The Old Barn Dance

Finding a pair of Stinson 10As offers a chance for another restoration occupation.

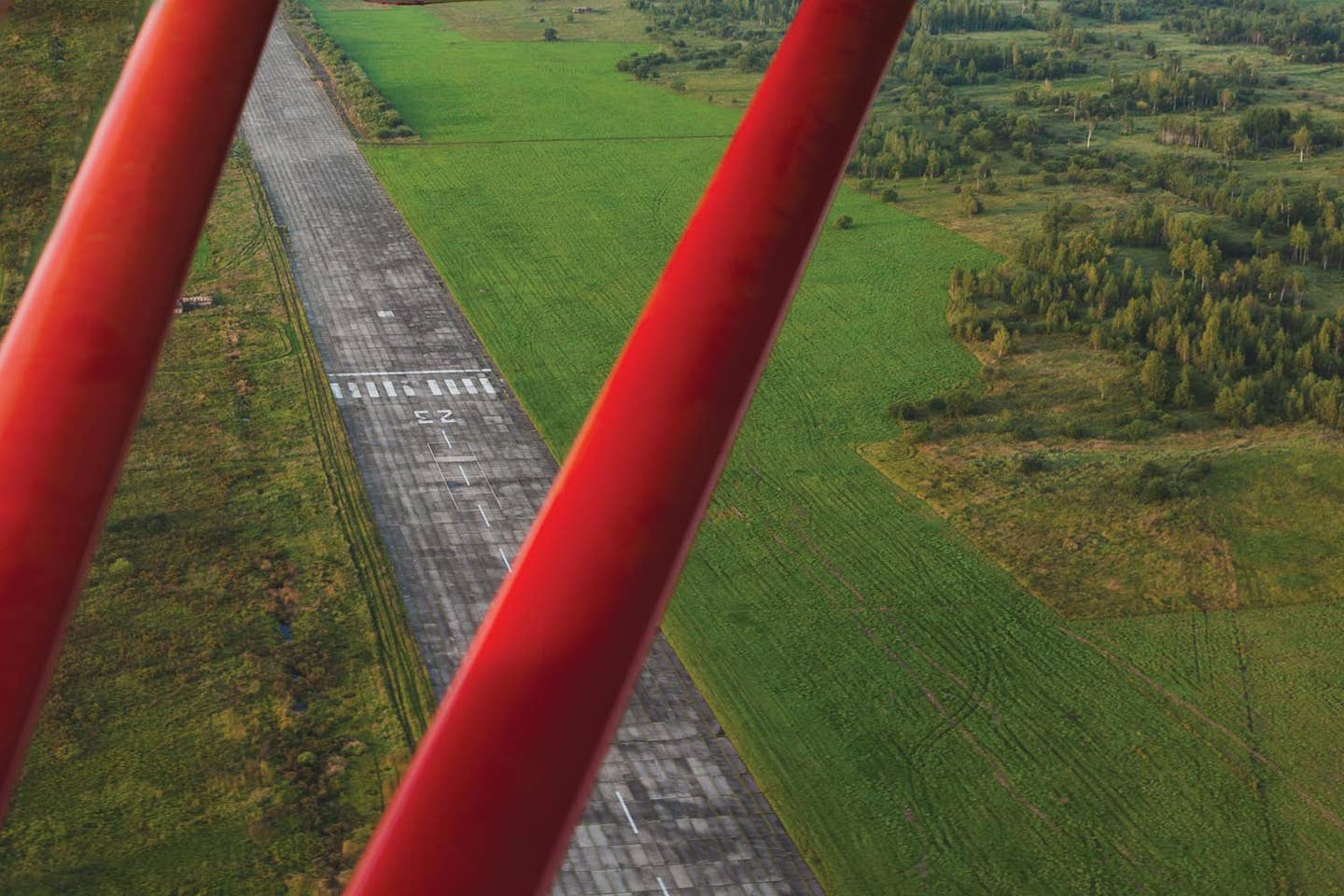

[Image: Adobe Stock]

After getting married in 1990, my wife, Jill, and I spent several years restoring a 1946 Stinson 108. Serial number 256 made this early variant a dash nothing.

The intent was to own an airplane capable of visiting each state in the continental U.S. while hauling a luxurious amount of camping gear. The reality was restoring an older airplane that was significantly more expensive and time-consuming than we had imagined before starting the project. Life happened, and we sold the airplane before ever starting the engine for the first time. When the new owner wrote to tell us the airplane flies beautifully, we felt a great sense of pride in a job well done and the pain of letting the dream slip away.

We are fortunate to currently own a 1946 Taylorcraft BC12-D. It’s a great airplane. For us, the largest knock is limited baggage capacity. Many pilots have successfully camped with a T-Craft. As much as admitting this hurts, both Jill and I wanted a bit more luxury than the placarded 20 pounds of cargo that must fit into the volume of two gallon Ziploc bags. Great for a weekend away, but not so much for our planned extended adventure.

Thirty years later, the dream of putting a landing in each of the lower 48 was reawakened when, on a whim, we stopped to look at a pair of 1941 Stinson 10A Voyagers residing in a barn. There is a romance and lore to the barn-found airplane. The fantasy: discovering some well-preserved classic in need of only a good bath freely given to the dashing young aviator who flies it away from the impeccably manicured farm strip. Our reality: two dissembled airplanes in need of complete restoration before they will ever see the air.

Once the door was slid open we, read I, didn’t see old airplanes. My rose-colored aviator goggles hid the reality of two airframes stripped of fabric now covered in barn dander. We, read I, saw an immaculately restored vintage camping machine capable of delivering us back to the last century when youthful ambition supplanted reality.

We did make an attempt at making practical and rational decisions before taking ownership of the projects. An empty weight of 1,050 pounds (gross 1,680) makes the 10A relatively light compared to other airplanes of similar size and performance. The hope is to have an airplane easier to push around as we get older.

The useful load is 630 pounds before adding 40 gallons of fuel, leaving 384 pounds for us and our stuff. The 10A has seating for three, with the rear passenger sitting transverse to the fuselage. The rear seat is made for easy removal. The rear seating area has enough volume to bring lightweight items and those too large for the gallon Ziploc bag. The 10A has a full electrical system enabling better avionics, no more routine hand propping, and the ability to fly at night.

After careful consideration and no regard for past experience restoring older airplanes, lust overthrew pragmatism, so we took possession of this barn find. Fueled (maybe blinded) by excitement, the pair of airplanes was loaded into a 24-foot rental truck and deposited at home into one bay of the garage in wait for the work to begin

After going through many boxes, we have more than two airplanes’ worth of parts. Jay, the seller, had similar ideas of touring around in the 10A and wanted a cache of spare parts. Digging through logbooks and FAA records revealed that one of the airplanes (MIL) has a military history with the Illinois Civil Air Patrol. The other (CIV) spent its entire life as a civilian-registered airplane.

The temptation (maybe the smart play) is to use the best parts from both aircraft to make one really nice flying machine. Using existing parts is much faster and more convenient than making or sourcing new ones. Spare parts might be nice to have, considering the age of the airplane. Storing most of an airplane takes up a lot of space, and preparing the parts for storage takes almost as much, if not more, time than bringing them to serviceability. If we have to refurbish and store parts, they might as well be assembled into an airplane. The solution: Rebuild two 10As at the same time.

Creating jigs often is more work than building the parts the jigs were created for. The horizontal stabs, spars, and fuselage formers used in the 10A are all made of wood. Laminated compound curves make up the leading edge and main spar of the stab. The main wing spars are tapered in two directions, have multiple doublers per spar, and many aluminum-sleeved bolt holes. Once the forms and jigs are made, creating another piece is relatively simple—just add wood. Jigs and forms take up a lot of space, and with no intention of building more 10A stabs, the jigs can be repurposed and not stashed away for my children to deal with after my demise.

Both airplanes came complete with 90 hp 4-cylinder Franklin model 4AC-199-E3 engines. The E3 model has dual ignition, starter, and generator. These engines are not produced or supported anymore, and the hope is being able to have enough parts from the two engines to make up one reliable power plant. To help with serviceability and parts acquisition, the engines will be sent for overhaul and modifications, allowing bearings from the less exotic and somewhat supported 150 hp engines to be used.

Here is where the similarities of the restorations diverge. Most pilots name their airplanes, and we have bestowed the nicknames of MIL and CIV to our project ships. MIL is slated to be a restoration to its military service and be as accurate as we can make it. Control cables will be woven and not Nicopressed together. Wires, hoses, diamond tread tires, and avionics will be updated for safety sake while the look of the 1940s is emulated. We have period-correct radios, and the modern bits and bobs will need to be hidden in order to preserve the true vintage look. If all goes to plan, it will look as it did when delivered to the Illinois Wing of the CAP back in 1941.

During World War II, the mission of the 10A with the CAP was submarine patrol along the East Coast. A single 100-pound bomb was secured between the landing gear in case a German U-boat was encountered. Preliminary research of our 10A shows it spent its time with the CAP in Illinois with no operational use for sub hunting. A hard point for a bomb rack was installed at some point, and it has yet to be determined if the airplane ever carried a bomb for any purpose.

CIV was ground looped and damaged back in the 1980s. The fuselage is bent near the gear-attach points, wing spars have split, and the lift struts on the right side need replacing. CIV is envisioned as more of a rebuild with a bit of hot rodding. The plan is to install a larger engine, which should improve takeoff and climb performance. The mountains out west are significantly bigger than found in New England. We have the engine mount, and there is an STC to hang an O-230 up front—maybe even something bigger. Add oversized wheels and tires to enable access to less-improved fields. Update the avionics and don’t worry about hiding them. Tinted windows, chrome trim, fuzzy dice, candy apple paint job…you get the idea.

Having rebuilt three airplanes, this wishful thinker is well aware of the pitfalls to completing even one of the 10A projects. Finding the time, money, endurance, and most of all staying interested in the project all play a part in a successful outcome. Want an inexpensive aircraft to get into the air? Just go buy something ready to fly. From experience we are aware that not much is more costly than a free airplane.

These are the plans, visions, hopes, or dreams. The rub is turning these ideals into a reality. There is a certain romance to finding an old airplane in a barn, restoring and then flying it to numerous adventures. The sad truth is many of these barn finds move from one barn to the next while accumulating a bit of degradation with each new home. Eventually, the airplane gets sold off as scrap, and the dream expires along with the dreamer.

Restoring airplanes, like piloting them, has risks involved—but this is part of the fun. Each airplane we rebuilt was easier than the previous one. The workmanship is definitely better. Less time is spent wondering what to do next. Milling wing spars from a blank is new, and figuring out how to build them is truly enjoyable. Reaching out to fellow type owners is a great way to meet people and extend the social aspects of the aviation community.

We didn’t get to fly the 108, but we still had a lot of fun with that airplane. Now we are older, not any wiser, and plan on having twice as much fun with the next installment of the Stinson restorations.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox