Gone With The Wind

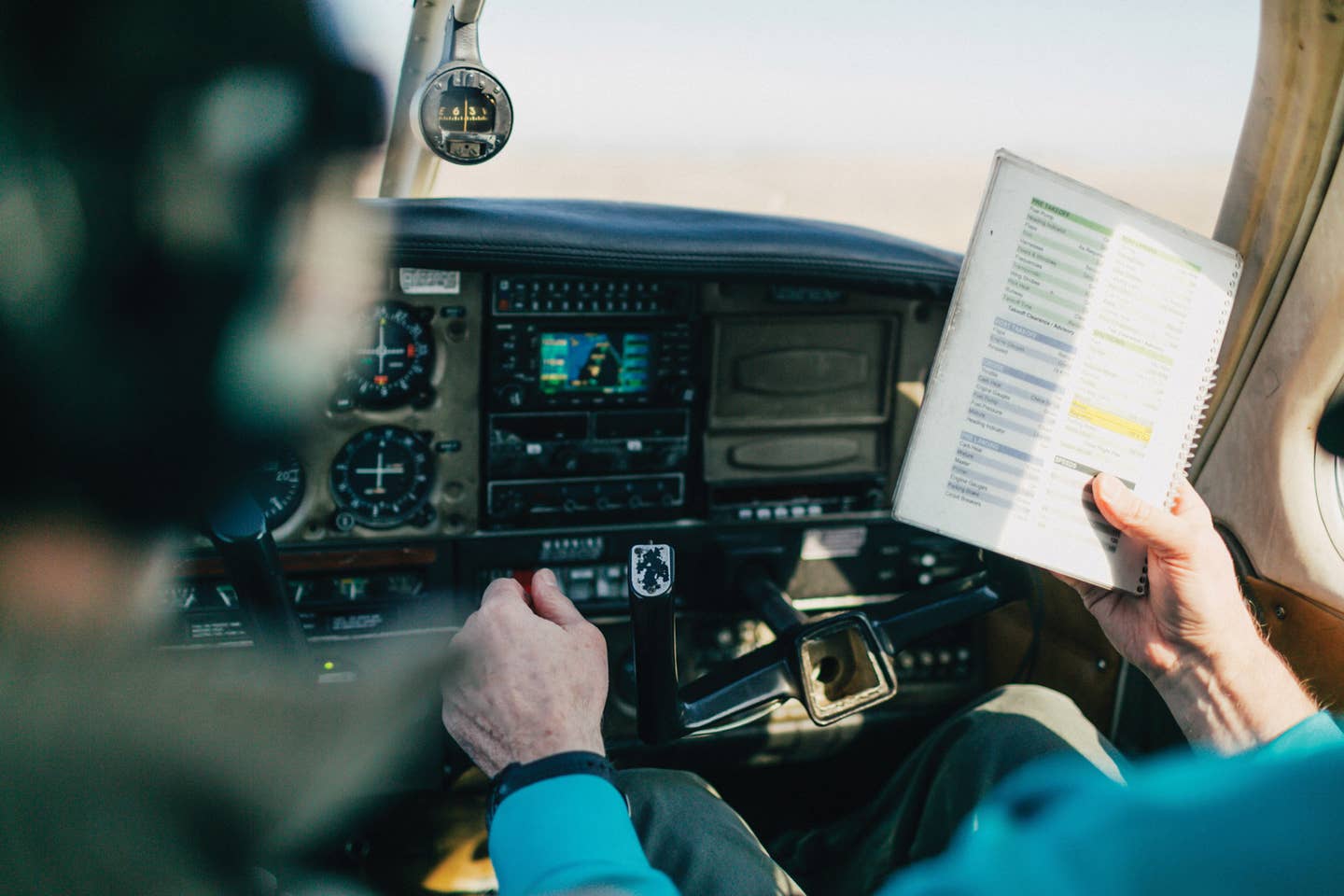

Crosswinds can be deadly, even for the most experienced pilot

With apologies to Margaret Mitchell, most pilots would welcome the opportunity to be "gone with the wind" and let Mother Nature help keep a lid on upwardly creeping fuel costs. Just a few days ago, a friend of mine found that favorable winds aloft coupled with a direct-to-destination IFR routing cut more than a half-hour off the usual trip home to New York after a business meeting in Ohio. Even better, there was an absence of shear and turbulence, making for a smooth, quick ride. Unfortunately, that's not always the case. From time to time, National Transportation Safety Board investigators have to look at situations in which the capabilities of the pilot and/or the aircraft were exceeded by wind conditions.

Cessna T-R182

On September 15, 2002, at approximately 10:35 a.m., a Cessna T-R182 crashed at Joslin Field in Twin Falls, Idaho. The aircraft collided with a fuel truck that was parked at a marshalling area on the airport. The commercial pilot had attempted a go-around following an approach to runway 12. The pilot and two passengers sustained fatal injuries as a result of the crash and post-impact explosion. Visual meteorological conditions existed and the pilot was on an active VFR flight plan. The personal Part-91 flight had originated from Kalispell, Mont., at approximately 8:00 a.m. The airplane was making a fuel stop at Twin Falls on its way to Sacramento Executive Airport.

The pilot contacted the Great Falls Automated Flight Service Station (AFSS) twice on the day before the accident, requesting weather information for the flight. At 7:03 on the morning of the accident, he contacted Great Falls AFSS again and received a weather briefing for the leg to Twin Falls and then on to Sacramento. The pilot was advised of the en-route weather, including a report of winds at Twin Falls from 170 degrees at 16 knots.

The pilot contacted the Twin Falls Air Traffic Control Tower when he was about 13 nautical miles north of the field. The tower controller advised that winds were favoring runway 12, from 150 degrees magnetic at 20 knots, and instructed the pilot to contact the tower when three miles north of the field.

About four minutes later, the pilot reported three miles north of the airport and the tower controller cleared the pilot to land on runway 12. There were no further communications to or from the aircraft.

The tower controller reported to investigators, "It appeared the pilot was having problems with the winds and was attempting to go around..." and "...that when he tried to go around, the aircraft kept going to the left...."

A line fueler with a local FBO reported seeing the aircraft in a continuously right wing-low attitude until the time of the impact with the fuel truck. He indicated that the angle of bank decreased periodically, but that the aircraft was always in a right wing-low attitude. Additionally, the fueler reported "...when it looked as if he was pulling up, he was only about five feet off the ground and about 10, 20 feet away from the fuel truck...." He also remarked that the winds on the day of the accident weren't uncommon for Twin Falls and he estimated the wind between 20 and 25 knots out of the south-southeast.

The pilot held a commercial certificate with airplane single-engine land and helicopter ratings and an instrument rating for both fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters. His second-class FAA medical was current with the restriction that he "must wear corrective lenses and possess glasses for near and interim vision."

No pilot logs were discovered or made available to the investigative team. Based upon his last Federal Aviation medical application, it was estimated that the pilot had 2,200 hours of flight time.

The manufacturer provided a "Wind Components" Chart for the Cessna T-R182. The chart had a note reading, "Maximum demonstrated crosswind velocity of 18 knots (this is not a limitation)." The 1979 Cessna T-R182 flight manual defines demonstrated crosswind velocity as "the velocity of the crosswind component for which adequate control of the airplane during takeoff and landing was actually demonstrated during certification tests. The value shown is not considered to be limiting."

Aviation surface weather observations taken at Joslin Field were reviewed by investigators. At 9:53, the wind was from 170 degrees at 20 knots, with a peak wind gust of 28 knots recorded at 9:53. At 10:53, the wind was from 180 degrees at 19 knots, gusting to 27 knots, with a peak wind gust of 30 knots from 190 degrees recorded at 10:37.

The point of impact was 231 feet perpendicular to and north-northwest of the centerline of runway 12 (155 feet outside of the boundary of the designated safety area for runway 12). The marshalling area consisted of parking for five fuel trucks, side by side, with each truck's longitudinal axis roughly parallel to the centerline of runway 12. All of the aircraft's major components were located at the crash site. There was no evidence that any flight control cables were disconnected prior to impact. The flap jackscrew was extended to a point consistent with a five-degree flap extension. The landing gear was observed in an extended condition and the elevator trim jackscrew setting was consistent with a neutral (zero degrees) trim setting. The throttle, propeller control and mixture within the remains of the instrument panel were all in the full-forward position and the control cables had separated from the engine.

The NTSB determined the probable cause of this accident was the pilot's failure to maintain runway alignment and his failure to execute a timely go-around maneuver, resulting in the aircraft impacting a parked fuel truck well clear of the runway safety area. Contributing factors were the wind conditions and the parked fuel truck.

Mooney M20R

On September 20, 2002, at 6:37 p.m., a Mooney M20R operated by a commercial pilot hit trees and caught fire during an attempted landing at the Mountain Air Country Club Airport in Burnsville, N.C., after a flight from Asheville, N.C. No flight plan was filed for the Part-91 personal flight, nor was one required. Visual meteorological conditions prevailed. The pilot and passenger received fatal injuries, and the airplane was destroyed by the post-impact fire.

The pilot received wind information from a pilot monitoring the airport UNICOM, then announced she would make a low pass over runway 14 to observe the windsocks. The pilot stated on the radio that conditions were bumpy, then announced she would attempt a landing on runway 14 and, if unsuccessful, she would return to Asheville.

Several witnesses outside on the decks of the country club and restaurant adjacent to the mountaintop runway observed the airplane make a low pass down runway 14, then enter the traffic pattern. Witnesses reported seeing the airplane on a low, flat, final approach to runway 14 with its gear and flaps down. One witness stated the airplane appeared as if it was going to land directly on the numbers, but just prior to reaching the end of the runway, it suddenly banked left and dropped down the mountainside out of view. Two other witnesses reported the airplane appeared to pitch up and bank left, then drop from view. The witnesses then heard a loud crash and observed smoke.

The pilot held a commercial certificate, with ratings for airplane single-engine land, multi-engine land and instrument airplane. The pilot's third-class medical was current with the restriction "must have available glasses for near vision." Remnants of a pilot log retrieved from the wreckage disclosed that the pilot recorded more than 2,600 hours of flight time, including approximately 250 hours of flight time in the accident airplane.

Witnesses described the wind conditions as generally from the east-southeast, with gusts from five to 15 knots, and one witness stated there was a wind gust of 10 knots from the northwest while the airplane was on final approach.

The private mountaintop airport was at an elevation of 4,436 feet. The paved surface for runway 14/32 was 2,875 feet long and 50 feet wide. Runway 14 began atop a steeply sloping terrace with an abrupt drop-off at the approach end, departure end and left side of the threshold. An Airport Information Summary card stated, "Runway 32 has an uphill incline of 46 feet. Runway 14, thus, downhill 46 feet. Recommended approach unless there is significant tailwind is runway 32." The card also stated, "High banks on right-hand side of approach ends of both runway 14 and 32, within 20 feet of edge of pavement...Mountainous terrain in area. Caution: Mountain turbulence, approach downdrafts, density altitude." Other published safety information urged pilots unfamiliar with the airport to go to Asheville in wind conditions greater than 10 knots or if winds are favoring runway 14. The pilot had flown into the airport for several years and was familiar with landing on runway 14.

The NTSB determined the probable cause of the accident was the pilot's failure to maintain airspeed during final approach, which resulted in an inadvertent stall and uncontrolled descent into trees and terrain. Factors were wind gusts and terrain-induced turbulence.

Peter Katz is editor and publisher of NTSB Reporter, an independent monthly update on aircraft accident investigations and other news concerning the National Transportation Safety Board. To subscribe, write to: NTSB Reporter, Subscription Dept., P.O. Box 831, White Plains, NY 10602-0831.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox