Into Africa

A pilot returns to a place of special meaning for him, only this time he’s in the cockpit

Kenya occupies a special place in the heart of many of us who love aviation. It features some of the world's most legendary landscapes and wildlife---much of which even today is best appreciated and accessed by airplane. No surprise, then, that it's also been home to several of history's most legendary early aviators.

Perhaps the most famous is Beryl Markham. Markham was born in Britain in 1902 and arrived in what was then British East Africa when she was four. She became a bush pilot, helping to locate game for safaris, and in 1936 she became the first person to fly nonstop, from east to west, from England to North America. She was honored with a tickertape parade in New York City.

Markham's personal life was colorful. One of her lovers (and flight instructors), Tom Campbell Black, was himself a famous aviator associated with Kenya. He taught Markham the mnemonic "variation west, magnetic best. Variation east, magnetic least"---some things never change!---which she repeated aloud during her famous Atlantic crossing. With his co-owners, Black registered the first-ever aircraft in Kenya in 1928---a de Havilland DH.51 (registration: G-KAA; name: Miss Kenya, of course). In the 1930s, he was closely involved with Wilson Airways, an early Kenyan airline, and in 1934, he and C.W.A. Scott won the legendary England to Melbourne, Australia, air race with a time of just over 71 hours.

Markham also dated Denys Finch Hatton, the pilot played by Robert Redford in the movie Out of Africa (Markham's character appears in the movie, too, as the restless, anti-establishment Felicity). Like Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, with whom Markham was also involved---I said her life was colorful, didn't I?---Markham was a legend both in the cockpit and on the page. While I'm partial to the descriptions of flying in the book by Isak Dinesen that Out of Africa is based on---in fact, they're among my favorites passages in all of literature---no less an authority than Ernest Hemingway called Markham's memoir West with the Night "a bloody wonderful book." If you haven't read it, it's time to start dropping hints to your loved ones about holiday gift ideas.

For some of the more "av-geeky" aspects of Kenya's aviation history, it's worth turning to Aviation Week's online archive. One of the earliest references there to Nairobi is a 1919 article describing a plan to start airship services from Europe to Nairobi, carrying 15 tons of "passengers and mails" at speeds of up to 60 mph---taking a mere three and a half days to reach Nairobi from Europe! A 1930 story refers to the anticipated completion of a survey of a new route from England to "Cape Colony," i.e., Cape Town, by Imperial Airways (a predecessor of my employer, British Airways). One of the many planned en route stops was Nairobi. The article states, "It is expected that service will be inaugurated as soon as ground organization is ready"---quite a task. I wonder if those who executed it in the 1930s could imagine the day when planes would easily travel nonstop from London to Nairobi or Cape Town.

A 1959 story refers to FAA inspectors checking VOR beacons near Nairobi, and a 1963 article on the debut of the Comet draws attention to the lack of en route navigational aids in those days, describing how "celestial navigation must be used for periods as long as three hours" on the Nairobi-Karachi route. The brightness, depth and sheer number of stars are some of my favorite aspects of flying at night, and it's quite something to remember that pilots a half-century ago might routinely fly by reference to them for hours on end.

As an airline pilot, this history is deeply fascinating to me. But Kenya and flying have a more personal resonance, as well. In 1998, I was in graduate school, studying history when I was sent from London to Nairobi to spend a year doing research. The first clue that I might be in the wrong line of work was that I was way, way more excited about flying to Nairobi than I was about the historical documents I was meant to study when I got there. Having eventually decided to leave my graduate program, it was on the flight from Kenya back to London that I met the crew, and the first officer strongly encouraged me to follow my childhood dream of becoming an airline pilot.

That dream eventually came true. After a few years in the business world, I started my flight training in Britain in 2001, on a program sponsored by British Airways. I flew the Airbus A320-series jets on shorthaul routes from London Heathrow until 2007, when I switched to the Boeing 747-400, the plane I'd spent much of my childhood looking up to both figuratively and literally. I've been flying that lovely aircraft for nine years now---where does the time go?---but in all those years I'd never flown back to Nairobi.

Until last week, that is, when I checked in at Heathrow for the BA65 from London Heathrow to Nairobi. I was more excited than I've been at work in years. Not as excited as I was about my first solo in a Piper, or my first flight on the 747---but still, pretty darn excited, to be flying back as a pilot to the very city I'd left in order to become one.

So here I am at Heathrow airport, and I can't quite believe it's my job to check the headline figures on our iPad briefing documents for a flight to Nairobi. Our flight time is eight hours and 30 minutes, to cover 4,041 nautical miles. Our trip fuel is 87,942 kilograms. Our destination alternate is EBB, or Entebbe, the airport that serves Kampala, the capital of Uganda. Add in the various reserves, and all told, our fuel load amounts to 106,013 kg. With a payload of 40,500 kg, our takeoff weight is 334,200 kg and our expected landing weight is 246,300 kg.

I download the route into my iPad and look at the various countries and Flight Information Regions it crosses. The route varies each day with the winds, of course. I've flown the first portion of today's route before, on flights to Cairo and Saudi Arabia, so the first four hours or so of the flight are familiar territory for me. After takeoff from London we cross the English Channel, then route over Belgium, Germany, Austria and Italy. We see the Alps and Venice. Then it's down the Adriatic coast to fly just to the west of Athens and then over the western tip of Crete.

Next up is the Egyptian coastline west of Alexandria, and from there it's all new airspace for me, though not for my two colleagues. I'm glad the outbound leg is in daylight. Once we leave the coast behind, the desert below looks beautiful and all but empty, except for the occasional straight line of a road that leads the eye to a small settlement. We cross the Nile Valley (although it's actually on the return leg to London, at night, that we get the best view of the world's most famous river, flowing across the surrounding darkness and shimmering in the light of the full moon), then Sudan and the highlands of Ethiopia, dotted with showers we occasionally have to navigate around. Soon enough the sun is setting, we're crossing the equator, and it's time to start our descent into Nairobi.

Operationally, the most interesting aspects of Nairobi's Jomo Kenyatta International Airport---named for independent Kenya's first leader---are its elevation and the surrounding terrain. The airport elevation is around 5,300 feet---so Nairobi is a "mile-high" city like Denver. That elevation is actually similar to our cabin altitude in the cruise, so there's very little ear popping during the descent, which everyone onboard appreciates, especially our youngest customers (not to mention their parents!). The elevation also means that we carry out our usual FL200 and FL100/10,000 feet altimeter checks at FL250 and FL150/15,000 feet instead, so that their role in maintaining our situational awareness is unchanged.

To the north of the airport, MSAs rise to over 15,000 feet, and then to over 19,000 feet in the direction of Mount Kenya, the peak that is the second-highest in Africa---and that gave its name to the country of Kenya itself. Further away, to the south, is Tanzania's Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa's tallest mountain---visible during daytime arrivals, and even from downtown Nairobi on a clear day, or so I'm told.

It's a fine evening and we see the lights of Nairobi from many miles away. The skies are quiet and we're soon cleared for an ILS approach onto runway 06. In terms of landscape, climate, scenery and actual miles, we're a long way from the magnetic pole in northern Canada. Magnetic variation here is just one degree east.

The elevation of Nairobi and the above-ISA temperature---it's 19 degrees Celsius on the deck---mean that our indicated airspeed at landing of 155 knots equates to a true airspeed of more than 170 knots, a decent clip for a 747. No surprise, then, that the runway here is longer than most, 4,117 meters, or 13,502 feet, enough, perhaps, for a short takeoff, flight and landing in a Cessna 152! We land with flaps set to the 747's maximum of 30 degrees---and if you've never seen a jumbo approaching with flaps 30, I encourage you to check out a picture online. It's a remarkable feat of engineering that echoes the natural form of some majestic bird with its wings fully spread. To quote one of my colleagues, the flaps look almost like an entire second wing that we've extended from the first. We use full reverse to assist the wheel brakes and make an early turnoff toward the terminal.

After the shutdown checklist is complete, there's a quiet moment during which I realize---with a smile---just how long a journey I've been on. Here I am, back in Nairobi as a pilot, 18 years after I left with only vague hopes of ever becoming one. I never dreamed that I would return, least of all on the flight deck of a 747. As I walk off the jet into the high Kenyan air, these memories are a reminder to think of all the hundreds of customers we've carried today---and of all the stories of Kenya, Britain and elsewhere that this flight will form a part of for them.

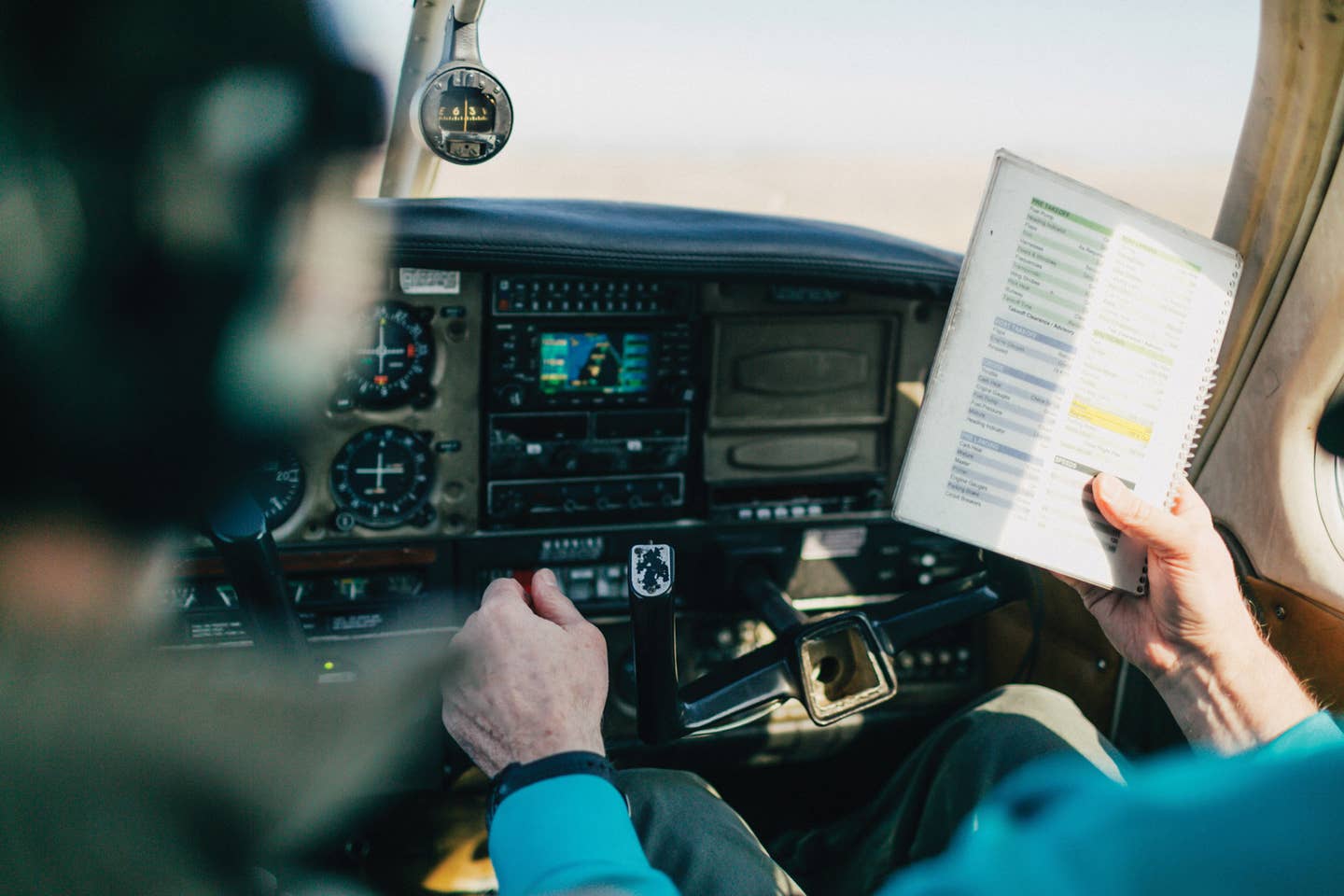

The numerous light aircraft in the skies over Kenya are a reminder of how important aviation remains for the country---especially in terms of transporting people to and from the safari locations that are so crucial to the country's economy.

To get a sense of these "bush" facilities, check out the website of the Aero Club of East Africa (aeroclubea.com), a venerable institution that has existed since 1927 (and feel free to contact them, they said, if you're planning a trip to Kenya and would like to learn more about light aircraft flying here). Their website has short, but eye-opening briefs for many of the makeshift fields that serve safari camps in the wilderness. At one, aviators are advised, "Remember that wildlife has the right-of-way and that if they decide to remain grazing on the runway you will have to divert to an alternate." At another, they warn, wildlife may crowd on the landing strip, as the grass on it is "probably sweeter" than the nearby scrub. And my favorite words of caution: "Allow enough reserve for power/rate of climb to clear the big trees in case of going around when warthogs cross the runway."

Those aren't issues that a 747 pilot will often confront, and I have to admit how excited I was by the thought that some places still exist where aviation can present challenges that legends such as Beryl Markham, Tom Black and Denys Finch Hatton would recognize.

My colleagues and I didn't have time to do any light aircraft flying during our short stay in Nairobi. But after breakfast we did visit Isak Dinesen's old farm in Nairobi, so familiar to fans of the Out of Africa movie and book, and now one of the city's most popular tourist attractions. Her old, rough farm runway is now a suburban street, we were told, and I wondered if the Ngong beacon she refers to in her book is in the same place as the one that appears on our navigation charts today (Ngong, or GV, 115.9).

All too soon it was time to leave the old farm and head back to the big airport, and to walk into the cockpit of the 747 that would return us to London---without having to stop along the way or even to check the stars. I sat down in my seat, plugged in my iPad and turned up the brightness on the cockpit screens. Before we started our checks, I paused for a moment to look out through the 747's thick windows and to think of the long history of aviation in this very special part of the world. In a very small way, I felt that I was now a part of it---or perhaps I should say that, in a very big way, it was now more than ever a part of me.

Mark Vanhoenacker is a senior first officer for British Airways who flies Boeing 747-400s. He's the author of "Skyfaring: A Journey with a Pilot." You can reach Mark at mark@skyfaring.com.

Want to read more adventures and get insights from working pilots? Check out our AirFare archive.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox