The text comes from an unknown number. “Do you own a Taylorcraft? A yellow one?”

I find myself staring at the phone in disbelief. What stupid airplane antics have I recently participated in that would warrant the query? To the best of my knowledge, none. A blossoming sense of anger drives my thumbs.

“Who is this and why do you want to know?”

Then comes the reply: “Oh, sorry. My name is Andrew, and I used to fly that airplane in the early 2000s. I was just curious if it’s still being flown so I looked it up in the FAA database and it listed you as the owner. Do you still fly it?”

Anger easing. “Yes, I do. It’s a great airplane.” My attitude transforms from a bit anxious to really curious. Instead of another text message, I call Andrew.

Our entries into aviation were very similar. Both of us had neighbors who owned airplanes and took us flying when we were not yet teens. Andrew flew with Bill, a previous owner of the Taylorcraft. My aviation mentor was John, owner of a Cessna Skylane.

On the call he asks: “Do you have any pictures?”

Do I? Photographs of the T-craft are more readily available than pictures of my children. A few swipes and a tap later sends the latest pics.

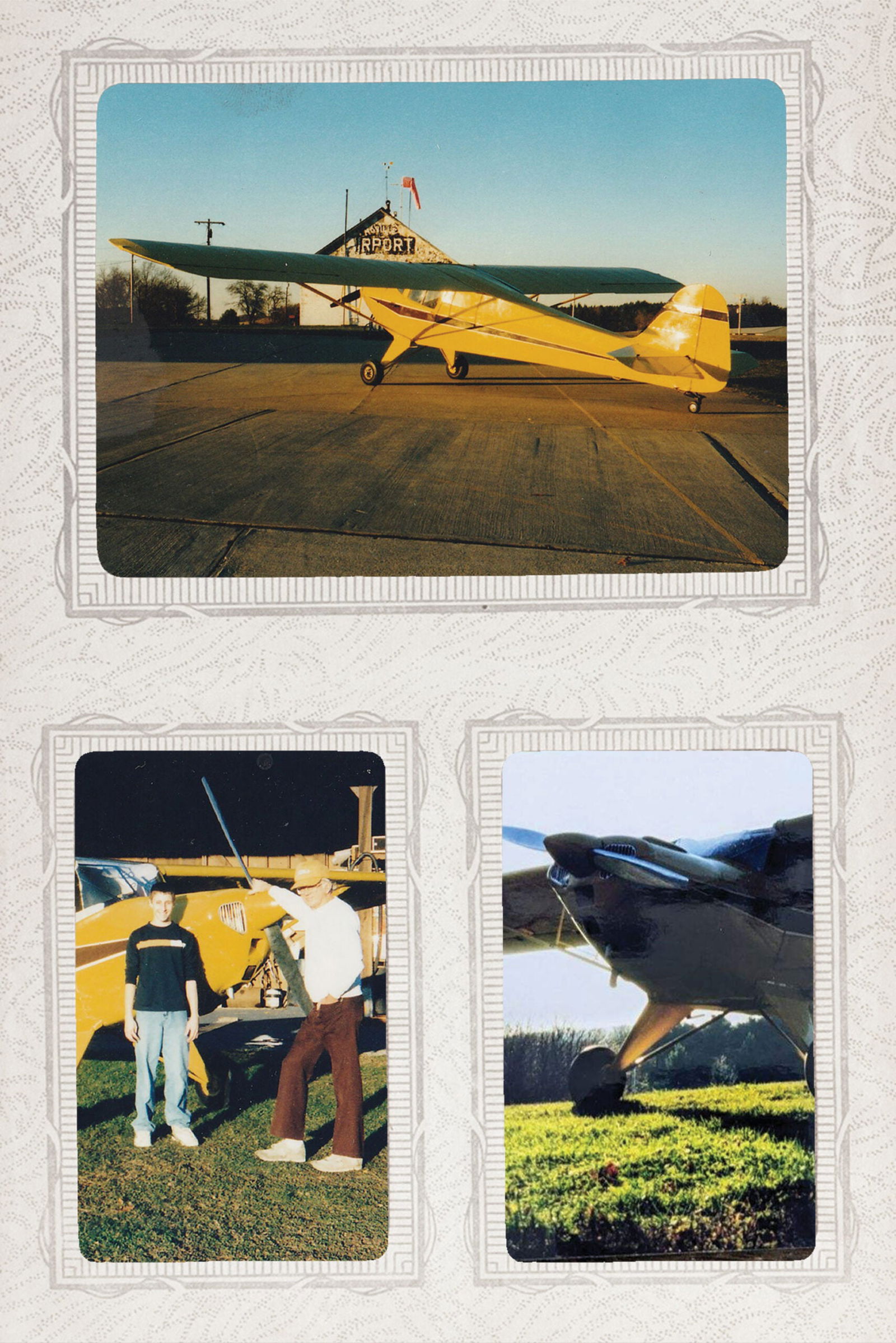

Andrew replies with a few photos of the airplane taken more than 20 years ago. The familiar yellow Taylorcraft is parked by a galvanized corrugated steel roof shed-style hangar. “Had you not sent me that pic, I’d swear it was taken at Post Mills [in Vermont].”

“How often do you fly her? Does anyone go with you?”

“We fly as much as we can. My entire family likes to go. When they can’t join me, I really enjoy giving people rides. Some flights are sightseeing. Others we might fly 15 miles south to Lebanon, New Hampshire, grab a crew car and get takeout, buy beer, or go to the hardware store. We use the airplane like a car whenever possible.”

Andrew laughs. “Man, that’s exactly how Bill used her, too. We’d fly 10 minutes to the next airport to have coffee or pick up a magazine. Any excuse. It’s like the airplane found you and its happy place again.”

Over the next few weeks, we exchange photos, updates, and stories of adventures with the Taylorcraft. Keeping in touch with Andrew becomes an enjoyable part of my aviation experience.

The landing gear was damaged while flying on skis. With the airplane up on blocks and tied down in the hangar, I sent Andrew a photo. “Looks good with retracts,” he replies. In addition to repairing the left gear leg, the right gear and rudder were removed for recovering.

An exact color match wasn’t possible and my son Nathan thought checkerboard might look nice. The alternating brown and yellow might confuse the eye just enough to mitigate the mismatch. It worked pretty well. Along with the photo of the new look, I also had a request. “Can we fly out to Butler at some point and take you for a ride?”

Andrew and I chose to meet at Pittsburgh-Butler Regional Airport (KBTP), 455 miles or about five hours of flight time from the home base of Post Mills Airport (2B9).

Coordinating schedules and weather took almost six months. With 18 gallons of fuel on board burning 4.5 gph, the trip could be made with one stop each way. Even in the T-craft, fuel endurance greatly surpasses biological endurance. Adding an extra stop in each direction ensures there are no stresses of the liquid kind to be had. The first leg was 176 miles to Albert Nader Regional Airport (N66) near Laurens, New York, to stop for gas.

Somewhere near the Pennsylvania border with New York, the farming practices change from planting a single crop uniformly across the field to contoured intercropping. The practice of tilling along contour lines and alternating between multiple crops is said to reduce soil erosion and maintain soil health. From the air, the swirling lines of different crops are very interesting to see and a great indicator of slope direction in the event of an off-airport landing.

Years of flying sailplanes cross-country has me on the constant watch for land-out options. The route ahead is mostly trees. Remaining in contact with river valleys and open fields feels prudent. Taking the circuitous route adds just 10 minutes but makes for a significantly more relaxing flight.

Having flown many Piper aircraft, with a good bit of time in the J-3, it felt appropriate to stop for a pit stop at Piper Memorial Airport (KLHV) in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania. Early afternoon with still about 120 miles to go, the Piper museum can wait for another excuse to fly. Next stop, Butler. Total flight time came to six hours.

After securing the T-craft on the ramp and walking to the FBO, a shout grabs my attention. “Hey, Kevin. It’s me, Andrew.” We meet inside the door and exchange stories about the flight. “I can’t believe you made the trip,” he says.

Kevin and Andrew today. Reuniting a favored passenger is worth a full day of flying. Every single time.

“Want to go for a flight?”

“Yes. Definitely.”

Walking across the ramp, I half expect the movie plot twist where the airplane becomes animated and runs over to see the long separated friend. In truth, it did feel a bit like reuniting an old dog with the neighborhood kid who used to play together after school. Andrew’s eyes and smile were growing big as we approached the plane in silence.

“This is crazy,” says Andrew, repeating it several times. “Aside from the checkerboard paint job, she’s the same. Still have ‘Raggmop’ on the door.” He laughs. “Bill would love this.”

“Do you know what that is? More people ask me about that name than anything else.”

“I do,” Andrew says with a nod. “Bill was a pilot for Eastern Airlines and he wore a toupee. He had several of them, and one was all beaten up, and that’s the one he wore when working on the airplane. He joked it was his mop-top. There are rag wings on the T-craft, so he combined everything and painted it onto the door.”

Climbing into a Taylorcraft is anything but graceful. The family joke is that entry improves to awkward after 50 or 60 tries. Andrew’s muscle memory of his youth was fantastic. In one smooth action he glides into the right seat. “Man. This is crazy. I never thought I’d see this airplane again, much less fly it. Crazy is an understatement.”

Without an electrical system, starting the Continental A-65 is hand prop only. The engine comes to life after throwing the first blade. The ramp is empty, so I ask if he’d like to taxi us to the departure end of the runway. “No. I just want to take this all in.”

With a slight headwind the Taylorcraft breaks ground after a 400-foot ground roll and is climbing at almost 500 fpm. Apparently, the old dog has a case of the zooms and is enjoying the reunion, too.

At 2,000 feet, Andrew takes the controls. “Where shall we go?” he asks. “Wherever you like. We have a few hours of gas on board and a credit card so enjoy yourself.”

We circle Andrew’s house and waggle the wings to his family standing in the front yard waving back at us. “I’ll take you to the old airport where Bill kept the airplane. It’s a housing development now.”

The main road between the houses is the old runway. One of the hangars still stands out of line with the modern homes. “The hangar where this airplane was kept is about where the yellow house with the red car in the driveway is now. The guy with that hangar [he points to the shabby brown shed] kept a helicopter in it. Not sure if he flies anymore.”

For the next hour we fly around the area experiencing the joy of flight, wandering a bit aimlessly. Andrew gives me a tour of the area. Each change of direction is smoother and more coordinated as he reacquaints with his old friend. I take the controls right before turning onto the base leg and manage to make soft contact with the runway without excessive swerving during the rollout.

Andrew rotates the mag switch to the off position. The propeller stops moving, and the only sound is the vacuum-driven gyro inside the turn and bank indicator spooling down. After a few breaths Andrew breaks the silence. “That sound is the same. So cool and it takes forever to go away.”

We hop out of the cockpit, and Andrew ties the ship to the tarmac for the night. I replace the pitot cover and remove the wire on a cork fuel gauge, replacing it with a vented cap. The low sun and warm light smooth out the faded yellow-and-brown checkerboard, giving the airplane a more youthful appearance. We take a few pictures, and Andrew gives the ship a gentle rub on the cowling. The touch is affectionate. “Thanks.”

I wasn’t sure if he was speaking to me or the airplane.

It really didn’t matter.