Permission to land? A fuel leak grounds a Piper Mirage and pilot Bill Cox in the middle of the Pacific. |

Majuro in the Marshall Islands has to be one of the world's more remote locations. It's smack in the middle of the Pacific, 1,600 miles east of Guam and 2,000 miles southwest of Hawaii.

Until a few years ago, when Mobil stopped refining avgas, Majuro was a standard stop for piston aircraft on the road to Australia, Japan and points in and around Indonesia. I made perhaps two-dozen trips through the Marshalls in the 1990s, flying mostly new Mooneys, Cessna 206s and Piper Mirages to or from Australia and Japan. In case you never heard of the Marshalls, think Bikini Atoll. Does that clarify things?

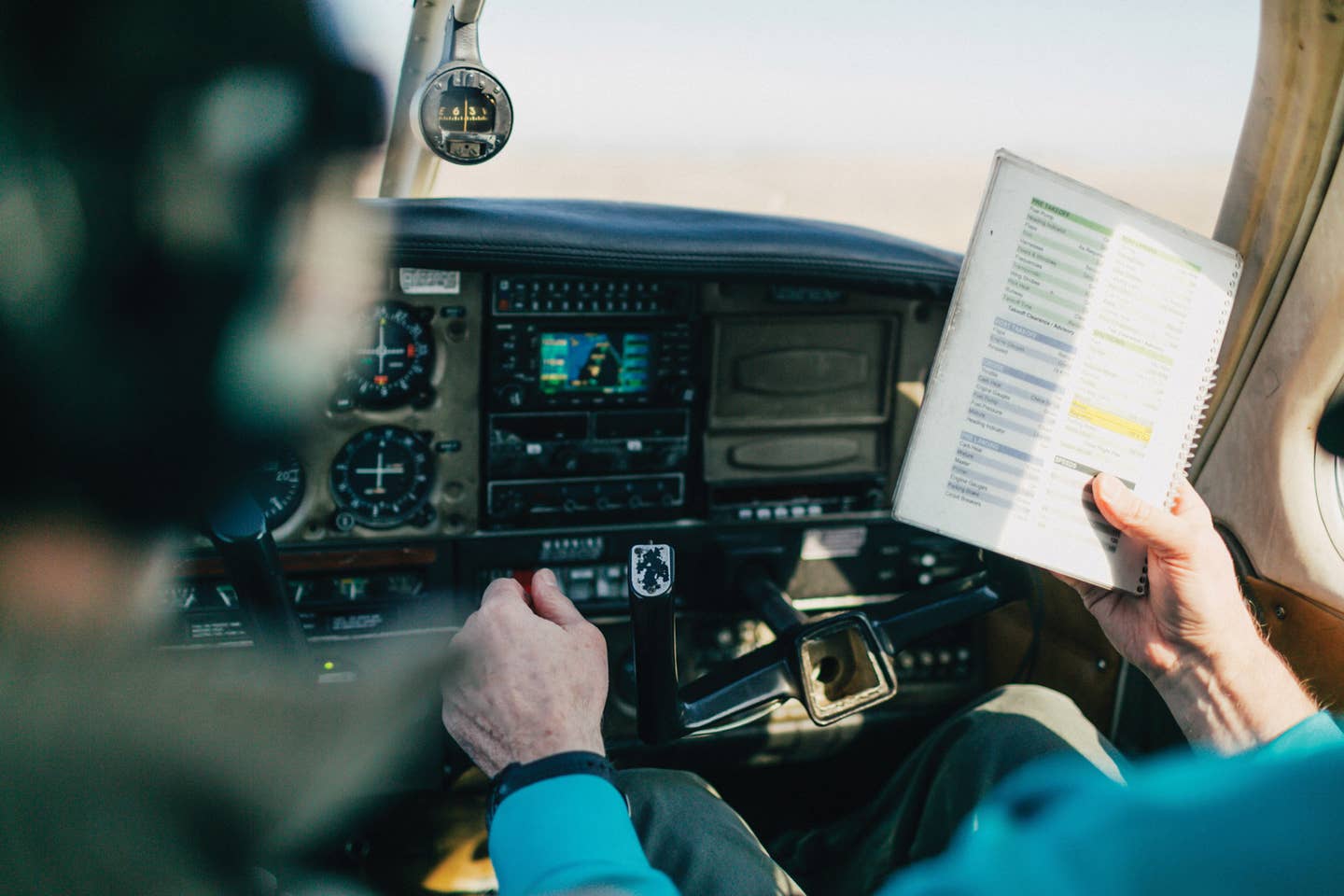

On one ferry flight eastbound from Sendai, Japan, to Aachen, Germany, (don't ask!) in 1999, I was flying a near-new Mirage with a bladder ferry tank in back. This was my first (and thankfully only) trip with a rubber bladder tank, and I was eager to be done with it. Read on.

I departed Majuro at 6:30 a.m. and climbed out toward the next landfall, Johnston Island, which is almost 1,300 miles away and directly online to Honolulu. Predictable trades were in my face all the way, subtracting perhaps 15 to 20 knots from the airplane's 200-knot true airspeed at FL210. The Pacific was benign on that smooth, clear morning in May as I tracked backwards in time toward yesterday and Honolulu, 20 degrees on the front side of the International Date Line.

Just over seven hours out, Johnston came into view far ahead, partially hidden beneath popcorn cumulus that were beginning to materialize as the day heated up. The Mirage was flying smoothly and happily, and so was I as we tracked on toward Honolulu at 180 knots.

The faint odor of avgas is nearly constant in tanked ferry airplanes, but as I closed on Johnston, the fuel odor became stronger. Within a few minutes, it was obvious I had a leak in the ferry tank, and the odor was becoming overpowering.

I initiated an emergency descent to 10,000 feet, dumped the cabin, popped open the left storm window and leaned forward to breathe the cool Pacific air. Johnston was only 30 miles away now; a rectangular island totally covered by a 9,000-foot runway, hangars and a clutch of suspicious Quonset huts cluttering its surface.

Johnston was the worst-kept secret in the Pacific. Seemingly everyone knew it was America's repository for chemical and biological weapons, and the U.S. Navy was systematically burning them up in furnaces at the southwest corner of the island. The trades blow so consistently across Johnston from Hawaii that the smoke plume nearly always blows straight toward the Marshalls, 1,300 nm away with not even a rock in between. If there was ever an accidental release of chemical or biological agents, it would have plenty of time and distance to dissipate. (Still, traditional wisdom in the general aviation ferry business was never to cross Johnston below 10,000 feet. "Doctor, I have this strange cough!")

For obvious reasons, landing at Johnston was strictly prohibited, unless you had a real emergency. Running short of fuel wasn't considered a real emergency. A Beech Baron A55 on the same route had landed there two weeks before when the pilot's "howgoesit" suggested he'd misjudged the winds and wouldn't make Kauai---the Navy hadn't been sympathetic. With not a drop of avgas on the island, they put the pilot on the first military shuttle back to Honolulu, where he had to arrange for a shipment of two barrels of fuel to Johnston. He then returned, refueled the airplane and continued the trip. Subtract $5,000 from his potential profit.

I dialed up Johnston's frequency and punched the push-to-talk. "Johnston, November 3274B, we're 30 southwest out of Majuro for Honolulu, and it looks as if we have a fuel leak in a ferry tank." Short pause, then, "Roger, 74B, this is Johnston, how may we be of service?"

He doesn't get it, I thought. "Johnston, I don't know how long I've been leaking or how much fuel I've lost. The fuel odor is pretty overpowering," I said.

Long pause, then, "Sir, you have to say the words," came the bored reply.

I relented. "Okay, Johnston, November 3274B is declaring an emergency."

"Roger that, 74B. Altimeter is 30.01, wind is 030 at 12, and active runway is 05. Would you like the equipment?" Still bored.

"Negative on the equipment, Johnston," I said. "I'm okay so far. I'll enter a left downwind for 05."

"I understand, 74B. By the way, we'd suggest you not fly through the plume of smoke coming off the smokestacks at the southwest corner of the island." Hmmm.

I turned tight to avoid the ominous smoke, landed and taxied to the small terminal building where a Jeep full of shore patrol cops was waiting---with weapons. They were friendly enough, but also very businesslike. While a young lieutenant JG was checking my paperwork, another shore patrolman climbed into the Mirage, rummaged around inside for a few minutes, then came out, nearly staggering as he climbed down the bottom clamshell.

"Jeez, he's right sir, he has a bad fuel leak. There's nothing in the airplane," the chief told his lieutenant, shaking his head from the fumes. We could see a constant trickle of fuel leaking from the Mirage's belly. The officer smiled, handed back my license and medical, then said, "Okay, sir, it appears you had a legitimate emergency, but you need to fix it and leave. This is a secret military installation and we have no facilities for civilians here."

While the shore patrol looked on, I went back to the airplane and discovered the source of the leak in about 30 seconds, a cracked, clear plastic fuel line coming out of the bottom of the rubber tank. Fortunately, there was plenty of extra tubing, so I pulled out my trusty Swiss Army knife, sliced a new length, clamped it in place and was ready to continue in about five minutes.

Trouble was, now what? How much fuel had I lost? The 150-gallon rubber tank gave me no clue. How much less bulbous should it be when there are five gallons missing? Twenty gallons? How about 30? The leak seemed so small, I couldn't imagine I'd lost much fuel, but I had no way of knowing for sure.

It was 640 miles to Kauai, 700 to Honolulu. While the Navy had assured me I wasn't in trouble, they'd also made it clear I had to leave. Now.

I made a SWAG estimate of remaining fuel, called the tower and had them put me back on file for Honolulu, and departed Johnston with an uneasy feeling. The plan was to run the fat ferry tank until it was flat, then switch back to the mains and finish the trip with some idea of known quantity.

This time, I climbed up to 15,000 feet and began tracking R584 toward Choko intersection and Honolulu. Before I'd gone far, the depth of my stupidity overwhelmed me. I was crossing the Pacific Ocean, and I didn't know how much fuel I had on board. I punched the mic button on the HF and told San Francisco that I was diverting to Kauai. I turned slightly left, cranked the identifier for Kauai into the GPS, and hoped the wind would be a little friendlier on the new heading.

It wasn't. Instead, the Mirage lost about 10 knots as I plunged on through gathering darkness.

As I closed on Kauai and finally saw the lights of the island appear in the distance, I was back on the main tanks, having long since exhausted the rubber ferry tank. My GPS counted down the miles at a glacial speed as both wing fuel gauges dropped toward zero.

I crossed the coast, spotted the rabbit and followed the lights to the most welcome touchdown I've made anywhere in the world. Nine gallons. That was the answer to the big question the next day. That's about a half hour in a Mirage, and if that seems like a lot, remember that I started the day with 270. When we're in our right minds out on the ocean, we like to land with two hours of reserve.

I'll certainly never make that mistake again. Next time, I'll find some new ones.

Bill Cox is entering his third decade as a senior contributor to Plane & Pilot. He provides consulting for media, entertainment and aviation concerns worldwide. E-mail him at flybillcox@aol.com.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox