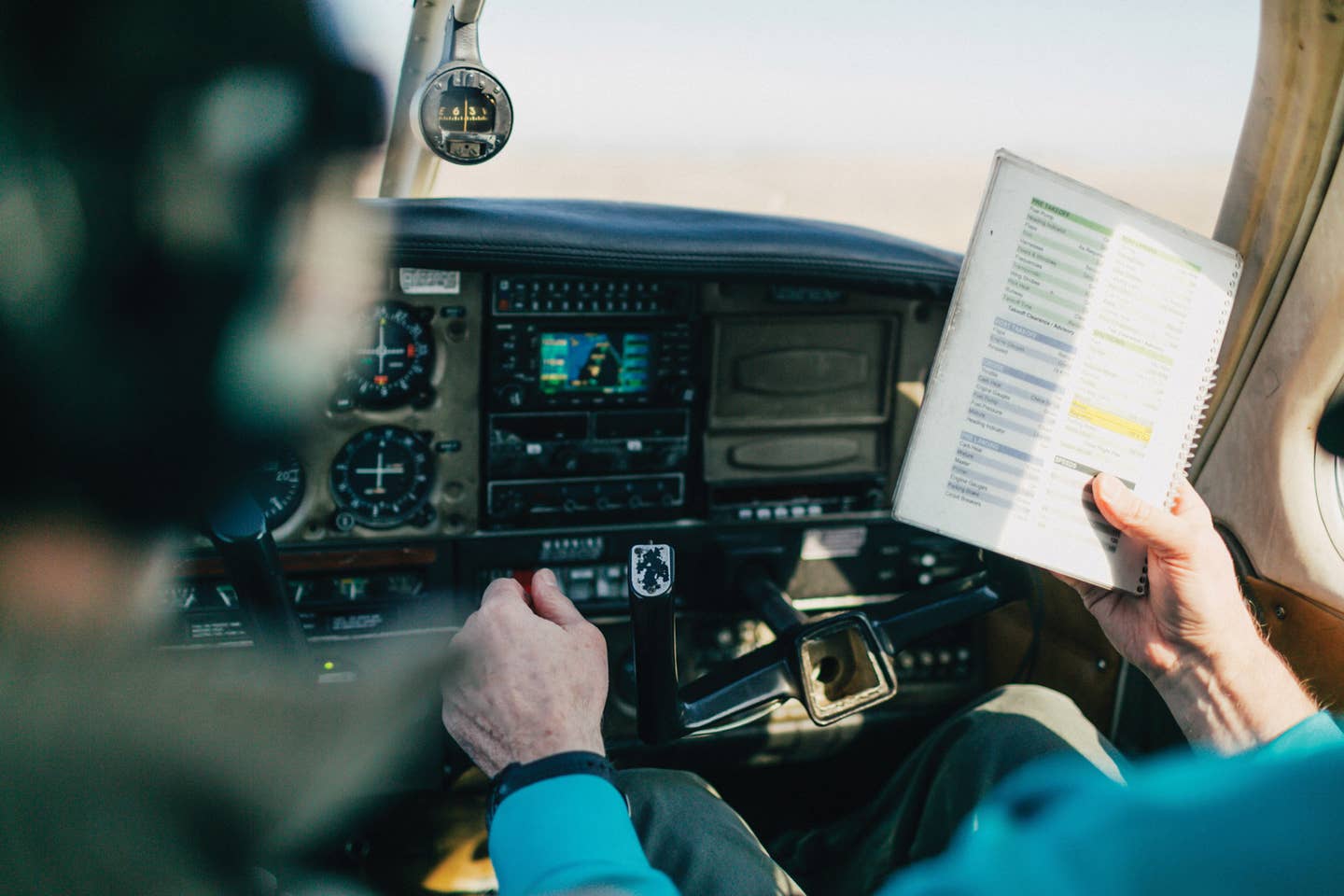

Teamwork is important in making sure that control failures don't happen. Patty Wagstaff and her crew follow a written checklist before every flight, and the most important item on it is to check for FOD in her airplane. |

The NTSB Report read: "On-scene examination determined that the airplane impacted the ground with the left wing down and a 30-degree nose-down pitch. The wreckage examination identified a loose, puck-like, 4.5-inch diameter portable XM-GPS antenna in the empennage tail space that houses the elevator bell crank. The antenna had a 9-mm diameter semicircular indentation witness mark that was consistent in shape and size to the end of a 9-mm diameter bolt that attaches the forward spar of the vertical stabilizer to the fuselage frame, located directly above the elevator bell crank. The antenna location and associated witness mark indicate that the unsecured antenna migrated to the tail section of the airplane and obstructed the free movement of the elevator bell crank, limiting the pilot's ability to control the airplane in pitch."

Control failures and foreign object damage (FOD) aren't something that GA pilots often think about. We might hear of disastrous accidents on takeoff where someone forgets to remove gust locks, but in the air show world, we think about FOD and control failure all the time. In January, the NTSB issued a new safety alert: "All Secure, All Clear (forgotten and unsecured items have jammed control system components and caused crashes)." Aerobatic airplanes are designed to be light, eliminating cockpit refinements like bulkheads, which makes it easy for stuff to get lodged in our flight controls. The careful aerobatic pilot checks for FOD in the airplane before every flight.

I didn't know the pilot in the incident above, but I probably assumed he was too low and lost situational awareness. If the NTSB hadn't found the GPS antenna, we would've never known what happened. An accident without a clear ending is the most tragic because we can't learn from it.

The first of four control failures (yes, I'm counting) I've had due to FOD was in a Super Decathlon. I had just flown 2,500 miles from Alaska to Wisconsin for an aerobatic competition, and the airplane performed beautifully. But, on my first aerobatic practice flight, when I rolled the airplane inverted, I knew immediately something was wrong. I wasn't able to move the stick forward to keep the nose up. Luckily, my ailerons were free and clear, so I was able to roll back upright. The Super D has a very responsive trim control, and I had practiced flying with trim only, maybe just for this moment, so I headed straight for the runway. After landing, I took off the rear fuselage inspection panel and voilà ! A full set of keys were wrapped around the elevator bellcrank. They belonged to a friend I had given a ride to just before I left Alaska. He got his keys back via FedEx as soon as I could dig them out of the empennage. Since then, I've never flown akro with a passenger without asking them to first empty their pockets.

Three years later, I was flying a Pitts S-1T. Akro pilots are always looking for ways to lighten their airplanes to get better performance, and I'm no exception. A few days before a contest, I removed the battery from the airplane to save a few pounds.

I arrived at the contest, registered and then took off for a practice flight in the box. I'll never forget the tailslide I executed: The airplane went straight up, the power came off, and I slid backwards and flopped forward to a perfect vertical downline, perfect except that I wasn't able to pull out of it. Something was jamming the elevator control. This wasn't my first rodeo, and I quickly used the Pitts' powerful trim handle to level the airplane off, enter the pattern and make a very careful landing. I looked in the tail and a rather large piece of wood jamming the controls. It was the battery tray. When I removed the battery, I didn't realize the tray the battery rested on wasn't fixed to the steel tube fuselage.

Since then, I've been very careful with my preflights. I follow a written checklist religiously before every flight, and perhaps the most important item on it is to check the airplane over carefully for FOD. There's a reason why every Extra manufactured has a clear Lexan panel on the lower-right rear fuselage of the airplane, because that's where everything that doesn't belong in the airplane---keys, earrings, passports, wooden battery trays, tools---ends up.

As the saying goes, you can never be too careful, and yet things can still happen. The third time I almost had a really bad day was when I was flying the Extra 260 at an air show. The morning of the show, I had some avionics work done to repair a bad radio. As showtime loomed, I was very anxious to get in the air and kept bugging (in a nice way, of course) the avionics guy, who was working as fast as he could, to get the job finished. As soon as he zipped up the cowling, I jumped in the Extra and took off for my first flight. To show off the great performance of the 260, my opening maneuver was a Vertical S---a double climbing half-loop. When I got to the top about ready to push over to go downhill, something in the stick didn't feel right. The elevator wasn't completely jammed, but I felt something restricting smooth control movement. I didn't know what the problem was, but I sure wasn't going to troubleshoot it in the air when I was over a perfectly good runway.

My crew came running over to see what was wrong. Clear as day, inside the Lexan panel, we saw one, two, three---there were nine---small screwdrivers and a plastic case. You might say I was horrified to think about all that stuff floating around in the tail of my airplane. It was creepy to think that even with a careful preflight, I didn't see the screwdriver case left on top of a radio stack before takeoff.

FOD doesn't have to be wood or steel. A friend of mine told me he did a roll on takeoff at an air show, and a sectional chart smacked him in the face, temporary blinding him a few feet off the ground.

My fourth---and hopefully my last---control failure happened when I was practicing near an airport outside of Tucson. I remember it well. It was late in the day, there was a high overcast, and the flat light made the runway seem much farther away than two miles from the box.

I had no idea what had caused the elevator to jam and didn't want to make the situation worse, so I set the trim and headed for the runway. I had to set a level descent to the runway without letting the descent rate get too steep. The Extra is unstable, and I found it difficult to set a level attitude because the airplane wanted to diverge into a climb or descent. Also, my trim control was stiffer than in previous airplanes, making it harder to fine-tune. It wasn't a great situation. I got the airplane on the ground, and while rolling out, noticed that my hands were shaking.

I had a tank for smoke oil behind my seat, and the fuel cap was nonstandard for an Extra. It was the type that had you turn a handle to tighten the seal. In the weeks prior, I noticed the cap was losing its seal and was getting harder to tighten, and I had planned to replace it at annual. I purposely put a small metal chain on it to the tank in case it came off during flight---an attempt at eliminating FOD problems. When I was up doing akro, the cap came off, the chain held it, but it lodged between the tank and the torque tube, completely jamming my elevator control.

What did I do wrong? In each case, I admit I was really lucky. I made mistakes, but I did some things right, too. I dealt with each situation methodically. I didn't try to troubleshoot in the air. My primary mission was to keep flying the airplane and get it safely on the ground. I didn't bother with a lot of radio chatter. Also, I had practiced flying with trim only and made sure my trim controls were smooth and responsive.

Mistakes? I didn't ask my passenger if his pockets were empty before we did aerobatics. I also second-guessed the battery tray and didn't remove it with the battery in the Pitts incident; I didn't listen to warning signs with the loose fuel cap in the Extra and was waiting for the annual to get it replaced; I rushed the avionics technician and didn't watch when he replaced the cowl to check for loose items.

A full set of keys were wrapped around the

elevator bellcrank.

The worst thing about a control failure in an airplane is a loss of faith. Instead of being your friend, the aerobatic airplane that you wear and not just fly becomes the wolf that bites the hand that feeds it. A friend of mine had the stick in his aerobatic airplane break off during flight. He was able to land it safely and told me later that the first thing he thought when it happened was how much this would affect his confidence and trust in the equipment later.

The loss of faith is a test. We fix the problem and need to move on to restore our confidence. Get back on the horse that bucked us off. When I'm flying an air show, I need to trust my airplane and have confidence in it.

I'm not telling these stories to make some sort of emotional confession. They taught me something, and if I pass them on, they might help you avoid the same mistakes. In all likelihood, you'll never have these situations happen in your Cessna or Piper, but I'd suggest keeping a sterile cockpit and checking inside the airplane for loose tools and parts after annual but before your mechanic zips it up.

We don't have to be air show pilots to know what we need to have confidence in the machines we fly. We're all capable of making mistakes, but solid preflights, good preventive maintenance, keeping a sterile cockpit, not waiting until annual to fix or repair things, staying current and practicing flying with trim all help give confidence and trust, and enable us not only to be safe, but allow us to get maximum pleasure and enjoyment out of our flying. Isn't that what it's really about?

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox