Dodging The Tornados

’Oh, by the way, could you drive a new T182 back from Lakeland, Fla., to Long Beach, Calif.?’

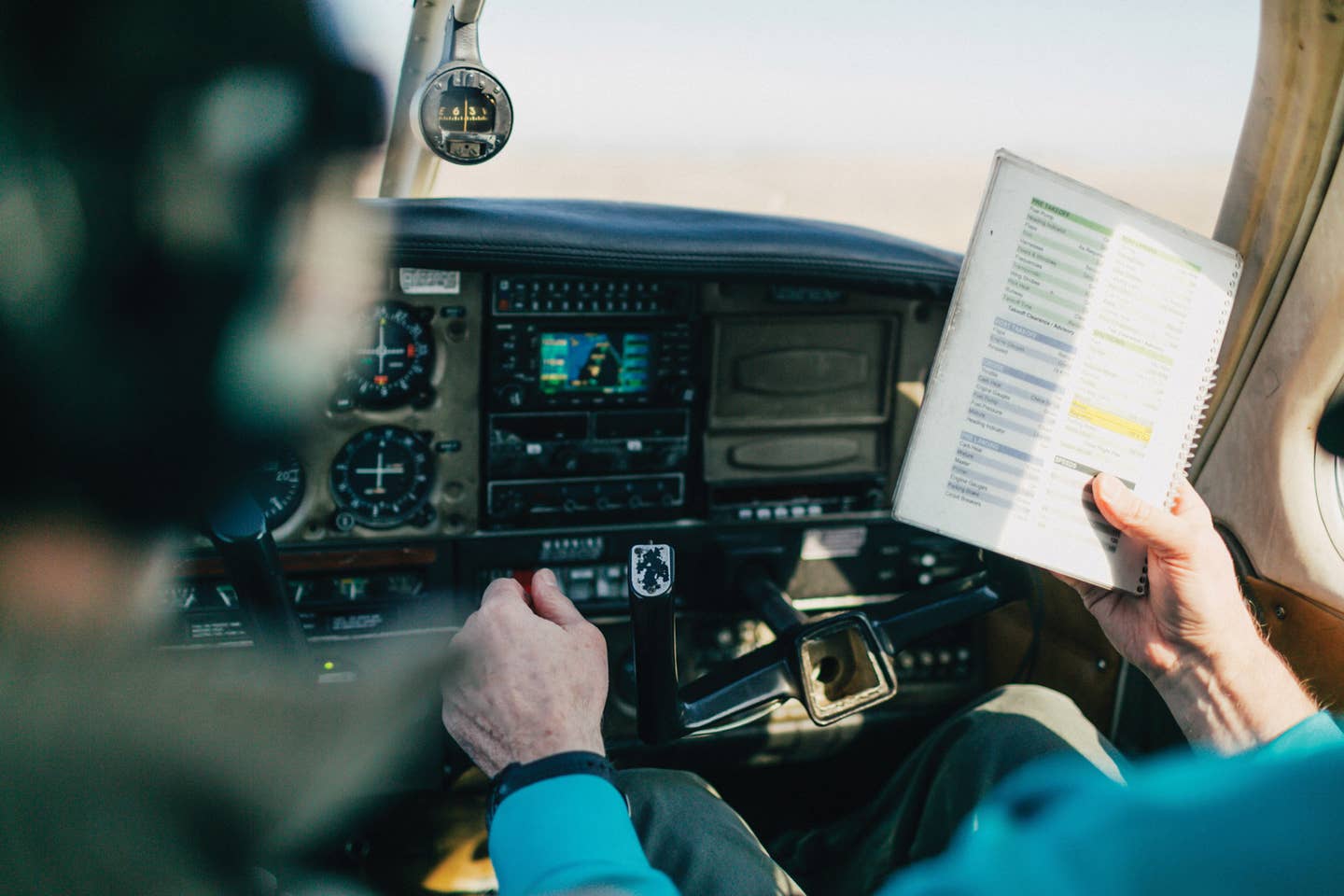

AN OLD FRIEND WITH NEW TRICKS. After an airline trip to Sun ’n Fun, Bill Cox delivered a Turbo Skylane back to Southern California. |

There are worse jobs in aviation. It was during the last two days of Sun 'n Fun 2009 that I got the call from Tom Jacobson of Tom's Aircraft in Long Beach. "Why sure," I said. "I'd be happy to deliver a new 2009 Turbo Skylane. It might even be fun."

The Sun 'n Fun show had been surprisingly upbeat, despite some inevitable scaling back by several of the exhibitors. The air show was excellent, especially the Friday night performance, the displays were well organized, and the Sun 'n Fun folks couldn't have been more friendly.

I had used mileage for my trip down and back, so returning in a new Skylane would be a pure treat, far better than a business-class seat on American, if not quite as quick. Okay, so the Skylane wasn't a Jetprop to Australia---the G1000 Skylane was still about as comfortable a piston Cessna as you could imagine.

The Garmin G1000 integrated flight display makes IFR almost silly-simple, the GFC 700 autopilot is perhaps the most sophisticated general aviation system on the market, and the airplane has the added benefit of being a 182, arguably the best of the Cessna singles.

Photographer Jim Lawrence and I had somehow crammed seven pilot reports into three busy days, everything from a Cessna Mustang jet and Piper Meridian turboprop to a Cessna T206 and a Gobosh 800 LSA. Contrary to what you might imagine, that's a lot of work, but again, not the toughest job in aviation.

Mike Barker of Air Chart System volunteered one of his full U.S.A. IFR books, plus a package of approach plates for the return flight to California. I tried to remember everything I had learned about the Garmin G1000 do-everything glass panel, and I finally launched from Lakeland around noon on April 27.

Inevitably, I got off late on my first leg west, and the winds were waiting at the top of Florida to push back at the Skylane's big McCauley prop. I knew from the preflight briefing that there were severe thunderstorms in the lower Midwest, though the forecast for my first 600 nm leg was good and actually improving as I flew farther toward Texas. I was hoping the CBs would move north and allow me some peaceful coexistence on the 1,900 nm trip west.

With no life vests or raft aboard, I'd need to forego the direct route across the Gulf of Mexico, preferring the safer flight over Cross City and along the northern Gulf beaches. I had filed for 12,000 feet above Tyndall AFB and Pensacola NAS, and settled in for a four-hour hop to Lafayette, La., hard by the Texas border and allegedly still on the east side of the weather. The late-April clouds topped at about 9,500 feet north of Lakeland, leaving me cruising in smooth, clear air and sunshine well above the chop.

As I flew northwest, however, the clouds began to climb until the tops were only 500 feet below me. Listening on JAX Center frequency, I heard everyone asking for higher except for one pilot.

"JAX Center, Saratoga 3274 Bravo at 12,000, requesting lower." Short pause, then, "Roger 74B, we'll have lower for you in about five miles." Short pause. "Yeah, the dogs are definitely not liking this altitude," said the pilot.

I couldn't resist. "Saratoga 74 Bravo. Say type dogs." Without hesitation, the pilot replied, "One chihuahua and one sheltie." Short paws.

"How can you tell they don't like the altitude?" I asked.

"They begin to pant very fast," he said. A minute or two later, JAX came back with, "74 Bravo, you and your dogs are cleared out of 12,000 for 6,000."

The forecast proved fairly accurate. As I drifted west over Gulfport and Lake Pontchartrain north of New Orleans, the clouds began to clear for my descent into Lafayette, though winds aloft were still strong on the nose. The winds were howling on the ground as well, but the approach and landing were uneventful.

Odyssey Aviation refueled my Skylane while I checked on the latest weather. The forecast wasn't good. Fifty miles ahead, the weather was atrocious and becoming more dangerous by the hour. The line of severe thunderstorms and tornado conditions now stretched practically from Galveston all the way north to Chicago, solid red returns on the computer-generated image.

The briefer at 800-WX-BRIEF verified that he had rarely seen such a classic development of tornado weather, almost a perfect storm of low pressure and thunderstorms. The weather was assaulting most of East Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri and Indiana. It was only early afternoon, but it was obvious I wasn't going any farther west that day.

The next morning, the northeast/southwest line of severe weather had slid slightly north, and the intensity was less gnarly over Houston and points west. Tornados had chewed on northeast Texas and Oklahoma during the night, but they had spared western Louisiana. I knew I'd need to deviate slightly south of a direct track to get around the southern tip of the thunderstorms, but I wasn't the only one looking for a route west.

Jennie Mitchell, Mooney's west coast regional manager, had also flown out of Lakeland the day before and been stuck in Lafayette overnight. Jennie was trying to fly a new Acclaim S home to the factory in Kerrville, Texas. We compared notes on the weather, and both agreed the smartest choice was to deviate south of Houston to avoid the meteorological misery.

Level at 12,000 one more time, I was scudding in and out of the tops, but NEXRAD painted a very different picture from the day before. Those angry red splotches had drifted out of my path, and ATC willing, I was able to assume a more-or-less direct course from over Hobby Airport to Ft. Stockton, Texas. Winds aloft had shifted out of the south, rescuing me from the direct headwinds I had been facing for the last 600 nm.

I shot the GPS approach into Ft. Stockton, refueled, attended to some biological functions and was back in the air within a half hour. As I flew across the bottom of the low, the wind shifted again to strong northerlies, a near-direct right crosswind.

El Paso drifted by below, then Las Cruces and Deming, N.M. The clouds dissipated to severe clear, fairly typical for New Mexico and Arizona in late spring. No matter how many times I fly the Southwest, I'm always impressed by the uninhabited expanses of desert, the long, straight sections of highway, the proliferation of dry lakes and all the other wonderful emergency-landing sites. It's an interesting contrast to the hundreds of square miles of houses in Los Angeles.

I dropped into Casa Grande, Ariz., one last time for fuel before lofting to 10,500 feet for the final leg to Long Beach. Finally, after 1,600 miles of head- and crosswinds, the breeze shifted to tailwinds, pushing me along at 170 knots. I watched the sun set straight ahead as I passed Palm Springs and landed at Long Beach a half hour later.

Despite the realities of tornados in East Texas, it was a day and a half of interesting flying in a perfect example of an old friend. Yes, there are worse jobs in aviation.

Bill Cox is in his third decade as a senior contributor to Plane & Pilot. He provides consulting for media, entertainment and aviation concerns worldwide. E-mail him at flybillcox@aol.com.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox