hypothermia would slowly and painfully close our bodies down. If anything should go wrong now, we know the chances of survival are negligible as it would take several hours to get a vessel anywhere near us. I take my headset off to get the comforting drone of the engines at full volume. I hope to hear that noise for at least another five hours.

| Alcock & Brown |

Alcock and Brown were motivated to make the first transatlantic flight on June 14, 1919, by the offer of a prize of £10,000 (equivalent to more than $750,000 today) put up by the Daily Mail newspaper. Alcock and Brown were motivated to make the first transatlantic flight on June 14, 1919, by the offer of a prize of £10,000 (equivalent to more than $750,000 today) put up by the Daily Mail newspaper.

|

11:30 a.m.: The winds have picked up exactly as forecast, adding the predicted 120 mph to our groundspeed. Nature is being kind to us today.

11:30 a.m.: The winds have picked up exactly as forecast, adding the predicted 120 mph to our groundspeed. Nature is being kind to us today.

2:30 p.m.: We see Ireland! It's 9.5 hours after takeoff, and everything looks perfect. But then Shannon ATC gives us the weather for Swansea: cloud base 100 feet with dense fog. There's a stunned silence: We can't land in those conditions. Cardiff is similar. If we get to Wales and can't land, we'll be on emergency fuel. Visions of Alcock and Brown's crash-landing in an Irish bog flood my head.

3:40 p.m.: We gingerly descend through the cloud, south of Swansea, down to 1,000 feet, but it's as if a white sheet has covered the plane!no land, no sky, just white. We climb back to 1,500 feet and overfly Swansea at 100% power so our welcoming party knows that we've arrived in Wales. We can almost hear them cheer. We head to Cardiff.

4:00 p.m.: Cardiff reports that the cloud is variable with a base of just 100 feet. We have to give it a go.

4:02 p.m.: We hold our breath as we slide down the ILS, popping out of the cloud just above our legal minimum. Seconds later, we touch down for our arrival in Europe! Three minutes later, the airport is closed as the cloud is well and truly on the deck. We're directed to taxi and park next to a 747.

I rapidly go by car back to Swansea where family and friends are waiting to celebrate our successful flight. The journey had taken 12 months to plan and wouldn't have been possible without the support of loved ones, who knew of the potentially lethal dangers lurking above the vast Atlantic. The fact that the trip is still so hazardous in a small plane that has benefitted from a century of aviation technology makes Alcock and Brown's first transatlantic flight in 1919 seem less like a human achievement and more like a miracle.

| Tips For Crossing The Atlantic In A Small Plane |

| 1. Make sure you have enough fuel---ferry tanks are vital. Plan for a two- or three-hour reserve rather than a one-hour reserve. 2. Wait for the right wind. A 100-knot tailwind gets you there fast; a 50-knot headwind means your last landing will be in the Atlantic. 3. Wait for nonicing conditions; even then, it's best to fly high because, surprisingly, airframe ice forms much more slowly at temperatures below minus-20 degrees C. 4. Plan on at least 11 hours if you're flying nonstop. (Don't drink too much!) 5. Take easy-to-eat snacks. 6. Wear a total-immersion suit. It's very uncomfortable, but the only way to survive for more than 10 minutes if you have to ditch in the near-freezing Atlantic. 7. Wear many layers of clothing under the immersion suit---you may need it. 8. Carry a GPS personal locator beacon (PLB)---the Atlantic's a big place, and the chances of being found in an emergency without a PLB are pretty slim. 9. Get an ocean-rated life raft and learn how to use it before you go. 10. Unless you plan to do a solo crossing, choose your copilot carefully because you'll be spending a long time very close to him (or her). Also, remember that your ferry permit may preclude carrying passengers in the overgross condition. 11. You legally need to have a long-range HF radio, but it may not work. 12. Get a satellite phone that will work anywhere on the planet. |

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox

John Alcock (age 27 at the time of the flight), a U.S. citizen, had six years of flying experience, but Arthur Whitten Brown (age 34), a British citizen, had earned his pilot's license only nine months before the pioneering flight. Alcock died in a flying accident six months after completing the transatlantic journey. Brown died in 1948.

John Alcock (age 27 at the time of the flight), a U.S. citizen, had six years of flying experience, but Arthur Whitten Brown (age 34), a British citizen, had earned his pilot's license only nine months before the pioneering flight. Alcock died in a flying accident six months after completing the transatlantic journey. Brown died in 1948.